SAN FRANCISCO (J. the Jewish News of Northern California via JTA) — “Az men est khazer, zol es shoyn rinen ibern moyl” goes an old Yiddish saying: “If you’re going to eat pork, eat it until your mouth drips.”

Sunday night at Brick & Mortar Music Hall here, the mouths of rabbis and foodies dripped with Peanut Butter Pie with Bacon, a Rabbit Crepinette and a Pulled Pork Potato Kugel with barbecue sauce.

The occasion was the “Trefa Banquet 2.0,” a delicious spread of treif (nonkosher food) made by local Jewish chefs and served up with a side of Jewish learning and — get this! — a communal bracha (blessing) for treif led by a local rabbi.

During what was practically a seder of liturgy, symbolic foods and a narrative recounting of an important Jewish legend, a foundational myth of American Judaism was memorialized, deconstructed — and then eaten.

The original Trefa Banquet was an 1883 event at which leaders of the early American Reform movement made a bold, antagonistic statement by serving nonkosher dishes to commemorate the ordination of the first graduating class of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. As the story is often told, a group of rabbis stormed out in protest and ran off to start the Conservative movement.

Jewish studies professor Rachel Gross talking about the original Trefa Banquet at “Trefa Banquet 2.0,” at Brick & Mortar in San Francisco, Jan. 7, 2018. (Lydia Daniller)

But as Jewish studies professor Rachel Gross of San Francisco State University told the crowd Sunday night, that story is only kind of true.

The San Francisco event was organized by Alix Wall, a contributing editor to J. who writes its “Organic Epicure” column, as part of the Illuminoshi, a not-so-secret organization she founded for local Jews working in the food industry. Following Gross’ talk, an array of Bay Area chefs presented a buffet meal of treif, treif and more treif.

When I first arrived, I struck up a conversation with Rabbi Camille Angel, formerly of Congregation Shaar Zahav, San Francisco’s historically gay synagogue. She proudly identifies as a “second-generation lobster-eating rabbi.”

Her dad was ordained in 1934 at HUC in Cincinnati, the site of the original Trefa Banquet, and she grew up knowing all about that notorious meal, Angel said.

Lobster held a special place in her family. It was, she told me, “our family celebratory meal, but always at home. We only ate lobster out when we were in Maine.” Well, naturally.

They even had a bracha for lobster: “‘Thank you for all gifts of land and sea,’ motzi — then crack it open!”

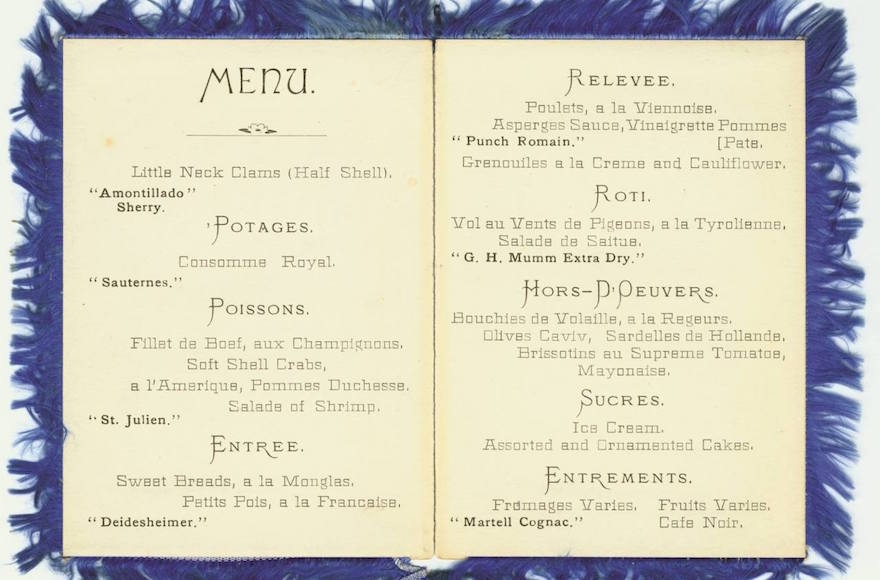

The menu at the original Trefa Banquet. (Courtesy of J. the Jewish News of Northern California)

Angel said her family delighted in this sort of thing.

“My mother loved sending me to school during Passover with a lunch of matzah with ham and cheese,” she said. This led to teasing from another Jewish classmate, who felt this somehow diminished Angel’s Jewish cred.

In the middle of our conversation, Angel called out to a nearby figure, the only person besides myself wearing a kippah.

“Rabbi, what do you have there?” she asked.

Rabbi Sydney Mintz of Reform Congregation Emanu-El in San Francisco looked up.

“Bacon!” she said cheerfully, popping another tiny chocolate cup filled with peanut butter pudding and bacon into her mouth.

Then the learning began.

“Our story starts on July 11, 1883, one of the most infamous days in American Jewish history,” Gross said, setting the scene.

