(JTA) — On a chilly fall night in 1993, I learned that the bespectacled army reservist sitting across from me in an Ottoman-era building in Nablus and dining on watery yogurt and hard-boiled eggs was an executive at Israel’s then-nascent Channel 2.

He wanted to continue our chat on Jane Austen — he noticed I was reading “Sense and Sensibility” — but I insisted that he dish about the new TV channel set to launch just a few weeks later.

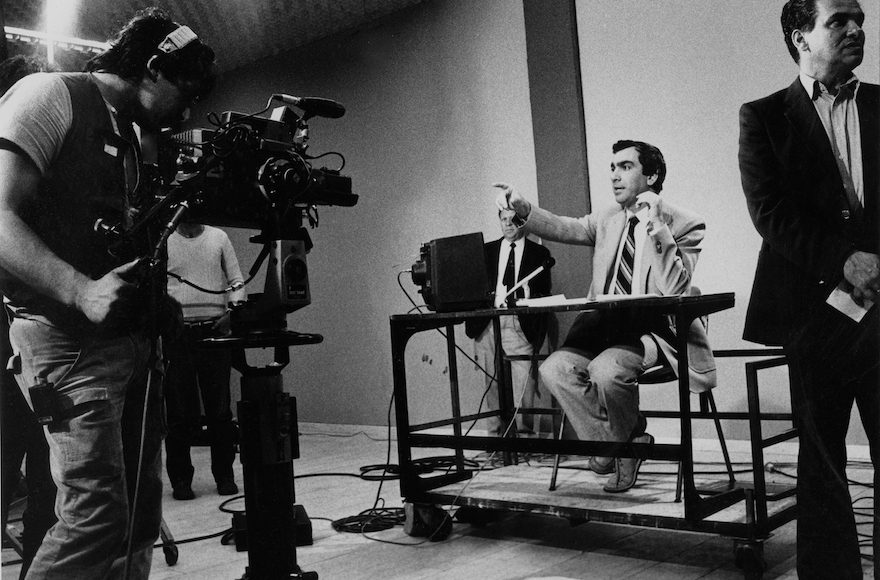

It would have ads! It would have original dramatic programming! There would be three different programming companies!

Gone would be the days when you could stroll in any Israeli suburb past 9 p.m. and hear every television turned to state-run Channel 1 and “

Mabat, like Channel 1, survived the new competitor, as it would an invasion of cable channels and media streams over the following decades. But on Tuesday, after 49 years on the air and with little warning or ceremony, it aired its final broadcast, part of a government plan that will also close down its sister stations on the radio. Israel Radio, launched in 1936, is winding down its programming and will broadcast music and news bulletins until Monday.

The Israel Broadcasting Authority, or IBA, will be replaced by Kan, a new system that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wants in its place. Or doesn’t — it’s hard to keep track.

“The way the IBA was shut down is neither fair or honorable,” Netanyahu said in a statement Wednesday, using the passive voice in a statement about a process he had initiated. A consensus that the public broadcasting authority needed to be reformed broke down among parties angling for political influence and cost savings.

For many Israelis, Channel 1 was like army reserves duty: It was a necessary evil you were supposed to tolerate, something OK to hate. But secretly, you occasionally longed for it, the way you longed for the surprising joys of watery yogurt and hard-boiled eggs. Channel 1 offered camaraderie and, above all, purpose.

Channel 1, like the 40 days a year you spent in fatigues, surrounded you with less beautiful but reassuringly familiar faces who shared a mission: making Israel a better and more secure place.

It was virtuous to a fault. Israelis bought color TVs when they became available in the late 1970s, but only so they could fully enjoy Jordan TV. Israel TV lacked the technology to broadcast color, or so we were told.

Except it did have the technology. One Friday night circa 1979 or 1980 at the launch of the weekly movie — a 1950s Western — a technician forgot to turn on the switch that washed out the color.

It was corrected to a black-and-white wash within minutes, but the secret was out and it was infuriating: We had been under the impression that Israel’s government-run broadcaster couldn’t afford color TV. But not only could the government afford it, it was actually paying extra money for technology that could keep everything black and white.

If the reasoning IBA eventually proffered was perverse, it was perverse in a way that made sense in a country just emerging from socialism: We are austere. We are serious. We can’t afford to pretend that we can afford it.

Color soon came to TV and, under the liberal economic policies of the Begin government, markets opened up in Israel. There were more cars available. Travel abroad was easier, and travelers returned home hankering for — and eventually finding — more varieties of cuisine, more diverse fashion.

Channel 1 persisted, along with its quirks.

