JERUSALEM (JTA) – The shrapnel that exploded into Asaf Ventura took a lot away from him: His right hand and torso were shredded and his thoughts were scattered. He was unable to fire his gun, swing his tennis racquet of maintain focus.

But over time, Ventura came to realize he had also gained something from the injuries he endured during a 2002 mission with his army unit in the West Bank. He had a new perspective, which turned out to serve him well as an industrial designer.

“I remember in the hospital thinking, ‘I’m only 22 and I’ve lost my body and my looks. I can’t do any of the things I used to do,'” he told JTA. “As a designer, though, I learned I have an advantage. My work comes from my feelings, and I know what it is to suffer and to have a disability. I can use technology to create things that other people wouldn’t think of.

Ventura went through years of intensive and painful rehabilitation to regain control of his body and mind. Only then, at the age of 28, was he able to enter the prestigious Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. Now 35, he credits his experience at the school with enabling him to turn his struggle into creativity.

“This is where everything came together, my past and the tools they gave us at the academy,” he said. “They demanded a lot of me, but they supported me and brought me back to real life. I learned from the best teachers and collaborated with really talented people.”

Bezalel, a 111-year old mainstay of the Israeli art world, is known for producing top-notch talent in a variety of fields. The school also prides itself on promoting an inclusive creative process for people with disabilities.

Visitors viewing artwork at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design’s annual student exhibition in Jerusalem, July 2016. (Courtesy of Bezalel)

About a decade ago, Bezalel started a class in industrial design for people with special needs. Over the years, students have created dozens of products: costumes that encourage children to move during physical therapy; air-cushioned prosthetic legs with superhero designs; fashionable clothes that people with limited range of movement can easily get on and off.

Due to this kind of work, Bezalel in December won the $50,000 Ruderman Prize in Inclusion, which recognizes organizations that foster the full inclusion of people with disabilities. The Ruderman Family Foundation has been awarding the prize for the past five years; this year the $250,000 was split among five organizations around the world involved in art, technology and media.

“We loved the fact that Bezalel is a very well known art and design school, and not a disability organization, yet they still choose to include people with disabilities in what they do,” said Shira Ruderman, the Israel director of the Ruderman Family Foundation. “We think they are an example of how Israel can use innovation to change the Israeli mindset on disability.”

With the prize money, Bezalel will launch two undergraduate courses next fall in “inclusive design.” And this week, the school began awarding scholarships — worth more than $1,000 each — to students whose final projects are in inclusive design.

“We are committed to increasing awareness of people with disabilities and the difficulties they face,” said Liv Sperber, the vice president for international affairs at Bezalel, who applied for the Ruderman Prize. “This allows us to get more students involved in creating beautiful and inclusive designs.”

Luca Dalcera, 28, learned Monday that he is eligible for a scholarship for his project. In his fourth and final year of school, he is designing an inflatable pillow to help lift a person with mobility issues out of a seat. The idea came from helping manage the care of his wife’s grandfather, who has Alzheimer’s disease and is relegated to a chair.

“To pick him up takes two people because he’s a big guy, so that means a family member has to be around 24/7 in addition to an aid worker,” Dalcera said. “The situation is very difficult for the whole family. So I wanted to create something that doesn’t solve the problem, but at least eases it.”

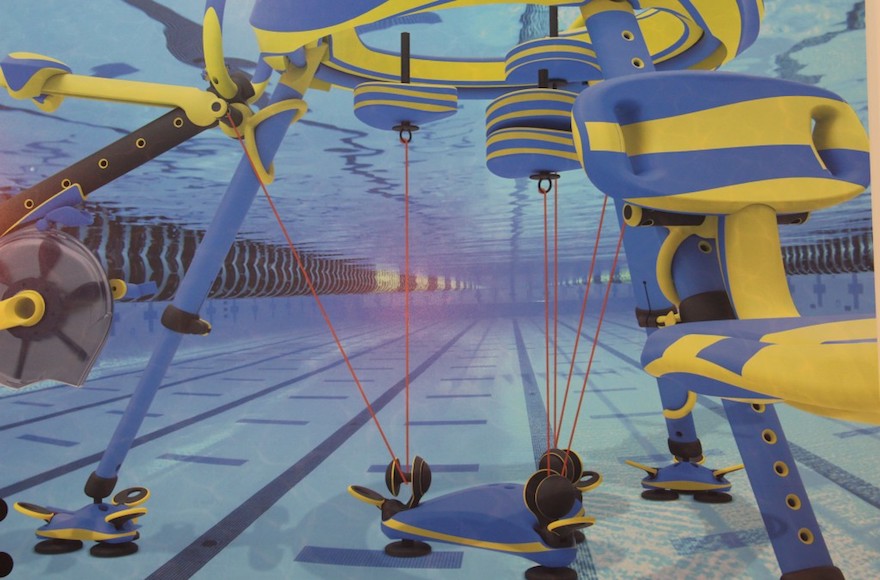

A promotional photograph of Asaf Ventura’s Venduza floating gym (Courtesy of Bezalel)

Like other fourth-year students, he is in the conceptualizing stage of his project. Starting next semester, Dalcera plans to begin developing and testing designs. Money is tight, he said, and the grant will help him “create a better project” than he could afford otherwise. Dalcera is already working on a patent for the design.

There were no grants when Ventura graduated from Bezalel in 2015, but he said there were other forms of support. The school challenged him like any other student, he said, but also accommodated his cognitive and physical disabilities with services like mentors and options for test taking.

For his final project, Ventura built a floating gym for people rehabilitating from injuries. Over the six month-plus process, he was helped by some of the people who were part of his own rehabilitation. Madatech — the national science museum, where he interned for two years before Bezalel — let him use its tools and space. And wounded soldiers at Beit Halochem Haifa, the army center where he did more than four years of intensive rehabilitation, helped him test his designs in the training pool.

“In the pool, people can do all kinds of things they wouldn’t be able to do otherwise,” Ventura said. “They are lighter, of course. But also, they don’t have to feel ashamed of their bodies. Underwater, nobody can see your scars.”

The July before Ventura’s graduation, Bezalel displayed the gym, which he dubbed the Venduza (a portmanteau of his last name and “meduza,” Hebrew for jellyfish), along with hundreds of other students’ art and design projects. Bezalel’s annual exhibition draws some 25,000 people over the course of a week. Ventura appeared on Israeli TV and had visits with several government ministers.

He went on to found a company called Left Hand Design, aiming to bring the Venduza to market. Ventura now lives with his father in Haifa and has taken out loans to produce an upgraded prototype of the gym. He is looking for investors. In the meantime, Ventura also works part-time at Madatech, where he designs exhibitions.

Avital Sandler-Leoff, the director of JDC-Israel Unlimited — a partnership between the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Ruderman Family Foundation and the Israeli government — said not all people with disabilities are able to find the support Ventura did. The country is 30 years behind the United States when it comes to services for people with disabilities, she said, and the lag is reflected in social attitudes. According to a JDC study, more than half of Israelis are not willing to be neighbors with or rent an apartment to someone with a mental disability.

But Israel’s embrace of high tech has driven progress on inclusion lately, and institutes of higher education have the potential to take the lead, Sandler-Leoff said. Her group plans to launch a program for autistic students at three universities this month and a curriculum on disability studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem next month.

“There are more and more places like Bezalel, where a new generation of young people are saying, ‘We want to be part of society. Let us contribute,'” she said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.