WASHINGTON (JTA) — Among the Jewish men and women with a front-row seat to America’s executive branch, there are Jews who would be president, Jews who are indispensable to presidents and, less happily, Jews who help mire presidents in scandal.

Jared Kushner, President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, is a definite category 2, with rumored ambitions of one day becoming a category 1. Facing allegations that he turned to the Russians for a secure communications channel before Trump even took office, he may be transitioning into the dread category 3. He may yet pull away from the prying eyes of the law, or the move some have called “naive or crazy” may turn out to be far less than it seems.

But if things for Kushner continue to go south faster than a retired dentist from Chicago, here are five precedents, so he knows what to expect.

Judah Benjamin

Judah Benjamin circa 1856. (Wikimedia Commons)

What did he do?

Judah Benjamin was a Confederate who before quitting the Senate — he was a Democrat from Louisiana — defended slavery not once but multiple times in floor speeches. Confederate President Jefferson Davis named Benjamin attorney general and then secretary of war — he was a disaster in that capacity, blamed for munitions shortages and battlefield defeats. That set off unfounded, and anti-Semitic, allegations that he was squirreling away funds for his personal use. Davis, who considered Benjamin one of his closest advisers, pulled him out of that fire and he finished the brief Confederacy as secretary of state.

Oy. How low did he go?

He was a Confederate! He defended slavery! Does it get lower?

The comeback kid factor

Not so great. Benjamin was the only major Confederate figure to choose exile rather than face any music. (Not that there was much music to face for those who stayed; most were rehabilitated.) He became a barrister in his native England.

The shanda factor

When you are asked “Who was the first Jew in an American Cabinet, you reply “Oscar Straus” and then mutter, “Unless you count Judah Benjamin, which nobody does.”

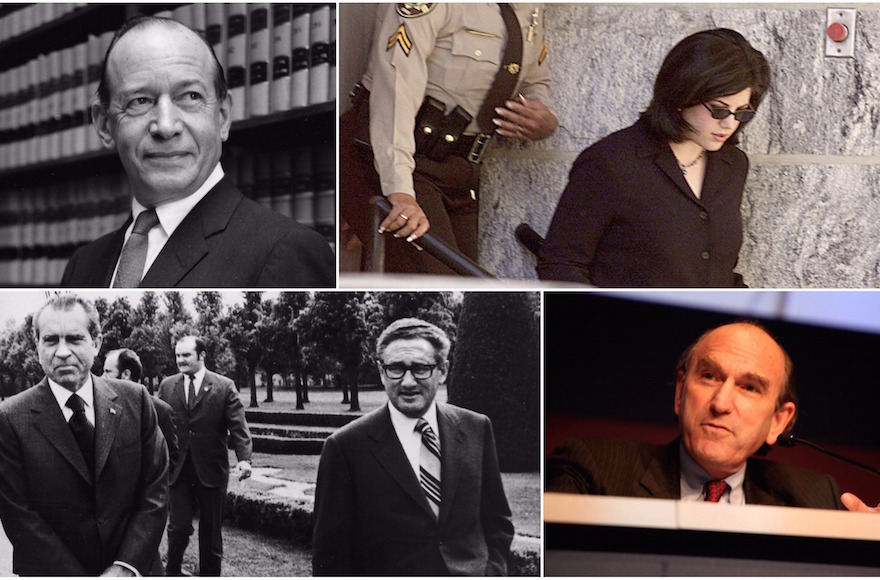

Abe Fortas

Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas in 1965. (PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

What did he do?

He was an associate Supreme Court justice who resigned in 1969 when it was revealed that he was on the payroll of the family foundation of a family friend, Louis Wolfson, who was indicted for stock manipulation.

Oy. How low did he go?

Not so low. He was not the first Supreme Court justice to resign in disgrace — that would be John Rutledge, the second justice named to the court, who quit after delivering a bizarre harangue against a treaty with Britain. Then there’s John Archibald Campbell, who quit to join the Confederacy.

