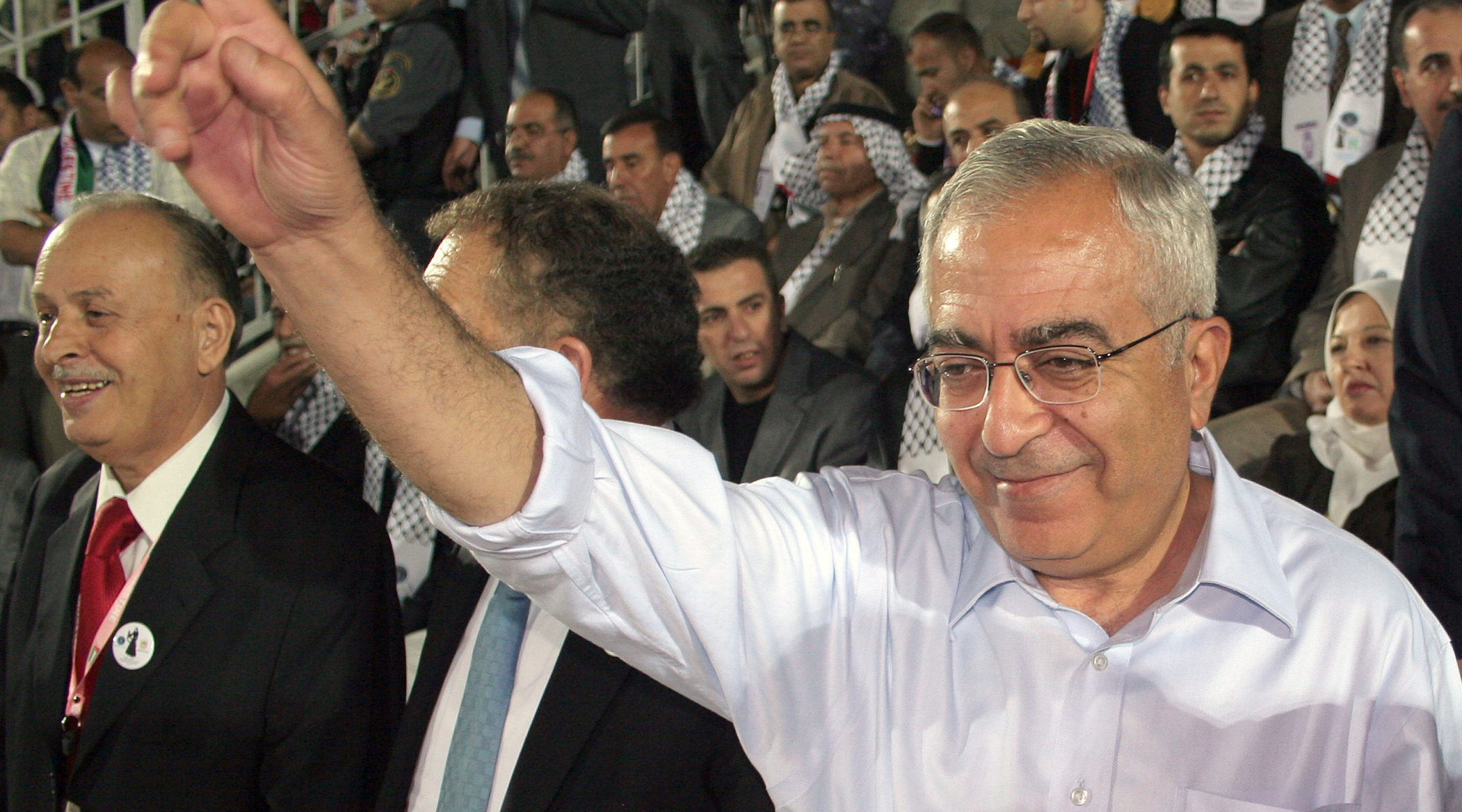

JERUSALEM (JTA) — Pundits and politicians have taken recently to comparing Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salam Fayyad to Israel’s founding father, David Ben-Gurion.

No less a figure than President Shimon Peres, one of Ben-Gurion’s foremost disciples, is the latest Israeli leader to offer the accolade.

The reason is simple: Like Ben-Gurion, Fayyad is building institutions of statehood.

In the 1920s, the Jews of Palestine under the single-minded Ben-Gurion established institutions for what they called the state-in-the-making: the Haganah with the idea of a single armed force; the Histadrut Trade Union, with a department for workers’ rights, a sick fund, a bank and the Solel Boneh construction company; and the Jewish Agency dealing with immigration, schools and hospitals.

Now Fayyad is doing something similar.

Last August he announced what has come to be known as the “Fayyad Plan” under the heading: “Palestine — Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State.” The idea is to build a de facto Palestinian state by mid-2011, with functioning government and municipal offices, police forces, a central bank, stock market, schools, hospitals, community centers, etc. Fayyad’s watchword is transparency, and his aim is institutions that are corruption-free and provide an array of modern government services.

Then, in mid-2011, with all the trappings of statehood in place, he intends to make his political move: Invite Israel to recognize the well-functioning Palestinian state and withdraw from territories it still occupies, or be forced to do so by the pressure of international opinion.

