BERLIN (JTA) — Raed Saleh, a Palestinian born in the West Bank, wants to rebuild a synagogue in the German capital. Now the dream of this Berlin politician is a bit closer to reality.

Standing in front of the Fraenkelufer Synagogue on a chilly March morning, the senator and leader of the Social Democratic Party here announced plans for the reconstruction of a building that was largely destroyed in the Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938.

Saleh’s goal, endorsed by Berlin Jewish Community President Gideon Joffe, is to make a statement against growing anti-Semitism in the capital city — and against discrimination targeting Muslims, too.

“If you say you want to support Jewish life in Germany and Berlin and Europe, and you don’t just want to pay lip service, then you have to carry it out concretely,” said Saleh, 40, who immigrated to Germany with his family when he was 5.

He first proposed the project in November in a column in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. His thinking: “He who builds castles can also rebuild synagogues.”

So Saleh campaigned for and won support from the Berlin Senate. The project is still a vision, but no longer a pipe dream.

It’s an idea that would have stunned Joffe 12 years ago, when he was first elected president of the Jewish community.

“I would never have thought that a Berliner of Palestinian background would help the Jewish community,” Joffe said, standing beside Saleh, who was born in a village near Nablus. “I find it to be a fantastic story that allows us to look with hope into the future.”

Also announced Thursday was a plan to renovate a former Jewish orphanage on Auguststrasse, converting it into what would be Germany’s first Jewish trade school. There already is a Jewish high school in Berlin, but the new school would cater to students who are not necessarily moving on to college.

Noting that many Jewish kids have transferred to Jewish schools because of anti-Semitism, Joffe said he hoped the new facility would open in the next two years.

While it will take longer to realize the Fraenkelufer project, Joffe said he would be “very happy to see it become a place for exchange between people, a place where they can get to know Judaism.”

Fraenkelufer, which sits on the banks of one of Berlin’s many canals, is located in a multi-ethnic neighborhood with many Arab residents, a colorful market and shops with Arabic signs.

An interior view of the surviving adjunct building of the former Fraenkelufer Synagogue in Berlin, March 15, 2018. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

For Saleh, that makes it the perfect location for such a project, “especially in a time of increased anti-Semitism, also coming from migrants; especially given that there increasingly are schools where teachers complain that they are overwhelmed with a situation that they can’t control,” he said, referring to anti-Semitism among youth of Arab or Muslim backgrounds.

His idea, still in the early stages, is to build a structure resembling the classical 1916 synagogue by architect Alexander Beer. But rather than erase the recent past, the reconstruction would emphasize the violent rupture of the Holocaust and represent hope for the future.

Saleh said the project is likely to take several years to realize and would cost nearly $30 million. The senator pledged to secure state and federal funding, as well as raise funds from German industry and private donors — including his own young sons. He said they each pledged 20 euro, about $25, from their own savings.

Rebuilding destroyed synagogues is not a new phenomenon in Germany. Since the 1990s, particularly with the influx of some 200,000 Jews from the former Soviet Union, big cities and small towns have taken on projects to build new Jewish houses of worship or rededicate old ones that had been used as storehouses or even barns over the years.

The projects were often intended as proud symbols of a new Germany. But aside from some in larger cities, like Munich and Dresden, few became hubs for growing, active Jewish communities. More often they were used as museums and interfaith meeting centers.

Before World War II, Berlin had some 175,000 Jews and numerous synagogues. The original Fraenkelufer Synagogue could house up to 2,000 worshippers. A few years after it was destroyed in the 1938 pogrom, the architect Beer was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, where he was murdered in 1944.

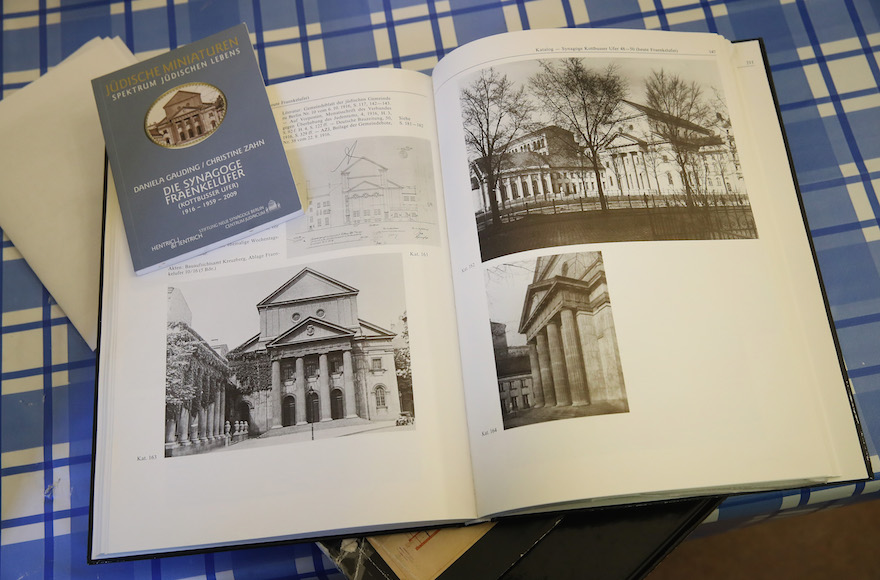

A book shows photographs of the former Fraenkelufer Synagogue, March 15, 2018. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Today, the traditional congregation is small but growing thanks to an energetic group of younger Jews, including native Germans along with those born in Israel, the United States and elsewhere. One of more than a dozen active congregations in Berlin, its members meet in Beer’s small former youth synagogue, which has a balcony for holiday overflow. Men and women sit separately, though without a mechitza, or divider. There are regular Friday night meals and visiting Jewish educators.

The new building would not be used for prayer services but rather for classrooms and other gatherings, including interfaith events.

It is among several projects in Berlin meant to bring together Jews, Muslims and Christians against the backdrop of increased xenophobia and populism. Conservative Rabbi Gesa Ederberg is joining with colleagues to start a multi-faith kindergarten. And the “House of One” – a concept stuck in the planning stage – would be a place of shared worship.

Best estimates there are some 30,000 Jews in Berlin, a city with a population of about 3.5 million. Fewer than 10,000 Jews belong to the official community.

Recent statistics show an increase in anti-Semitic crimes in Berlin, with 288 reported incidents last year compared to 197 in 2016.

An exterior view of the surviving adjunct building of the former Fraenkelufer Synagogue, March 15, 2018. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Though there is no silver bullet for combating anti-Semitism, interfaith meetings are an important plus, said Jonathan Marcus, a gabbai, or sexton, at the Fraenkelufer congregation and one of several volunteers who explain Jewish traditions to visitors.

He recalled a group of visiting Arab teenagers who – surprised by the similarities between the two faiths – asked, “Why are we always fighting with each other?’”

“I said, ‘Probably because we normally look only at our differences, and not at what we have in common.’”

Marcus, who became a bar mitzvah here, also had the chance to welcome Saleh one Friday night and explain Jewish tradition to him.

On Thursday, Saleh told reporters that he had “fallen a little bit in love with this community.”

When fellow Muslims question his commitment to his own community, he tells them that he “would not be a good Muslim if I did not take a stand; a Christian would not be a good Christian if he would stand by while refugee homes burn; and a Jew would not be a good Jew if he stands by when someone tears the headscarf off a woman.”

“I am convinced,” Saleh added, “that one can only combat hate and prejudice with an open door, and this will be a place of open doors.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.