(JTA) — The text messages started pouring in at 6:30 a.m., as Tracey Rubenstein was getting her kids ready for school. By the end of the day the Boca Raton, Florida-based social worker had spoken to most of her clients, either in person or via text. They were shocked, disappointed, sad and scared.

The reason: It was the morning after Election Day, and Donald Trump had just been elected the 45th president of the United States.

Over the next few months, about 80 percent of her clients would cite the election and its aftermath as a new source of fear, sadness or anxiety in their lives.

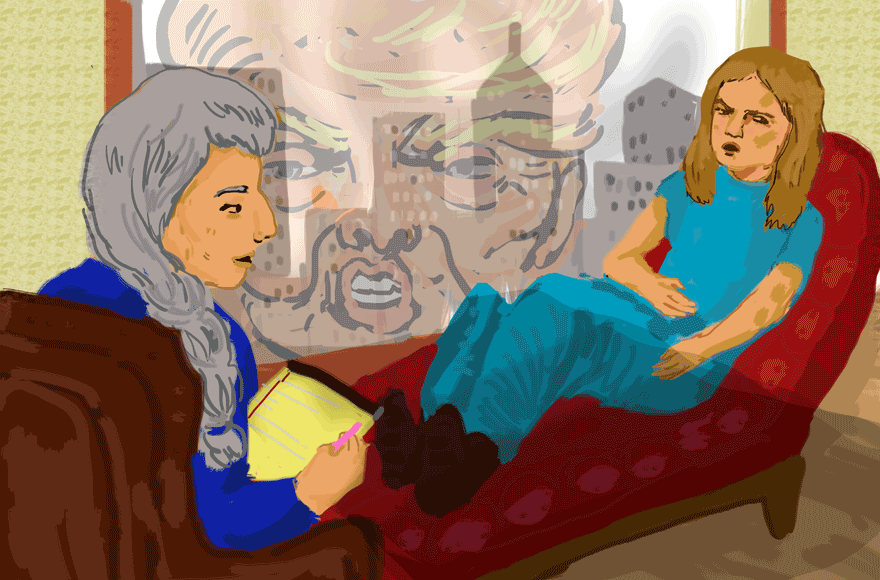

“This is anxiety on a national level, on a level of existential crisis for some people, of national identity,” Rubenstein told JTA.

Tracey Rubenstein, a Florida social worker, said about 80 percent of her clients have cited Donald Trump as a new source of fear, sadness or anxiety following the election. (Courtesy of Rubenstein)

Jewish mental health professionals like Rubenstein say they have seen an unprecedented increase in stress, sadness and other negative feelings that clients are directly tying to the election and its aftermath.

Their testimonies speak to a larger trend: A January study by the American Psychological Association found that more than half of all Americans cited the political climate as a very or somewhat significant source of stress.

Elections usually lead to discontent from the losing side, but not anxiety and depression, said Sam Menahem, a psychologist based in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

“Every election people might talk about it a little bit, they don’t like the candidate that won, but it doesn’t make them more anxious or depressed,” said Menahem, who has been practicing psychology for 44 years. “They didn’t get their way, whether it’s a Republican or a Democrat, but I’ve never seen anything like this — never.”

He estimated that 60 percent of his patients were “experiencing exacerbation or worsening of symptoms after the election.”

Indeed, the APA survey found that the average stress level saw its first “statistically significant increase” since it was first conducted a decade ago: from 4.8 to 5.1 on a 1-10 scale in the period of August 2016-January 2017.

Much of the anxiety can be traced to the surprise victory of an unusually polarizing candidate over the apparent front-runner and more conventional politician, Hillary Clinton. Jewish voters supported Clinton over Trump by a margin of 3-1. Consequently, they are over-represented among people disappointed by Trump’s victory.

As to the degree of that disappointment, mental health professionals and patients point to all the things that make Trump unconventional: his impulsive tweets, his thin skin, his embrace of various conspiracy theories, his lack of political experience and the apparent chaos surrounding his inner circle in his first months in office, to name a few.

Gary Shteyngart said the election changed the nature of his therapy sessions. (Brigitte Lacombe)

Gary Shteyngart, a satirical writer who has authored several acclaimed novels including “Absurdistan” and “The Russian Debutante’s Handbook,” said the election changed the entire nature of his therapy sessions.

Even many people not suffering from a specific mental health condition are experiencing negative moods, said Donna Moss, a social worker in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

“We’re getting more people who don’t have depression and anxiety just feeling bad as a new normal,” Moss told JTA.

Peninah Feldman, a 26-year-old doctoral student in plant biology at Rutgers University, said she has talked about the election “a lot” in her weekly therapy sessions. She sees a clear demarcation in her mental health prior to and after the election.

“I can so clearly in my mind break it down, what’s my mental state before November and what’s my mental state after, and it’s so different,” Feldman told JTA. “I spend so much of my time stressing in a way that now I just consider normal.”

