SAN DIEGO (JTA) – In a darkened room at the San Diego Convention Center last week, nearly 1,000 people clapped, sang and danced to evening prayers, with the words projected on two large screens against a bucolic backdrop of mountain vistas and rolling streams.

Featuring a five-piece band, a small vocal ensemble and a charismatic, storytelling leader, the weekday evening service could have been held at any of the growing number of mega-churches in America.

But the service was in Hebrew, the prayers were lifted from the new Mishkan T’filah siddur and the participants were delegates to the Union for Reform Judaism’s biennial convention Dec. 12-16.

Ideas borrowed from evangelical mega-churches were in abundance at the five-day biennial, a trend championed by Ron Wolfson, co-founder of Synagogue 3000, a Los Angeles-based organization dedicated to synagogue revitalization.

For more than a decade Wolfson has been studying the success of Saddleback Church in Orange County, Calif., and has developed a close bond with its pastor, Rick Warren.

“Where do you think we got the idea?” Wolfson said of the service.

In the 19th century, the architects of Reform Judaism, seeking a more enlightened, rational and modern style of worship, borrowed heavily from their Protestant neighbors. They held weekly services on Sunday, cloaked rabbis in long black robes and worshiped in a high-cathedral style.

While the movement today is increasingly embracing Jewish traditions it once shunned, Reform leaders insist they must remain open to innovation. And again they are finding inspiration in Christian churches, the most successful of which hold boisterous music-driven services, expertly utilize new technologies and offer a warm and welcoming atmosphere.

“If the mega-churches can do it, maybe it’ll work for us,” said one member of Temple Holy Blossom, a large Reform congregation in Toronto. “I’m open to anything. As long as Jews are praying, I’m happy.”

With an estimated 1.5 million members spread over nearly 900 congregations, several of which boast membership rolls running into the thousands, Reform Judaism doesn’t quite reach Saddleback proportions, but it doesn’t lack for adherents either.

Less trumpeted, however, is the movement’s struggle to retain its members. Congregations frequently report a precipitous decline in membership after a child’s bar mitzvah, when both the child and the family often drop out of synagogue life.

“The most pressing challenge for congregations is attracting and retaining members,” Peter Weidhorn, the incoming chairman of the URJ’s board of trustees, told the biennial Sunday.

Weidhorn cited a recent study showing that the movement’s congregations are not as welcoming as many Reform Jews believe them to be.

Participants throughout the biennial were encouraged repeatedly to be more welcoming of newcomers to their communities in a manner that has become a hallmark of the mega-church phenomenon.

At Saddleback, first-timers are directed to park their cars in a designated area, where they are greeted by ushers and escorted to their seats. Several Reform congregational leaders told JTA they have already replaced synagogue ushers with “greeters” who perform a similar function.

“They understand how to welcome people, engage people, induct people into the life of the community,” Wolfson said of the mega-churches. “Our people don’t have a sense of mission.”

Another idea Wolfson poached from mega-churches is the idea that “congregations of relationships” must replace service-oriented synagogues in which dues entitle members to bar mitzvah their children and consult occasionally with a rabbi.

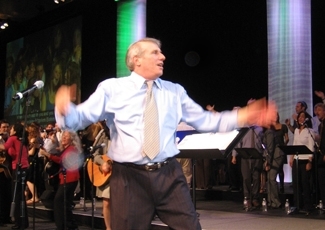

The mega-church influence was felt as well during Friday night prayers, where 6,000 worshipers gathered in a cavernous room on the convention center’s ground floor for a choreographed production of sight and sound.

Multiple cameras projected the service on several enormous screens suspended over the hall. A live band buoyed a service that was conducted almost entirely in song.

And then there’s the music, which found its way not only into the services, but into nearly every aspect of the biennial. A stage outside the main auditorium played host to a steady stream of performers. The Shabbat evening sing-along, a biennial highlight, had thousands singing and dancing in the aisles. On Saturday night, the URJ honored Debbie Friedman, the movement’s leading composer.

“It’s all about the music,” Wolfson said. “I’ve said to cantors, the cantors are absolutely critical in this revolution.”

At an evening plenary session on Dec. 13, Warren, the best-selling author of “The Purpose Driven Life” and perhaps the best-known mega-church pastor in the country, discussed how he grew Saddleback so large that he expects 42,000 worshipers to attend his 14 Christmas services next week.

Two years ago, for the church’s 25th anniversary, Warren wanted to address his entire flock together – so he rented out Anaheim Stadium.

“One of the keys to building your congregations is just to be nice to people,” Warren told the mesmerized audience. “Smile. People have a longing for belonging.”

Wolfson, a professor of education at the American Jewish University, formerly the University of Judaism in Los Angeles, and the author of “The Spirituality of Welcoming,” first attended services at Saddleback 12 years ago with his wife. He has returned many times, bringing along Reform movement leaders and rabbinical students to learn what makes the church so successful.

“Our theology is totally different,” Wolfson said. “But there’s so much we can learn about building sacred community, a deeper relationship with people.”

Lessons drawn from the experience of mega-churches extend beyond the need to be welcoming.

Reform leaders are increasingly stressing the need to provide individuals a personal sense of divine mission and have recognized the need to forge smaller sub-communities within synagogues that have grown too large to foster a sense of intimacy and belonging.

They are also looking to new technologies, such as the video screens, to enhance the prayer experience in their synagogues.

Rabbi Billy Dreskin, a congregational rabbi in White Plains, N.Y., and the leader of the biennial’s first mega-church style service, is considered a movement pioneer in this area. His workshop on the use of technology in worship drew 200 participants.

“It’s about to take off,” Dreskin said of the new worship style. “People want vibrancy in their worship, and the vibrancy can come aurally and the vibrancy can come visually.”

Not everyone enjoyed the mega-church trend. One URJ staffer told JTA she was put off by musical styles that she felt were more suited to a nightclub.

“I half expected the rabbi to say, ‘I’m Judy Shanks and I’ll be here all week,’ ‘” she said, referring to the rabbi who led Shabbat morning services.

But the overwhelming sentiment at the biennial was that the services were powerful and inspiring. Dreskin said he was surprised at how little resistance he found to mega-church techniques.

“I haven’t heard anyone here question it except me,” Dreskin said, “and I’m it’s biggest proponent.”

(JTA correspondent Sue Fishkoff contributed to this report.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.