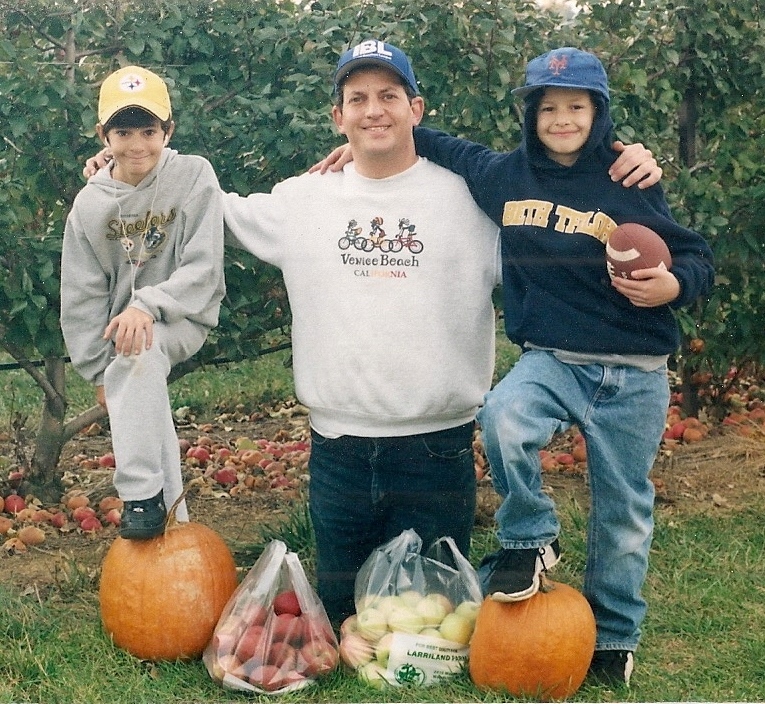

Hillel Kuttler is flanked by sons Yossi, left, and Gil in one of their apple-picking adventures years ago at a Maryland orchard. (Courtesy of Hillel Kuttler)

BALTIMORE (JTA) – Beyond the rusty orange leaves, the sky hugging the orchard flourished in pastel blue – a hue that surprisingly didn’t define my mood while stretched out upon the grass, head nestled in interlocked palms that sweet October day.

Surprisingly because the Sunday afternoon outing marked a jarring wrinkle in a cherished autumnal tradition. With one son serving in the Israeli army and another participating in a post-high-school one-year program in Jerusalem, this apple-picking foray would be my first as an empty nester.

I’d dreaded it – and even with Hanukkah seemingly way off, holiday implications would surely be felt.

Every apple-picking venture, after all, concluded thus: Having driven us the 45 minutes home, I’d promptly lay the three bulging bags of Granny Smiths on the kitchen floor; peel, core and slice most of the apples; and drop the bounty into a pot until the brew of fruit, water, sugar and cinnamon reached a pungent boil. With a serving fork, I’d trap apple solids against the pot’s side until the crushed remnants descended and dissolved into the thickening goo.

Then, even before the beige-yellow yumminess cooled, I’d spoon it into just-washed jars that had previously held tomato sauce or salsa. Before twisting the lids tight, I’d stretch plastic wrap across the jar mouths to preserve the contents.

By Hanukkah, we’d be rewarded. When it comes to latkes, we are an applesauce family.

In the decades since graduating college, I’ve become ever-more proficient in the kitchen, creating an expanding array of soups, main courses, breads and desserts. My family has always eaten well, as have Shabbat and holiday guests.

The apple-picking outings leading to applesauce eatings were different, though. No Kuttler had harvested, slaughtered and picked the wheat, meat and produce that became meals — but our own hands had plucked each green apple. And cooking up 25 pounds of the fruit every October proved surprisingly easy and eminently, edibly popular, as our Ratner’s cookbook with the tattered cover attests.

Up to 10 jars of applesauce resulted from an outing, which doesn’t seem like much, considering the quantity of fruit with which we began. But vacuum-packed, they last surprisingly long.

Each Hanukkah, a few jars would be consumed with homemade latkes. We’d also bring a jar here or there to lunch hosts; anyone can present a bottle of wine or a loaf of challah (and I have), but applesauce is different, special.

The rest of our picking bounty went for fruit munching and pies. Eventually the supply ran out; we’d have to bide our time for the next autumn harvest.

Autumn Sundays are best lived with country drives, small-town lingering and apple picking. But on this drive west, I felt a pit in my stomach. My sons had left home each of the past two Labor Days. Each transition hurt, but defense mechanisms readily kicked in: Yossi’s bed sat unmade because he’d return in a few months to visit; the history books on Gil’s floor still remain where he’d prefer them. I convinced myself I could adjust to their long-term absence because for so many years, they had spent part of each week at their mother’s, anyway.

Going to Larriland Farm this time would be different because the two hours we used to spend at the Howard County orchard were so wonderful. The open fields always beckoned with football-catch opportunities. One son would snag a rotted apple to heave at a tree to see how gross the splattering might be; the other offered an apple distance-throwing challenge. We’d chomp on Granny Smiths while meandering down a line of the low-hanging, vine-like branches, juice dripping down mouths and onto sweatshirts. We’d pose for pictures, one year’s portrait evolving into the next, and we could still match each image with the football game that had been broadcast on the car radio driving home.

Now there was no catch, no splatters, no portraits. The family’s moments in that place and time had passed. More than 15 years – vanished. It’d be painful to return.

This time, there weren’t even Granny Smiths, the boys’ favorite – they wouldn’t be ripe for another week, the woman at the cash register said. So I snagged some reddish Staymans, a tart alternative, and ate my way down the 300-yard-long row. On this first day following Sukkot, the harvest holiday, my plastic bag gradually filled and bulged with apples. This year the one bag sufficed.

I photographed some hanging clusters of Staymans. At row’s end, the comforting sun couldn’t be ignored. There, at the property’s fence, I lay down and stared up, reveling in nature’s glorious setting. The branches above rustled loudly, and an acorn fell nearby. I smiled and, after 10 minutes, arose comforted. The orchard’s row remained devoid of people, as if the agricultural ghost town were all mine. I turned a corner to follow another row out. Two young women held hands, stretched out on the lawn beside their bags of pickings, basking in the warmth I’d just devoured.

“A day doesn’t get more perfect than this,” I said.

“That is so true,” one woman responded, wishing me a pleasant day.

The orchard felt far less lonely and ghostly, less bittersweet – just sweet. A hay ride filled with children rolled on nearby. On the drive home, the Ravens were demolishing the Falcons.

Before Hanukkah comes, the fruit will be made into a fresh batch of applesauce. By then, the remaining two containers of 2013 vintage will be gone.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.