(JTA) — Soon after the Lebanon War began in June 1982, Avigdor Chen’s tank unit fell into a trap. Artillery rained from high ground occupied by the Syrians near the village of Sultan Yacoub. The battle continued all night.

When dawn broke, Chen saw a struck Israeli tank some 100 yards away. With smoke billowing from it, the tank rolled downhill. Chen ran toward the now-stopped tank. He smelled burning human flesh and looked inside. The commander, Zohar Lipschitz, was dead. Chen ventured no further into the tank, knowing that another shell could follow imminently.

Chen later learned that Yehuda Katz also had been inside the tank.

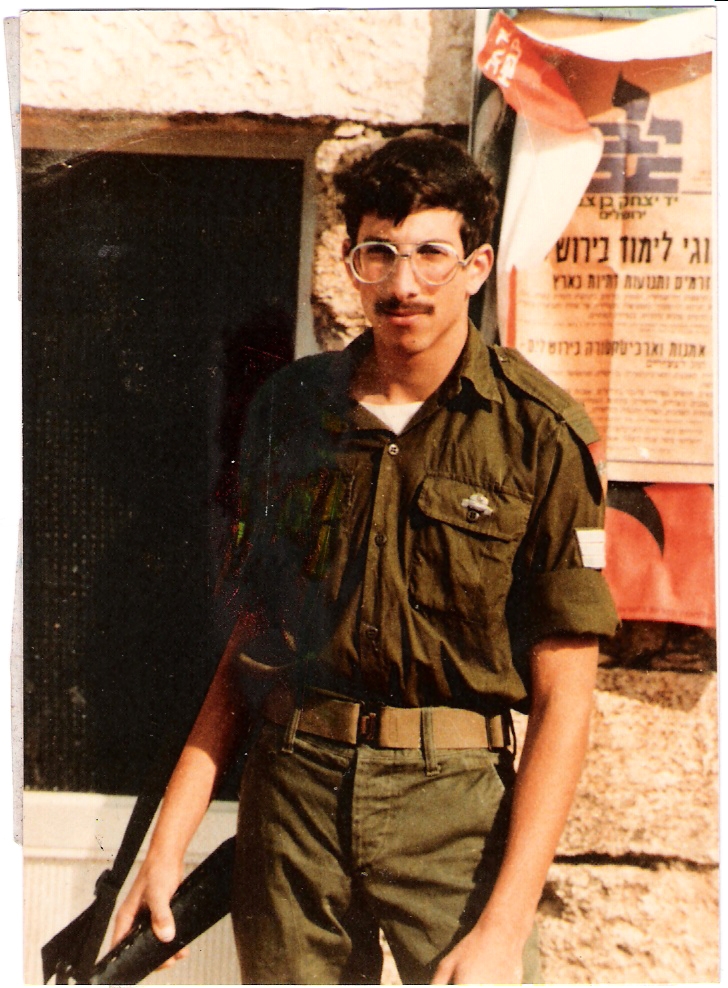

Katz, then 25; Zachary Baumel, 21, with whom Chen had been friends since basic training; and a third soldier, Zvi Feldman, 22, have been missing ever since that battle, which took place 30 years ago, on June 11. Not a single letter, photograph, video clip or third-party message from them has reached the outside world, nor has any proof emerged to indicate their deaths.

“I really feel strongly that there may be a chance that some of these guys are still alive and that there’s still hope,” Chen said. “People in Vietnam went missing for so many years and they turned up.”

But, he added, “They’re on the radar much less than they used to be. There’s not even a blurb about them.”

With Gilad Shalit’s October release from more than five years in Hamas captivity in Gaza, Israeli MIAs fell from public consciousness. Long before Shalit’s release, Baumel, Katz and Feldman were all but forgotten, unreported in negotiations over prisoner exchanges. No leftover, Shalit-era demonstrations are being recycled or protest tents filled to demand the trio’s freedom or proof of their fate.

The Israeli media recently began marking the Lebanon War’s 30th anniversary. In one radio interview, a brigade commander mentioned the missing trio in passing — but not by name.

