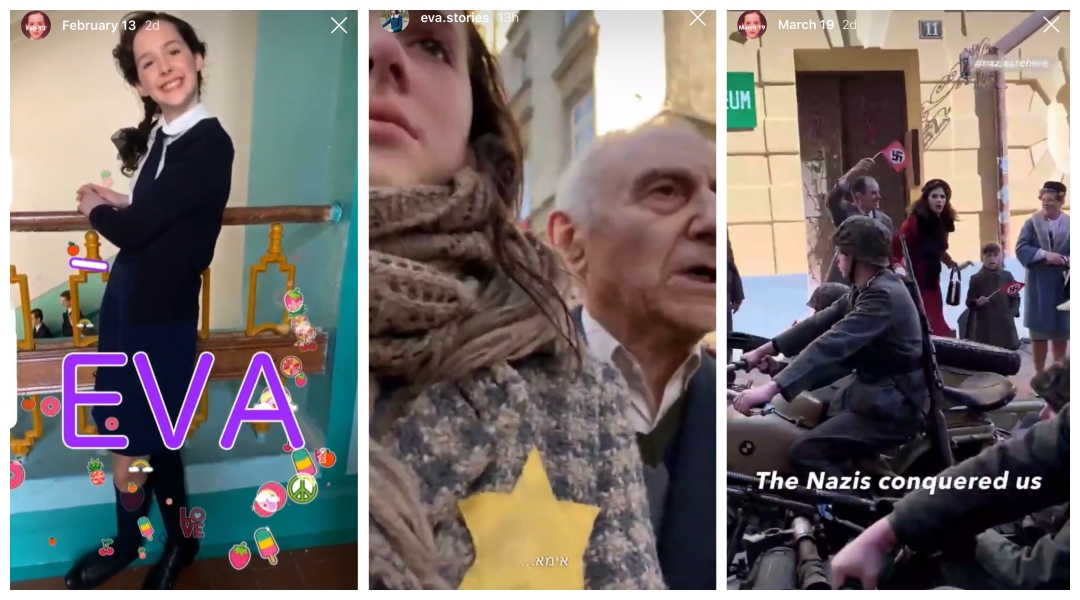

(JTA) — Eva Heyman is an energetic 13-year-old Jewish girl with a bright smile. Go to her Instagram page and you’ll see selfies of the brown-haired teen with her best friends, videos she filmed while bored at school and her gushing about her crush, a classmate named Pista.

But the girl on the Instagram page, which now has 1.3 million followers, isn’t really Eva.

Eva Heyman was killed in 1944 in Auschwitz, and she is being portrayed by an actress as part of a project by an Israeli tech executive and his daughter. For 24 hours on Yom Hashoah, Mati and Maya Kochavi put up a dramatized version of Eva’s life on the social media site called Eva.Stories. The stories are based on a diary kept by Eva prior to her deportation and death.

The Kochavis had hoped their initiative would help spread awareness about Eva’s life and the Holocaust. Their effort, however, sparked some controversy.

Yuval Mendelson, a civics teacher and musician, called it “a display of bad taste” in a column for Haaretz prior to the project’s launch.

“[A] fictitious Instagram account of a girl murdered in the Holocaust is not and cannot be a legitimate way” to educate young people about the Shoah, he wrote.

The initiative speaks to a larger conversation in the Jewish community and beyond on the future of Holocaust testimony. With most survivors now in their 80s and 90s, Holocaust remembrance organizations are seeking new ways to tell the story to future generations that will never get to meet those personally impacted by the Shoah. Last year, the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center became the first to permanently showcase a new exhibit that allows visitors to interact with holograms of survivors.

“We have to think of more creative and stronger ways to convey the horrors of the Holocaust to the newer generation that won’t have the chance to speak to a survivor,” Maya Kochavi, 27, told CNN.

In real life, Eva Heyman was the only child of a Hungarian Jewish couple, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and after their divorce was raised largely by her grandparents. In 1944, she and her grandparents were forced into the Jewish ghetto in Oradea. Eva was deported to Auschwitz that June and died there on Oct. 17 of that year.

When I first learned about Eva.Stories, I was skeptical. I found the first few episodes strangely lighthearted for a project on the Holocaust, with the main character dancing, smiling and posting emoji-filled selfies. The actors’ accents also aren’t consistent, and the conceit that social media existed 80 years ago threatens to undermine the veracity of the real-life story.

But as the story continued, I found myself warming up to it. The project not only educates about the history but affectingly shows how events would have felt for a 13-year-old. As the Nazis march through the city, we see Eva running to her frightened mother, the camera shaking. When her mother tells Eva that she has to wear a yellow star on her coat, the teen at first refuses. She doesn’t want to look different and worries that people will make fun of her.

At the end of the story, as Eva is loaded onto a train cart to Auschwitz, we see the young girl panicking and on the verge of a breakdown. I struggled to hold back the tears.

At 27, however, I may be a bit older than the target audience, so I spoke to a few teenagers and early 20-somethings.

Gavi Altman, a 14-year-old living in Israel, told me the project was a hit among her friends.

“In our class, everybody was hyped up about when it was going to come out,” she said.

Altman, who asked that her exact location not be used here, said the project helped her feel connected to the Holocaust in a way she never had through lessons in school.

“They’re trying to make it that our generation can relate somehow,” she said. “When somebody just tells you the story, then you’re just thinking ‘Oh, it’s from such a long time ago, it has nothing to do with me.’ I feel like this makes you feel more connected to it.”

Eliana Silver, a 19-year-old student at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, Scotland, also found the stories compelling.

“It’s a very real way of seeing,” she said, “because obviously when we watch pictures and videos from those times, you kind of just see it from an outsider perspective. But now it’s like you’re there with the characters. It gave me chills.”

Rachel Fadem, an 18-year-old living in Chicago, thinks the project could serve as a way to engage those who otherwise may not be interested in learning about the Holocaust. But she worries how viewers who aren’t knowledgeable about the Holocaust may see it.

“I’m just a bit wary of how some people might take it lightly,” she said.

Aliza Nussbaum Cohen, 20, a freshman at Clark University at Worcester, Massachussetts, also has trepidation about the project.

“The fact that it’s on social media, side by side to such nonsense, and such unnecessary and meaningless content, I feel like that can lead to this also being meaningless in some way,” she said.

Nussbaum Cohen, the daughter of JTA contributor Debra Nussbaum Cohen, also questioned whether Eva.Stories would actually have an impact.

“To know that they put so much money into something that could’ve been spent on Holocaust education in schools or something like that, that’s what hurts me the most about it,” she said.

But Altman isn’t too concerned with those who weren’t fans of the project.

“Maybe people who won’t like it will hate on it,” she said, “but that’s like with everything.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.