And Fortas’ scandal did not bring down a presidency; it did, however, tarnish a presidential legacy. A year earlier, in 1968, Lyndon Johnson, who named Fortas to the court in 1965, had hoped to name Fortas as chief justice. Senate Republicans and “Dixiecrats” — conservative Southern Democrats — fiercely resisted because of his liberal views. (Some Northern Democrats in the Senate said they smelled the whiff of anti-Semitism, but that was never proven.)

Johnson’s presidency fell under the axe of the Vietnam War, and learning just months after he relinquished the White House that a favorite protegee was in disgrace didn’t burnish LBJ’s reputation.

The comeback kid factor

No real comeback. Fortas returned to private practice and maintained his innocence until he died in 1982.

The shanda factor

There was a perception that since Louis Brandeis ascended to the Supreme Court in 1916, there was a “Jewish seat” on the court. Fortas replaced Arthur Goldberg, who replaced Felix Frankfurter, who replaced Benjamin Cardozo. That ended with Fortas; the Supreme Court would not have a Jewish justice until Ruth Bader Ginsburg was named in 1993.

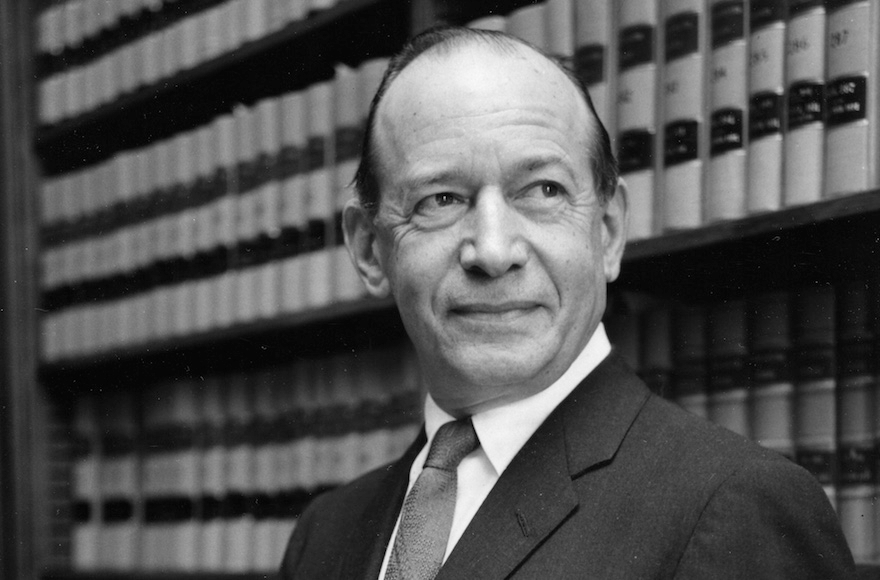

Henry Kissinger

President Richard Nixon, left, with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger during Vietnam War peace talks in Paris in 1972. (Keystone/Getty Images)

What did he do?

What he didn’t do: Authorize a break-in at the opposition party’s headquarters. Kissinger was one of the few figures close to Richard Nixon whose career survived his resignation over the Watergate scandal in 1974, remaining as secretary of state under Gerald Ford.

What he did do: As Nixon’s first-term national security adviser, Kissinger authored the carpet-bombing strategy that was aimed at leveraging an “honorable” end to the Vietnam War and instead prolonged it — and spread the chaos and carnage to neighboring countries, notably Cambodia. Kissinger signed off on each and every air raid.

Kissinger insists to this day that civilian casualties were minimal. In 2014, he said the Obama administration’s drones were killing more civilians. In 2003, he cited government figures in writing that the U.S. bombing raids on Cambodia — conducted in secret, without congressional authorization — killed 50,000 civilians. Other estimates range from 150,000 to 500,000 civilians.

Watergate remains the template for presidential scandal, but the perception that Nixon and Kissinger perpetuated a meaningless war costly in civilian casualties is the darker taint on their legacy. A cottage industry of activists who would like to see Kissinger, now 94, tried for war crimes persists to this day.

Oy. How low did he go?

Kissinger, whatever his protestations after the fact, seemed in real time callous about the damage he was causing.