She described Trump’s election as “an event that really shattered my faith in the essential goodness of the world.”

One 25-year-old Jewish college student in therapy told JTA that Trump’s election caused him to question his country in a way he had never done before.

“It’s the first time that I’ve really questioned the values of Americans as a group. I felt that there have been other traumatic and tragic events in my lifetime in America, and they’ve been ones that have galvanized and unified us as a country, like 9/11 and the economic crisis,” said the student, who asked that his name not be used. “I’ve never felt that the core fundamental values which I believe our country is built on were in jeopardy the way I did after this election.”

Moss’ clients have described similar feelings.

Donna Moss, a social worker in New York, said that for many patients, feeling sad has become “a new normal.” (Courtesy of Moss)

People think “no matter what I do I’m not going to be able to have the life I expected, or give my children the life I expected to, when the whole foundation of our institutions is crumbling,” Moss said. “There’s a real sense of dread and frustration, and depression, too.”

Political polarization has spilled into people’s personal lives, threatening to tear apart close relationships, said Nancy Kislin, a social worker in Chatham, New Jersey.

Kislin said that she had clients who had ended romantic relationships based on disagreements over Trump.

“I’ve never seen this before,” said Kislin, noting that she had worked in private practice for 13 years, during the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Seth Grobman, a clinical psychologist in Davie, Florida, said patients have ended relationships with family members and friends due to post-election political disagreements. To be sure, political polarization isn’t the only factor in play, he said, noting that widespread social media use was also to blame.

“Social media lowers the inhibition of people to express themselves, like the old adage that you don’t talk about politics and religion over dinner, but that is a policy that does not exist in the cyber world, so topics that ordinarily are considered to be potentially taboo or disruptive to a relationship become — that concept erodes,” Grobman told JTA.

Moss said mental health professionals aren’t immune to post-election anxiety and stress.

“I myself have been extremely angry and frustrated and paralyzed as well, and when they say this to me I really am stuck with how to respond because I’m stuck with the same feelings, so it feels very paralyzing both from their side and from my side,” she said.

The stress has caused Moss to think about alternate career paths on more than one occasion.

“I think about taking a break all the time, I wish I could. It’s pretty overwhelming. Mostly I just make jokes about it,” she said.

Trump supporters have taken note of the anxiety among his opponents.

“I was not happy with the results in 2008 and 2012, and I’m sure some of you weren’t that happy, either,” Fox News host Sean Hannity told viewers soon after the election. “Did you see me throwing a temper tantrum? Was I crying hysterically? Was I carrying on because I didn’t get my way or you didn’t get your way? Of course not, because that’s not how adults act.”

Amid a new reality, people are still finding ways of coping.

Feldman, a modern Orthodox Jew, said increased anxiety has brought her closer to her faith.

“I definitely feel like it’s pushed me to have more faith in God — which has never been my thing — but I feel like it’s become like a lifeline at this point, if I don’t have that I feel very overwhelmed,” she said.

Others are turning to meditation and exercise practices to deal with anxiety. Annie Moyer, a yoga instructor in Arlington, Virginia, said that the week after the election, people came into the studio where she works “just weeping their way through class.” Months later, the yoga studio still serves as a place for solace.

“Even though people aren’t crying anymore about it, all those needs are still in place,” Moyer said, adding that there are “people coming to relieve stress and anxiety, people looking for community and connection with each other. That’s always been what our studio is about, but it seems especially poignant right now.”

Community and civic engagement also serve as a coping mechanism. Rubenstein encourages people to become involved in causes important to them “as a way of coping with their fear, or their anger, or their anxiety.”

Sam Menahem, a New Jersey psychologist, said many of his patients have experienced a worsening of their symptoms since November. (Courtesy of Menahem)

“[N]ow my approach has been much more about empowering people to do what they can do, to contribute in their way, whether that means contributing financially to causes that they support, or calling their representatives in Congress or in their state legislature, or writing letters or signing petitions, or volunteering their time or going to town hall meetings,” she said.

The 25-year-old Jewish college student who asked to remain anonymous said that hearing about Trump resistance protests and attending a Women’s March event helped ease some of the anxiety he felt after the election.

“I feel stronger than I did initially after the election because I feel that there’s a unified resistance movement against the xenophobic ideals represented in my opinion by our president,” he said.

As the reality of a Trump presidency settles in, Menahem predicted that people will acclimate to a new reality.

“I think they’ll get used to it — unless he does something really, really wild like start a war,” he said.

Rubenstein said a complete return to the pre-election reality may not be ideal.

“I don’t know that the goal should be to get used to it,” she said. “I think there’s something very extraordinary going on with this president and I don’t want to normalize erratic behavior, or behavior that’s not grounded in reality, or policies that are openly discriminatory or harmful.

“I hope that we don’t get used to that, but in terms of finding ways to cope and survive and eventually thrive — yes, I do believe that that is possible.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.