JERUSALEM (JTA) — On the first day that Israel’s schools reopened nine weeks after closing to stop the spread of the coronavirus, Kalanit Taub’s 8-year-old daughter stayed home.

As a third-grader, her classes were among the first wave of those to resume. But her 10-year-old brother’s classes hadn’t yet resumed, and Taub was recalling how both children had been exposed to the virus at school back in March.

“If there is another exposure, what will we do?” she asked. “My husband and I are back to working at our workplace. Can we put the whole family in quarantine again? That would be hard. Can we put an 8-year-old by herself in a room for a week or longer while she is quarantined? If she gets sick, who would take care of her?”

Taub was not the only Israeli wrestling with these questions as their country began, with just two days’ notice, to open its schools in phases last week. On May 3, the first day of classes, just 60% of eligible students attended, entire cities kept their schools shut and open schools followed a patchwork of policies aimed at keeping students safe. Ten days later, more than a dozen cities have rejected instructions to bring more students back to class.

Israel’s experience underscores the logistical challenges that countries around the world face as they work to get their school systems operational once again.

Given what’s known about COVID-19 and about children’s learning, “the balance is very clear in favor of opening,” said Dr. Hagai Levine, an epidemiologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the head of the Israel Association of Public Health Physicians.

“Unfortunately, in Israel, the decision on opening of the schools was not handled very well,” he added. “This got the entire system confused.”

Virtually all students around the world saw their schools close this spring as the pandemic descended. In some places, including in affluent areas of Israel, students continued learning virtually, as their schools and teachers hastily retrofitted their lesson plans for online instruction. But many children, especially those in families and communities with fewer resources, have had little to no real instruction or social interaction in weeks. Meanwhile, their parents cannot return to work without a place to send their children during the day.

That makes reopening schools a crucial task — with clear benefits but also obvious risks as children and teachers begin gathering again. While children represent only a tiny fraction of confirmed coronavirus cases, exactly how vulnerable they are to the disease and how readily they can spread it remain unclear.

Some countries are reopening preschools first in an attempt to provide child care that might allow parents to return to work. Others are starting with older children who are more able to follow social distancing rules and have less time to recover from interrupted schooling.

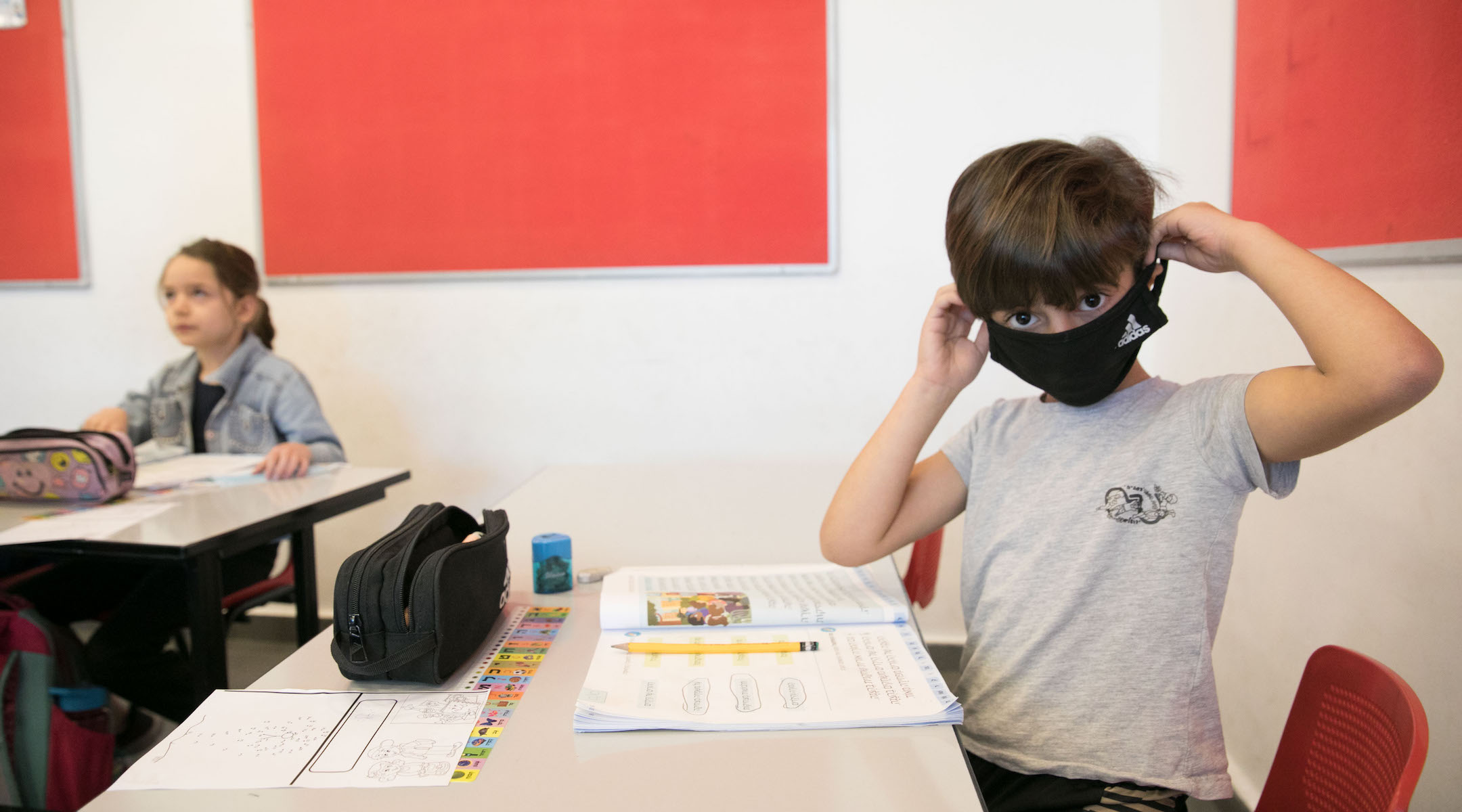

Israeli first- to third-graders social distance and bring doctor’s notes at the entrance to their Jerusalem school, May 3, 2020. (Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90)

