(JTA) — At the beginning of his new book, Matti Friedman writes that “time spent with old spies is never time wasted.” When he went to meet Isaac Shoshan in his suburban Tel Aviv home, Friedman had no idea what to expect — but knew it might be good.

“He was a really old guy who came up to my shoulders,” Friedman tells the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “He told me a story about 1948 that I had never heard before; it took me a few meetings to figure out what he was telling me. From there I was led to other sources, recently declassified files and some oral testimonies that had been recorded by other participants in the Arab Section.”

The result?

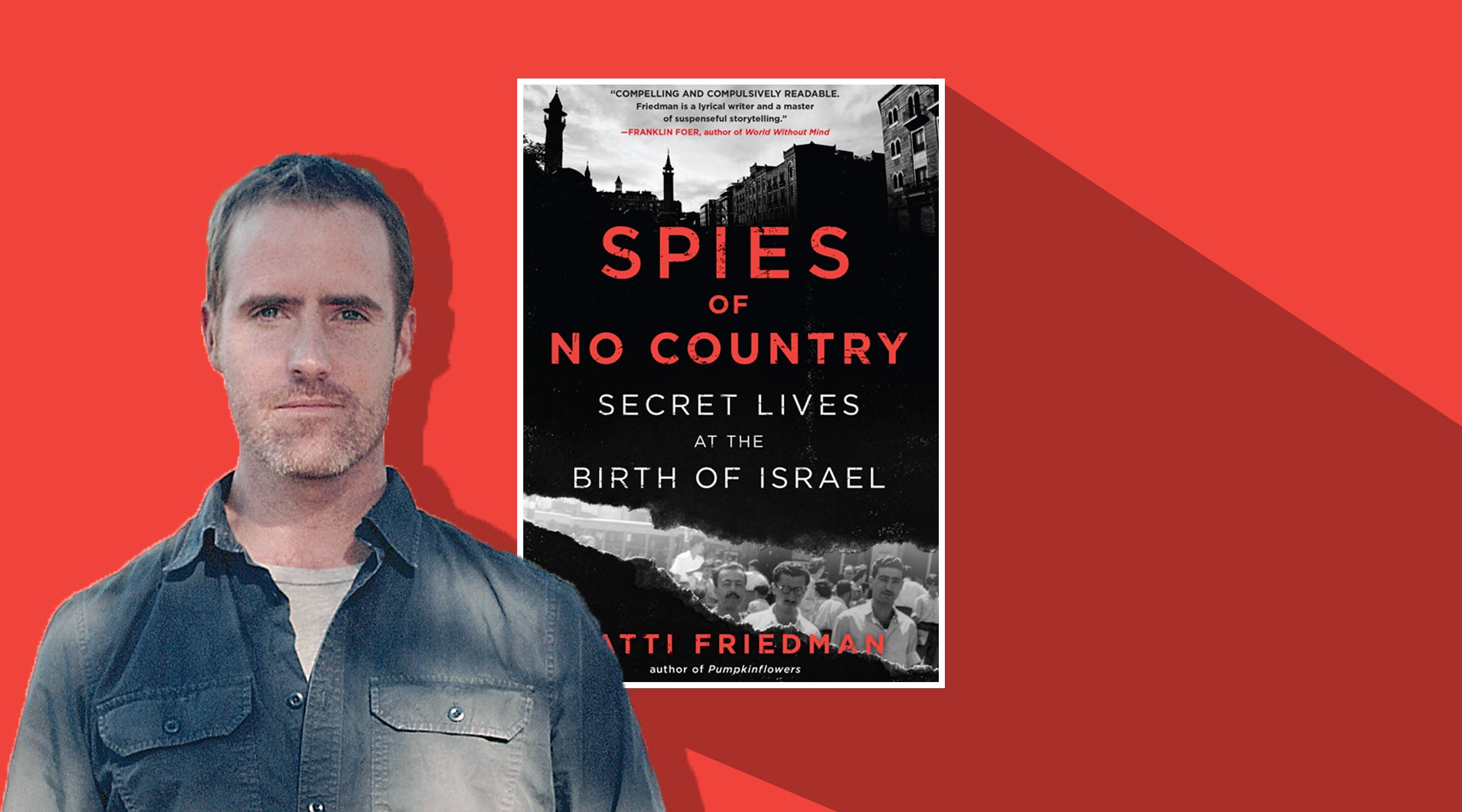

“Spies of No Country: Secret Lives at the Birth of Israel,” which tells the captivating tale of Israel’s first spies, young Jewish men originally from Arab countries who could slip across borders undetected. They were part of the “Arab Section” of the Palmach, Israel’s prestate force that would turn into the Israel Defense Forces.

“Spies of No Country” follows Isaac’s story, alongside those of three other men: Gamliel Cohen, Havakuk Cohen and Yakuba Cohen. They weren’t related — Cohen is a common last name — yet they all shared the experience of being Mizrahi Jews in a country where the majority of Jews had roots in Eastern Europe.

As Friedman explains, “In the Zionist movement in those years — we’re talking about pre-1948 — almost everyone is European or Eastern European. Nine out of every 10 Jews were of European descent. The community of Jews who came from Islamic communities was marginal; they didn’t seem like Jews. These people spoke Arabic — they had a different kind of Judaism. And the Zionist movement didn’t know what to make of them. Sometimes they were considered really interesting and exotic, but [most] times they’re disregarded and pushed aside.”

