(JTA) — An unlikely player recently joined the public fight against erasing women from the haredi Orthodox media. That player is the multinational furniture company Ikea – and, unfortunately, it’s playing for the wrong side.

In recent years, Ikea has distributed annual catalogs to most neighborhoods in Israel. Aside from being written in Hebrew, they look similar to catalogs in other countries and contain pictures of both men and women. In 2017, however, Ikea prepared an additional catalog targeted to the haredi population and distributed in haredi neighborhoods – a catalog entirely devoid of women.

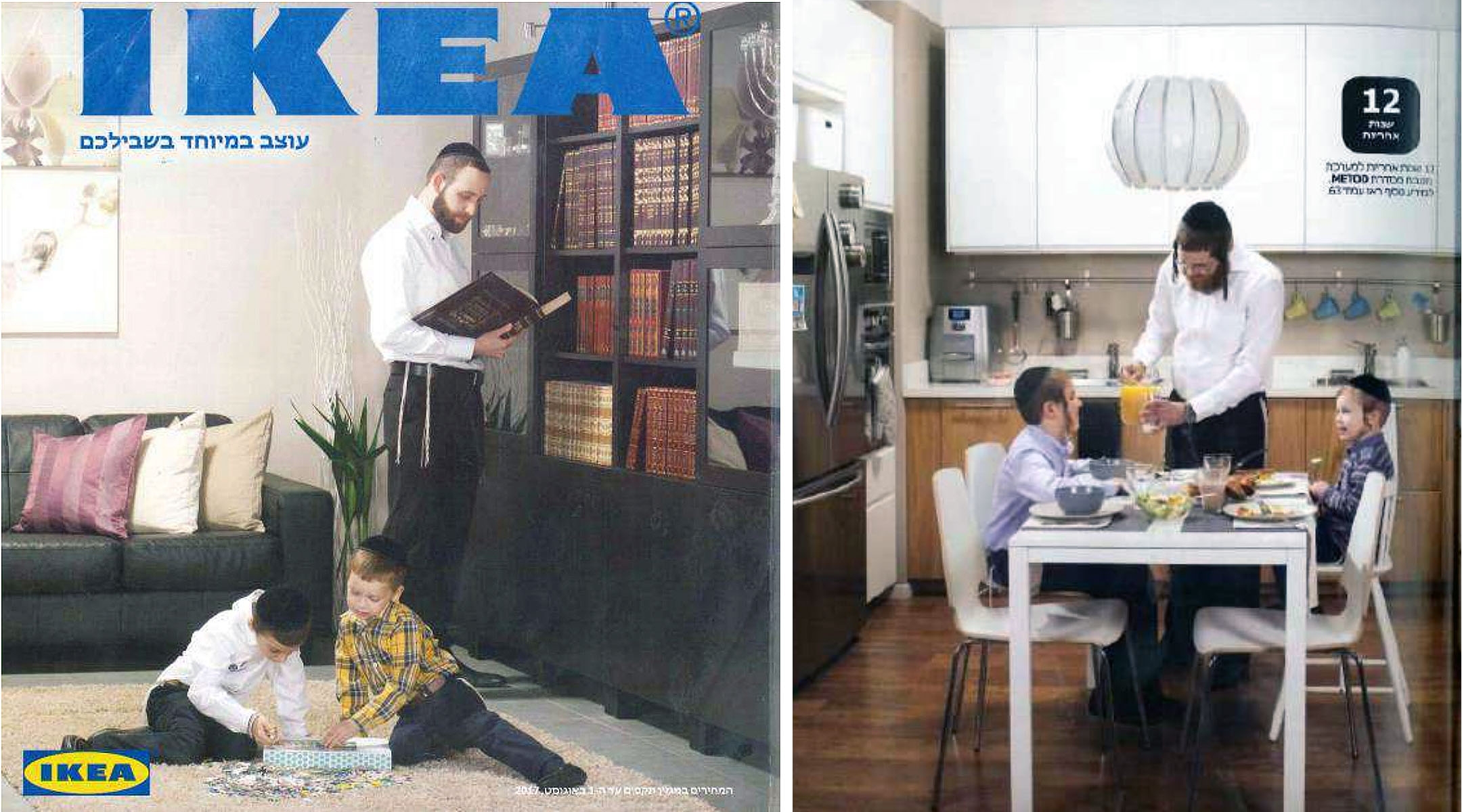

Ikea’s catalog for haredim contains language and products geared to the sector’s needs, such as extra hanging space for men’s shirts and large bookcases for storing volumes of the Talmud. It also includes images of haredi men and boys eating at a stylishly set kitchen table, reading and playing a game. One can only imagine that the women and girls who prepared the food disappeared when the men and boys came to eat.