Israel began with both extremes, inviting students in first through third grades and the final two years of high school to return May 3. (The haredi Orthodox school system, which educates nearly 25% of Jewish elementary school students, started with grades 7-10.) This week, day care centers, preschools and kindergartens reopened to serve children up to age 6. And with infections continuing to fall in the country, the government is pressing to reopen the rest of the grades next week.

Many changes are visible: Classes are capped at 15 students, about half their size before the pandemic, and run for just five hours a day, down from six or more depending on the school. In the interim, the newly separated classes are using empty classrooms usually used by older grades. Children older than 7 are required to wear masks at school.

But the reopening has had its share of road bumps. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced on a Friday that schools would reopen less than 48 hours later, on Sunday, giving only the weekend to prepare. Leaders of several cities initially said they could not or would not comply.

Tel Aviv’s mayor, Ron Huldai, said he would not “go by rules set by people who do not act responsibly” and delayed reopening the city’s schools. Other cities, including Ashdod, Haifa and the haredi town of Bnai Brak, which has been hit especially hard by the pandemic, also kept their schools closed at first.

Meanwhile, schools raced to accommodate rapidly changing rules. In a recording obtained by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the administrator of one school near Jerusalem apologized to parents, saying that he had been receiving new instructions almost every hour the evening before classes were set to resume and still was unsure what would happen in the morning.

“You can’t just turn on the faucet. You have to organize the school, disinfect the building, organize small groups, prepare lesson plans,” a teacher at one Israeli school complained to Haaretz, an Israeli newspaper. “The most talented principal can’t do all this in the time allotted.”

Health and education officials said the reopening plan was devised as carefully as possible under the circumstances. Officials reviewed emerging research, conducted an epidemiological study of Israeli families and coordinated across government offices, according to Dr. Efrat Aflalo, a representative of the Health Ministry.

“We didn’t feel unprepared for the decision,” Aflalo said. “Decisions were made based on what was going on in the world and Israel.”

But different government offices didn’t always have the same information as the country was “trying to adjust new methods of studying in schools in a very short time,” said Dalit Atrakchi, an Education Ministry official.

“It’s unclear all over the world,” she added.

Some parents say they are confident about the changes at their children’s schools.

“I sent my first-grader back,” said Gila Radinsky Gildin, a resident of Beit Shemesh, a bedroom community between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. “They check temperatures as she enters the gate of the school. [Her] class is split into two and between both classes only about 12 girls come.”

A teacher checks the temperature of a student at a haredi Orthodox school in Jerusalem, May 6, 2020. (Nati Shohat/Flash90)

In Modiin, Rebecca Shapiro-Chelsky said her son’s school staggered the arrival and dismissal times for students, so only a few children and parents are in the same space at the same time.

“My son has told me that they don’t leave their classroom the whole time, so he’s not with any other kids except the ones in his class,” Shapiro-Chelsky said.

But at another school in the same city, families were having a different experience. Speaking last week, Chaya Rosen said her children’s school had all the students arrive and leave at the same time, causing congestion at the gates. She has kept her children home.

“We’re waiting to see what happens now that everything is reopening,” Rosen said. “I think the government’s guidelines are fine for the most part, but it felt very rushed and unstable that the return to school was decided Friday afternoon for a Sunday opening. Adults don’t keep 2 meters [6 feet] away, so I don’t see how kids will be able to.”

And while children with a fever are barred from coming to school, the schools have discretion over whether they actually take students’ temperatures at the door, as is required in some countries.

Chedva Tennenberg, a teacher in Jerusalem, said she and other educators could not get clear answers to their questions during an online meeting two days before their school reopened. She also was surprised by the procedures in place to make sure that only healthy children came to class.

“I had to get my temperature checked twice to walk into Bezeq,” Tennenberg said, referring to an Israeli phone company. “But for schools — parents had to sign a note that they took the kid’s temperature. Many kids said no one took their temperature.”

In at least one case, a student who had been diagnosed with the coronavirus attended a haredi elementary school for children with special needs, forcing it to close temporarily, Yeshiva World News reported.

Face masks are exempted for first-graders. (Olivier Fitoussi/Flash90)

For now, classes are optional, so students don’t face penalties if they stay home. But soon, the parents of older students will have to make a similar decision, with the government pushing to continue rebooting the school system on Sunday.

To facilitate distancing in classrooms, students will attend only for one to three days a week, learning online the rest of the time, under the government’s proposal.

But even with the number of cases in the country continuing to decline, many are apprehensive. On Tuesday, 15 cities across the country rejected the expansion, including several, like Tel Aviv, that had previously objected to the government’s hurried reopening of grades 1-3.

As for Taub, she said she is inclined to wait quite a while before sending her children back to school. Even once all grades resume their studies, she said, she plans to wait until “time has passed and I don’t see a spike in cases.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.