“Well, Mr. President, they claimed to have counted 10,000 bodies up to now and if you cut it in half, there must be another 5,000 that they have killed that we don’t find,” he said in April 1972, describing B-52 sorties in North Vietnam to a delighted Nixon.

Kissinger was equally as sanguine about other American interventions, notably in Latin America, where the Nixon administration underwrote authoritarian regimes. The administration helped manage the coup that in 1973 ousted Salvadore Allende, the leftist president of Chile. Two years later, meeting with Adm. Patricio Carvajal, the foreign minister under Augusto Pinochet, the dictator who replaced Allende, Kissinger derided the staff of his own State Department.

“I read the briefing paper for this meeting and it was nothing but Human Rights,” he told Carvajal, according to contemporary notes obtained by the National Security Archive. “The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there are not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State.”

The comeback kid factor

Kissinger wins the comeback kid stakes. Aside from the occasional pesky protester, he remains an eminence grise among foreign policy advisers. This past election alone, one of the rare agreements shared by Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump was that they should consult with Kissinger.

The shanda factor

None, apparently. The World Jewish Congress conferred a prize on Kissinger in 2014 named for Theodor Herzl, the Zionist visionary.

Elliott Abrams

Elliott Abrams in 2012. (Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons)

What did he do?

Abrams was a cog in the Iran-Contra scandals that engulfed Ronald Reagan’s final two years in office. He was involved in the purchase of weapons for the Contras fighting the leftist Nicaraguan government. Congress banned military aid to the Contras. (The Iran component, which did not directly involve Abrams, was the use of funds from weapons secretly sold to Iran as a means of funding the Contras.)

Oy. How low did he go?

Abrams concealed from Congress, in sworn testimony, the Reagan administration’s ties to the pro-Contra network. He pleaded guilty in 1991 to “two misdemeanor charges of withholding information from Congress about secret government efforts to support the Nicaraguan contra rebels during a ban on such aid,” according to Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh’s summary of prosecutions. He was sentenced to two years probation and 100 hours of community service. President George H. W. Bush pardoned Abrams on Christmas Eve 1992 as one of his last acts in office.

The comeback kid factor

Abrams was pardoned, but in 1997 was suspended for a year by the District of Columbia Court of Appeals bar — so he did not escape entirely unscathed. In June 2001, he was named to a top post on George W. Bush’s National Security Council, and was promoted to a deputy national security adviser in Bush’s second term. Earlier this year, Abrams reportedly was considered, then nixed, for the No. 2 job at the State Department.

The shanda factor

Abrams, a fellow on the Council of Foreign Relations, is a regular on the Jewish think tanker talk circuit. So, none.

Monica Lewinsky

Monica Lewinsky arriving at the Howard County Circuit Court in Ellicott City, Md., Dec. 15, 1999. (Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

What did she do?

Oh, c’mon: She had an affair with President Bill Clinton. He was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for lying about it, but acquitted by the U.S. Senate. The scandal clouded the final two years of his presidency and its aftereffect helped cripple the bid by Clinton’s vice president, Al Gore, to be elected president.

Oy. How low did she go?

Um. We’ll pass.

No, seriously, Lewinsky in retrospect has emerged more as a victim than a perp in this case: of Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s Javert-like eagerness to find something, anything, he could use to indict Clinton and of the slut shaming by Clinton’s allies and the media.

The comeback kid factor

Lewinsky went underground for a decade or so, but since 2014 has emerged as an eloquent spokeswoman against bullying. Last week, marking the death of Fox News Channel founder Roger Ailes, she wrote an “obituary” for the culture of bullying and “gutter” journalism embodied by the conservative network in covering the scandal.

The shanda factor

Lewinsky is not exactly a featured speaker on the synagogue and federation circuit — but then, she never made an issue of her Jewishness, so no surprise there.

At the time of the scandal, more than a few Israeli commentators likened her to Queen Esther, a concubine entwined with a “king,” Clinton, that some Israelis wanted to see taken down for his role in the Oslo accords.

Likened to a queen? A victim after all? We’ll score Lewinsky zero on the shanda scale.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.