In the past, Israeli haredim have objected to images of women who were immodestly dressed. Haredi publications would feature photos of women, including the wives of notable figures like the Lubavitcher rebbe. But in the last 10-20 years, more and more newspapers serving the haredi population have expunged pictures of women and girls of any age, in any dress, including world leaders like Angela Merkel and Israeli Cabinet members.

Examples include not just periodicals, but obstetrics clinics refusing to put up images of female patients or staff. Events targeted to women involving female speakers are often publicized without pictures. Girls’ faces are often blurred or cropped, even if their bodies are shown.

By publishing catalogs without women, Ikea has succumbed to this disturbing phenomenon.

Haredim represent about 20 percent of the Israeli market, but my legal team and I maintain that the majority do not advocate for the erasure of women. Editing females out of pictures does not represent a traditional religious value or concept. And it’s safe to say that Ikea as a company doesn’t see women’s pictures as immodest.

How ironic that a catalog intending to be more “religious” makes a mockery of Jewish family life. Ikea easily could have chosen to include modestly dressed haredi women.

Following an uproar, Ikea apologized for the discriminatory catalog. Yet a year later, the company again distributed a catalog tailored to haredim – this time eerily containing no pictures of people at all.

A common response to charges of discrimination is to make a new rule that supposedly applies to everyone, like when some southern U.S. municipalities shuttered their public pools altogether rather than allowing in black students in the 1950s. The newer Ikea catalog for haredim follows this model: It doesn’t address the root problem and still erases women.

On a practical and economic level, policies prohibiting women’s images harm women. Whether it’s small business owners who can’t effectively market their products or a speaker whose photo doesn’t appear in a conference program, individual women suffer when these policies are in place.

But the greater harm is on a societal level. The practice of erasing women leads both girls and boys to view women and girls as excluded from normal life – secondary at best, at worst nonexistent.

The action taken by Ikea wasn’t just discriminatory: It was illegal. Israeli law prohibits companies from discriminating on the basis of gender when offering a product or service.

As the sole plaintiff in a new class-action lawsuit, I am represented by the Israeli Religious Action Center and advocate Assaf Pink, who successfully sued the religious radio station Kol Berama over its lack of female presenters. The court ruled that both presenters and listeners were harmed by the practice and awarded damages to the plaintiffs in the class-action suit.

According to an independent survey commissioned by my counsel, 19 percent of the women who remembered receiving the catalog were frustrated, angry or otherwise distressed by the lack of women’s pictures. We are asking for compensation of at least 1,500 shekels ($415) for each of the estimated 10,000 women who experienced this distress, based on the survey and the approximate number of households receiving the catalog.

While I identify as Modern Orthodox, extreme attitudes have a way of seeping into more moderate communities like mine. Indeed, in recent years, women-free ads are sometimes found in religious Zionist publications or ads targeting our community.

Many men and women in the haredi population object to these extreme policies.

In Israeli class-action suits where the plaintiffs cannot all be identified, the funds awarded are deposited into an account maintained by the court. This money will then be disbursed among women’s rights organizations. We are also asking for a new catalog, containing pictures of both males and females, to be distributed in the relevant areas.

While going to court will likely be a long process, the lawsuit’s ultimate success will send a powerful message that erasure of women will not be tolerated.

Ikea, a company that claims to value equality, has cooperated with haredi extremists to trample on half of the population. It has done so not because of any ideal, but solely in order to sell more products. As a powerful international company, Ikea should not be paving the way for more discrimination. Rather, it (and we) should be working toward a more equitable society in which all women, religious or not, are treated and viewed as equal members of society.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.