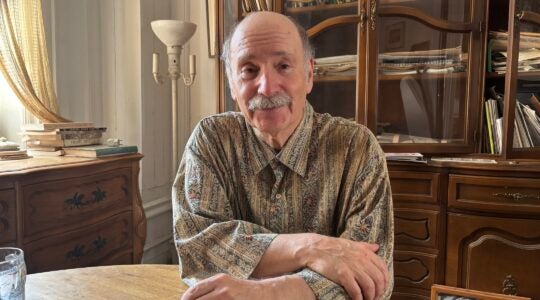

Genghis, caretaker of the mikvah at the Derbent Jewish Community Center in the Russian republic of Dagestan, striking a pose worthy of his name. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

An awkward silence set in between me and Genghis after he tells me that I am welcome to spend the night at the Derbent Jewish Community Center, but that I first need to “get clean” in the mikvah.

I have not heard of congregations with mandatory ritual immersions for visitors, but this is my first visit to a center for Mountain Jews and I am open to believing almost anything about this tough and ancient community of Hebrews, with their elaborate system of superstitions, strong military tradition, unabashed disregard for women and, until recently at least, penchant for bride kidnappings.

But as it turns out, a new anthropological discovery is not in the cards for me. The shower in my room is broken and Genghis (“Like Genghis Khan,” he says, to make sure I spell it correctly) is simply offering that I lather up in the shower adjacent to the actual mikvah.

The Derbent Jewish Community Center in the southern Russian republic of Dagestan was thoroughly renovated in 2010, and now features a kindergarten for some 30 toddlers, a wedding and reception hall, kosher kitchen, small museum and tea corner open to the city’s 500-odd Jews.

On the flashier third floor are two rooms for guests, who pay about $30 per night to stay in this Jewish island in a predominantly Muslim ocean whose traditionally friendly attitude toward Jews has been marred in recent years by a radical fringe which may be growing.

I am in Derbent to find out how the community is coping after the near-fatal shooting last month of its chief rabbi, Ovadia Isakov, who was shot in front of his home at night by several assailants the government suspects were Islamists. It followed an earlier attack on the synagogue last year, when a small bomb went off in its interior yard.

The presence of Isakov, a 40-year-old man who is slowly recovering in Israel, is felt everywhere in this place, from the fancy wooden synagogue where convening a minyan is a daily struggle, to the kindergarten which opened only three years ago and where Isakov used to teach. The kids only know he is in Israel and, based on their experience from his previous long stays there, are all expecting him and his wife to return carrying a newborn baby.

The 25-mile bus ride to Derbent from Sumar, Azerbaijan, proved a good introduction to the two sides of Jewish life here: Coexistence and cultural rejuvenation on the one hand, and escalating hostility on the other.

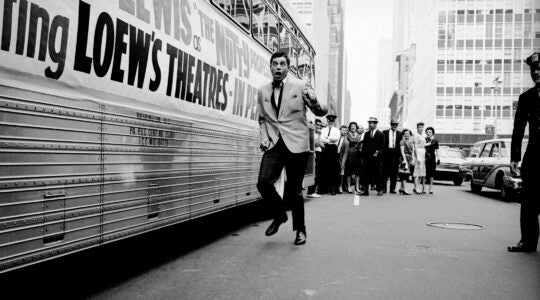

An elderly resident of Derbent, a town in the Russian republic of Dagestan, attending the mikvah at the local JCC. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

I experienced both because I traveled from Azerbaijan to Russia on an Israeli passport, whose holders enjoy automatic visas to both countries. But not without a great deal of head-scratching by potbellied rural border policemen, who blew my cover in this dangerous area with their loud consultations, in which the words “Jew” and “Israeli” were used interchangeably.

It triggered an interesting reaction by people around me as we waited in a hot and stuffy hall to have our passports stamped. The discovery prompted a few young, bearded men to try and engage me in a staring match, spiced with what clearly were anti-Semitic obscenities, and escalated into them running stiff fingers across their throats. Then they offered that I ditch the bus and join their cab. They would take me wherever I needed to go.

It was then that Artur Mirzoyan, a loudmouthed and portly Russian border guard, entered my life with a menacing air swat of his baton in my direction — his way of inviting me to approach. Things appeared to deteriorate as he led me into an interrogation room, ignoring my pleas about needing to stay with the bus.

When we arrived, he turned on the air conditioning and told me to write down two names: Natan Levayev from Netanya and Edik Zacharov from Hadera, two Jews from Derbent who left 20 years ago. I needed to tell them that Artur sends his regards when I return. Then he took my passport. A half hour later he returned it to me. “Time for you to get on the bus,” he said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.