“It was a hot and humid evening in Cincinnati. Two hundred and fifteen guests had assembled at the Highland House, a resort and restaurant, overlooking the Ohio River. They included a who’s who list of the most elite Jewish leaders in the United States, as well as local non-Jewish civic leaders, Christian clergy and professors from the University of Cincinnati.”

The banquet was an elaborate, ostentatious affair: The guests were treated to “an orchestra and elaborate printed menu adorned with bright blue feathers that promised nine courses of French cuisine paired with five alcoholic drinks.” (The French on the menu, she pointed out, is terrible.) “The menu’s list of dishes, its language and its visual appearance all suggest how the celebration was part of the excessive banquet culture of its era.”

A Reuben sandwich at the “Trefa Banquet 2.0.” (Lydia Daniller)

Most of Gross’ material came from the research and work of Rabbi Lance Sussman of Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. Following his lead, Gross argued that to most of the guests, there was nothing remarkable about the food.

“Almost every violation of kashrut was in evidence — seafood, nonkosher meat, mixing milk and meat. This tells us, and we know from an enormous amount of other historical evidence — including cookbooks written and used by Jews — that it was normal for many American Jews in the 19th century not to keep kosher,” she said. “I do not think that this menu was intended to be provocative.”

It is not until Rabbi David Philipson’s eyewitness account of the event written 60 years later in a 1941 autobiography that the myth of the founding of the Conservative movement creeps into the story.

“Terrific excitement ensued when two rabbis rose from their seats and rushed from the room,” he wrote. “Shrimp had been placed before them as the opening course of the elaborate menu.” (In fact, the first course included clams, not shrimp.) Gross said Philipson went on to connect that moment to the founding of the Conservative movement.

Yet the historical evidence points to a different origin of the Conservative movement: the Reform movement’s 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, in which, among other things, they renounced kashrut as an archaic practice, “entirely foreign to our present mental and spiritual state.”

The following year, the Conservative movement’s flagship body, the Jewish Theological Seminary, was founded.

But the legend of the Trefa Banquet makes for a terrific story.

Rabbi Sydney Mintz of Congregation Emanu-El in San Francisco offers a blessing at the “Trefa Banquet 2.0.” (Lydia Daniller)

“The fact that American Jews still tell the story of that night in Cincinnati in 1883 tells us that debates about food practices have been central to the ways that American Jews think about themselves, the stories they tell about themselves and the ways they organize themselves,” Gross said in closing. “American Jews have always had a wide range of eating habits, defining what it means to eat Jewishly in a broad array of practices.”

Before we got to eating, Mintz came up to offer a bracha, substituting “shehakol” for “lechem” in the traditional motzi blessing over bread. In this version, God is praised for bringing forth “everything” from the earth, not just bread — and not just kosher food.

Like Angel’s lobster-loving rabbinic line, many of the Jews at the dinner tied their treif observance to their family’s Jewish heritage.

Wall, for example, told the crowd that her mother was a child during the Holocaust, hidden with a family of Poles; she grew up eating what they ate, including plenty of pork. In this family, an essential 20th-century Jewish story of Holocaust survival is tied to pork. So for Wall, “keeping treif” (if I may coin a phrase) connected her to her Jewish history, just as keeping kosher does for others.

Oded Shakked of Longboard Vineyards told the crowd of growing up in Israel, where his family would go to Jaffa for cheap or even free shrimp.

“The fishermen just tossed them aside!” he said. Again, a family treif tradition.

Israeli vintner Oded Shakked provided the wine for “Trefa Banquet 2.0” and told the crowd of his family’s old trick for getting cheap shrimp. (Lydia Daniller)

“I didn’t grow up with bacon,” chef Ari Feingold told me as he carefully inserted more bits of bacon into the peanut butter dessert.

I met Bryan Tublin of the recently opened San Francisco restaurant Kitava. His restaurant is “fast casual” but gluten free, and focuses on “healthy fats and oils,” “mindful meats” and “conscientious sourcing.” Tublin doesn’t keep kosher, but restaurants like his offer up food with fussy and exacting standards that rival anything in kashrut.

Wall told me the story of a Maryland Jewish family in which everyone loved crab except the man of the house. When the family ate crab, he would outline a mechitza (or more of an eruv?) made of silverware to separate his kosher meal from the crab-spattered table.

As Mintz told me earlier in the evening, “I would rather eat food that’s humanely and ethically raised than kosher.” For some Jews, ethically produced food is their kashrut, and they’re willing to say so publicly. In rejecting kashrut, some progressive Jews keep boundary setting at the heart of their conscientious approach to food.

Judaism — and the history of the Reform movement in particular — is full of this: not a transgression of religion, but transgression as religion. And as a Reform Jew by heritage and an enthusiastic chronicler of our religion in all its unusual forms, I love it.

(This piece was originally published by J. The Jewish News of Northern California as an installment of David A.M. Wilensky’s “Jew in The Pew” column on Jewish ritual and religion around the San Francisco Bay Area.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.