In the nascent world of Israeli intelligence, in a country in which Mizrahim still complain of discrimination, the book’s heroes saw their identity as Arab Jews respected for the first time.

“The very thing that makes these guys marginal — their Arab identities — becomes their ticket into the holy of holies, the Palmach,” Friedman says.

Friedman, a journalist and New York Times op-ed contributor, was born in Toronto and now lives in Jerusalem. Between 2006 and 2011, he was a reporter and editor for The Associated Press in Jerusalem. His first book, “The Aleppo Codex,” told the tale of an ancient Bible manuscript that ended up in a cave in Aleppo, Syria, and his second, “Pumpkinflowers,” narrates his experience as part of a group of Israeli soldiers responsible for holding a remote outpost in Southern Lebanon in the 1990s.

“Spies of No Country” chronicles the experiences of undercover agents in various Arab communities in the lead-up to Israel’s War of Independence in 1948. After Israel’s founding, it shifts to Beirut, Lebanon, where the men pose as Palestinian refugees.

As Friedman writes, “In retrospect, we understand that our men had found their way into one of the only corners of the Zionist movement where their identity was valued.” Double identity, he argues convincingly, has always been a part of life for Jews. But particularly for Arab Jews.

“That was their secret weapon,” Friedman says in the interview. “The people who set up the Arab Section were British, and they understand that ethnic impersonation is impossible. A lot of British officers had been undercover in Greece during the war; they could fool the Germans, but never fool the Greeks. That was really hard to pull off! But the Jews in Palestine offered this incredible opportunity. Jews had people who could pass for anything you want: Polish, German, Arab — because Jews had these double identities. That’s what makes them such good spies, and explains the success of Israeli intelligence in the early years of the state.”

Yet they refused to call themselves agents or spies, Friedman explains.

“Instead, they chose a peculiar word, one that exists in Hebrew and Arabic but has no parallel in English. The word, mista’arvimin Hebrew, or musta’aribinin Arabic, translates as ‘ones who become like Arabs,'” he says.

“Mista’arvim comes from something much deeper. It is actually rooted in the lives of Jews in Arab countries. In Aleppo, for example, there are two Jewish communities. One calls itself Sephardic, the Sephardim, they were expelled from Spain in 1492. And the second one has always been in Aleppo; before Islam, before Christianity. They adopt Arabic, and Arabic culture: mista’arvim.”

The term is still used today in Israel. (Friedman points to “Fauda,” the hit Israeli TV show available on Netflix, where the Arabic-speaking undercover commandos are the perfect example of modern-day mista’arvim.)

As we follow their story, from training to exploits undercover to their return to Israel, we get to know the four men. Gamliel, from Damascus, was the first agent sent abroad and poses as a store owner in Beirut. Yakuba, the only one of the four born in Jerusalem, was “fiery and resistant to discipline.” Havakuk, from Yemen, dies at age 24; Friedman dedicates the book to him.

And there’s Isaac, whom we get to know the best. We learn about Isaac’s complex relationship with Georgette, a local girl in Beirut; and about his training; and about his return to Israel in 1950. One passage is particularly striking — about Isaac recalling the Muslim ritual washing, or wudu.

“All of this was so deeply in Isaac’s mind that he could go through the wudu for me in his kitchen seventy years later — hands, mouth, nostrils, face — and then begin the prayers, as if he’d been at mosque that morning,” Friedman writes.

Friedman points out they didn’t go to spy school and had very rudimentary training — there was no Mossad, no state and the Arab Section was “very ad hoc.” Friedman writes about how the men learned Muslim prayers, the local figures of speech, and how they practiced in Arab markets in mixed cities like Jerusalem and Haifa.

“It’s hard to remember, from 2019, how improvised and chaotic [it all was]. No one knew the state was going to be founded in 1948. One thing I love about the story,” Friedman says, “is the unpreparedness. They were winging it!”

And because they were winging it, the story takes a darker turn: half of the Arab Section was caught and executed.

Friedman believes “Spies of No Country” is the “anti-Mossad story.” Why?

“In the world of spy mythology, there is some great operation that shifts the course of events,” he says. “In the real world, spies don’t understand what is going on. They’re very flawed characters moving in the shadows, and their role in the events is ambiguous. [It’s] not like they blow something up and the war changes.”

The Arab Section men were “a lot of young guys who don’t know what they’re doing,” which Friedman believes is a more authentic spy story than what people are led to believe by pop culture.

But that doesn’t mean Friedman doesn’t love classic spy stories: His favorite is John le Carre’s “Tinker Tailer Soldier Spy,” because it is “an incredible spy novel with a complicated plot that fits together perfectly.”

Overall, Friedman hopes people take away one fundamental idea from “Spies of No Country”: To understand Israel, we must think of it as a Middle Eastern country.

“We still come to Israel with these very European stories to understand its formation,” like that of Theodor Herzl, the kibbutzim or the Holocaust, “but they don’t explain Israel in 2019. You won’t get very far with these old stories because half of Jews come from the Islamic world. If we want to understand Israel, we have to distance ourselves from stories about Europe.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.