The silence is striking for a country that values memory so highly and takes such pride in its soldiers. Within days of the 2006 seizing of Shalit by Hamas and the kidnapping of Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev by Hezbollah, posters and placards proclaiming “Return Our Sons to Their Borders” adorned Israel’s lampposts. Two summers later, the country fairly stopped in its tracks to watch television coverage of the bodies of Goldwasser and Regev being repatriated at the Rosh Hanikra border crossing in a prisoner swap.

The longer Shalit remained in captivity, the more intense became the public relations campaign by Israelis to press Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to secure his release.

Meanwhile, Ron Arad, held prisoner since bailing out from his shot-down combat fighter over Lebanon in 1986, remains a household name.

“That was a bit telling: that people didn’t put these three soldiers in the same place they put Ron Arad, Shalit and [Goldwasser and Regev],” Arieh O’Sullivan, a veteran writer on Israeli military affairs, remarked about the radio interview. “These three never had a public outcry to get them back because the military never had a public outcry to get them back.”

“They’ve been forgotten,” said Efraim Inbar, director of Bar-Ilan University’s Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. “They disappeared, as if the ground swallowed them up.”

Explanations abound for the societal distinctions: The public presumed the three soldiers dead almost from their moment of capture; the 2009 death of Baumel’s father, Yona, sapped the movement of its most vocal advocate; the Sultan Yacoub MIAs were single, while Arad’s wife and baby daughter lent powerful poignancy to everyone’s nightmare of a soldier disappearing; people and their causes move on.

Israeli governments and the Israel Defense Forces erred critically in failing to demonstrate to Israelis early on that it had overturned every stone to ascertain the trio’s fate, said Udi Lebel, a senior lecturer at the Ariel University Center of Samaria who specializes both in social movements and in the psychology of soldiers’ bereaved families.

“The height of the mistake is that at the pinnacle of the Shalit [campaign], the Finance Ministry decided that the state must provide a budget to reimburse families for pressuring the government,” Lebel explained. “It’s absurd. It’s a form of privatizing the activities meant to obtain their freedom.”

The IDF officially classifies Baumel, Feldman and Katz as “missing.” The soldiers’ parents have fought periodic IDF initiatives to declare the men dead without producing proof of their fate.

Thirty years after last reveling in her son’s company at a Lag b’Omer picnic, Baumel’s mother, Miriam, retains hope.

She and her late husband tirelessly knocked on every door to obtain Zachary’s freedom. They met Israeli government leaders, IDF brass, foreign officials, Red Cross representatives, Diaspora Jewish community members, journalists — whoever might help obtain proof of their son’s fate. They lobbied the U.S. Congress to pass legislation that President Bill Clinton signed into law in 1999, calling on the State Department to press Arab governments to provide information on the three Israeli MIAs.

For many years, the Baumels sent Purim baskets and Rosh Hashanah cards to the Feldmans and Katzes. They met occasionally with Arad’s family. Now the MIA families maintain only sporadic contact. Life goes on, Miriam Baumel explained. Children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren occupy everyone’s time, including her own.

The only relatives of an MIA or former MIA with whom she speaks regularly are the parents of Yossi Fink, who was abducted in Lebanon in 1986 and returned, dead, 10 years later.

This week, Baumel spoke about her son at events in their Jerusalem synagogue and in Yeshivat Har Etzion, the institute where he combined Torah study and military training.

Later this month she will travel to England to seek out a British diplomat who reportedly witnessed the parading of three kidnapped Israeli soldiers — perhaps her son, Katz and Feldman — through Damascus streets just hours after their capture. She will address Jewish audiences in London and Manchester to rally support.

On the visit, Baumel will wear a button sporting her son’s image. She may also wear the chain holding the slice of Zachary’s dog tag that PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat handed to an Israeli official in 1993.

“Optimism is not a word to use here,” she said. “What shall I call it: obdurate, unrelenting? I refuse to give up because we [must come] to some resolution here. I have to do what needs to be done until I get my answers.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.