Animated cartoons were available just once a week, early Saturday evening, when the broadcast was given over to Arabic-language television. (You knew it was Arabic TV because the subtitles switched places: Arabic was on top, Hebrew along the bottom.) Why were Popeye and Little Lulu kosher for the children of Umm el Fahm and not of Tel Aviv? (Of course, children everywhere watched.) Who knows, but I’d guess, again, the ban was a holdover from Israel’s austere beginnings. Arabic-speaking children were not considered part of the socialist experiment and could luxuriate in the decadent joys of aimless, violent humor. Israeli kids deserved stricter fare embodied in the earnest, hectoring young women who helmed Hebrew-language children’s TV.

Friday nights were movie nights, consistently heavy, depressing fare — lugubrious numbers like “Lust for Life,” but also classic Westerns like “Shane.” Comedies were scarce — I can’t recall any — because you were supposed to Learn a Lesson. The movies were followed by a palate-cleansing if inoffensive sitcom: for years, “Night Court.” (For racier fare, you’d have to switch over to Jordan TV for the inane innuendo on “Three’s Company.” The kingdom descended from the Prophet was more profane than the secular Jewish paradise.) There was a news recap, a reading from the weekly Torah portion and then the national anthem.

Friday afternoons were the country’s guilty secret: the “Arab movie,” ostensibly, again, a nod to the country’s Arabic-speaking public, but really a break for all comers from the channel’s deadly serious fare. The whole country seemed to tune in but, tellingly, each Jewish viewer was certain she was the only one to indulge. These movies were everything Israel did not imagine itself to be. They took place in cities teeming with the very poor and the fabulously rich, they delved into wild romantic transgressions, they were high on physical comedy.

Channel 1’s talk shows treated poets like Yehuda Amichai and Natan Zach as celebrities and berated celebrities like Goldie Hawn for not coming to Israel more frequently.

And the music shows — you had to attend an actual rock concert to find out that Israeli musicians could actually rock, hop around the stage and involve the audience in a good time. On Channel 1, these same musicians stood in place and barely moved, as if evidence that Israelis could lift their feet off the floor would subvert Labor Zionist notions of Jewish oneness with the earth.

And then there was Mabat. We mocked its anchors as remote and pompous, but goodness, they were Walter Cronkite-level reliable. They did not hold back in interviews and irked politicians of all stripes. They stuck to just the facts, ma’am. When Haim Yavin, who anchored the nightly newscast from 1968 to 2008, pronounced in 1977 and then in 1992 that the elections had produced a “mahapach,” an upheaval — well, by golly, it wasn’t just a change in government, it was indeed an upheaval. Yavin was consistency defined, opening with “Good evening and greetings to all of you” and closing with “Good evening and much peace from Jerusalem.”

Mabat’s independence may have helped kill it. Netanyahu has never made precisely clear why he wanted the Israel Broadcasting Authority replaced, but for a politician who chafes at any critical coverage, critical coverage from a government-run broadcaster must have been especially galling. (And now he reportedly fears that Kan will also cover him critically.) Haaretz published a rundown of the competing political interests that doomed the IBA, including haredi Orthodox, Russian and pro-settlement parties angling for a piece of the broadcast spectrum and jockeying over who will lead the news and general programming divisions of the new channel.

Channel 1 was likely doomed in any case, as ratings had been tanking for years. It ignored the very idea of competition. Channel 2 broadcast its news at 8 p.m. — Israelis like to go out and meet friends after the news, and Mabat insisted on a 9 p.m. broadcast. By the time Mabat got the memo about competing for viewers and switched its broadcasts to 8, it was too late.

Mabat’s news staff delivered a tearful farewell on Tuesday night. The radio stations are running nostalgic music and news bulletins until they, too, suspend broadcast on Monday at 6 a.m.

It’s no understatement to say that a broadcaster that went virtually unchallenged for decades — until the rise in the 1970s of Army Radio and then the launch of commercial broadcasts in the 1990s — shaped the country in profound ways. The modern Hebrew accent itself was forged by two pioneer radio newscasters: Moshe Hovav, of Yemenite origin, and Drora Hovav, his wife, who happened to be the granddaughter of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the Vilna-born scholar who almost singlehandedly revived Hebrew as a spoken language. Their Hebrew, combining the Sephardic east and the northern reaches of Europe, reinforced that Israeli Jews were One People.

“This has been like demolishing a house,” Yavin, now 83, told i24 news on Wednesday. “You can get me out of Mabat, but you can’t get Mabat out of me.”

You can’t, it’s true, at least for those of us who were raised on Mabbat and Channel 1. The IBA sticks to us like dybbuks of our better selves.

Channel 2, and eventually the flurry of cable channels that came in its wake, reflected Israel as it evolved: loud, raucous, international and at perpetual odds with itself. Channel 1 was Israel as it once aspired to be: tough, serious, analytical and infused with the spare sensibilities of modern Hebrew poetry.

May its memory be blessed.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.