In February, at the 10th Herzliya Conference, an annual forum on Israel’s national security attended by top decision-makers and academics, Fayyad, the lone Palestinian, gave an articulate off-the-cuff address, leaving little doubt as to what he has in mind.

“This is not about declaring a state. It is about getting ready for one,” he explained. “The program we have embarked upon was not supposed to be in lieu of a political process. It was supposed to reinforce it.”

“The political process track,” Fayyad added later, “is absolutely necessary because that is what is going to bring an end to the occupation.”

Fayyad went on to speak about creating a critical mass of positive change on the ground that by mid-2011 would persuade the world that the Palestinians were ready for statehood, and that it was time for the Israeli occupation to be rolled back.

“If by then we succeed, as I hope we will,” he declared, “it’s not going to be too difficult for people looking at it from any corner of the world to conclude that indeed the Palestinians do have something that looks like a well-functioning state in just about every facet of activity, and the only anomalous thing at the time would be that occupation which everyone agrees should end.”

Fayyad has been working closely on the economic and institutional elements of his plan with Tony Blair, the former British prime minister and the international Quartet’s special representative to the Middle East, and on the law enforcement aspects with U.S. Gen. Keith Dayton.

The results on the ground have been impressive.

Palestinian security forces trained by Dayton’s troops have been deployed in West Bank cities, creating new levels of law and order and enabling Israel to remove dozens of roadblocks and checkpoints. The aim from the outset was to secure a major principle of modern statehood: a single armed force, subordinate to the elected government, with no rival militias roaming the streets. For all intents and purposes, this is the case already in the West Bank today.

At the Herzliya Conference, Fayyad suggested that Israel could help further augment this facet of his state-building by handing over more West Bank territory to Palestinian security control.

The law and order and the opening up of the West Bank to free movement of people and goods has led to a dramatic change in the economic climate, which also augurs well for Fayyad’s state-building project. The upturn in trade, tourism and consumer spending was reflected in economic growth of 7 percent last year, one of the highest figures anywhere in the world. Fayyad also is working on Palestinian budgetary independence. More than half of this year’s Palestinian Authority budget of approximately $3 billion will be raised in taxes.

There have been significant institutional achievements as well: A functioning stock market is operating in Nablus, Fayyad has been building government and municipal offices, and the nucleus of a central bank is in place.

Over the past two years, Fayyad has completed more than 1,000 communal projects, investing more than $100 million in schools, clinics, libraries and community centers. He is starting work now on a new phase to improve existing infrastructures: roads, electricity, water and sewage. Most of the money has come from the United States, the European Union and the oil-rich Gulf States.

The American-educated Fayyad, 58, was born in the village of Dir Rasun near the West Bank city of Tulkarm. After earning his doctorate in economics at the University of Texas in 1986, he conducted research at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis before joining the World Bank in Washington, where he worked from 1987 to 1995. Then, in the wake of the Oslo agreements, he was appointed International Monetary Fund representative in the Palestinian territories from 1995 to 2001.

The following year, desperate for a modicum of transparency in funding for the Palestinians, the United States and other donor nations forced his appointment on Yasser Arafat as the Palestinian leader’s technocrat finance minister. Fayyad, a small but very determined and self-confident man, bravely took on the corruption rife in Palestinian affairs, sacking thousands of superfluous bureaucrats and closing down social institutions serving as fronts for terrorist activities.

Unlike most of his generation of Palestinians leaders, Fayyad never joined the Palestinian resistance, never took part in terror and never spent a single day in an Israeli prison. This accounts for the fact that despite his internationally acclaimed success, he has only a small domestic political base. He never joined the West Bank’s ruling Fatah party, and when he ran in the 2006 elections, the Third Way party he founded, dedicated to fighting corruption, won only two seats.

A recent survey by leading Palestinian pollster Khalil Shikaki showed that although 40 percent of Palestinians rated the Fayyad government’s performance as good or very good, only 13 percent supported him as prime minister.

Fayyad was appointed prime minister by Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in June 2007 after the Hamas takeover of Gaza, and was reappointed last March. Fayyad also has been serving a second term as finance minister since March 2007.

Israelis on the right side of the political spectrum, who oppose Fayyad’s state-building project, argue that he is not as dedicated to nonviolence as he claims. They point to his presence at ceremonies honoring Palestinian terrorists and his active participation in a ceremonial burning of Israeli products manufactured in the West Bank.

Fayyad has his critics on the Palestinian side, too, who accuse his police of being nothing more than subcontractors for the Israeli occupation. Rather than bringing the occupation to an end, the critics argue, Fayyad’s scrupulous maintenance of law and order is prolonging it.

At Fayyad’s address to the Herzliya Conference, among the interested spectators was Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak. As the leader of the Labor Party, Barak is Ben-Gurion’s heir and, like Fayyad, is a strong advocate of the two-state solution.

For people like Barak, who see this as the key to a secure Jewish-majority state at peace with its neighbors, Fayyad could well be the man of the hour. And he also could prove the toughest opponent of those Israelis who see in an independent Palestine a recipe for disaster.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.