This story originally appeared on Kveller.

In the 1880s, a Black Baptist and a Reform Jewish family lived in the town of Tyler, Texas. In the 1870s, Tyler was an ill-fated town with a train that ran right through it. When an unlikely stop was created on the line in the 1880s, Tyler emerged as a commercial center of West Texas.

The Jewish family’s patriarch, Maurice Faber, came from an unbroken line of Orthodox rabbis. He believed his religion was ready to be more progressive, however, and in the 1880s he moved his family from Hungary to the U.S., eventually becoming a Reform rabbi in the Texas town. The train line had tripled the town’s population within the decade, and opportunities for businesses continued to grow.

Meanwhile, in 1897, Thomas Butler was born to a land-owning Black Baptist family in Tyler. He became a foreman on the railroad and a father to 13 children, all of whom attended an all-Black school in the segregated town. In the 1910s, Butler and his family left Tyler in the middle of the night after his white supervisor made advances on his wife.

These two families lived only miles away from each other, though they may as well have been worlds apart. But both families, in their own way, taught their children — and their children’s children — to lead a life of justice (tzedek) and healing the world (tikkun olam). Both families knew communities working together was not enough to desegregate the town. The Butlers preached on getting an education, working together and being good to others. The Fabers sermonized to push communities forward, to take action and to do their part to ensure tomorrow will be better than today.

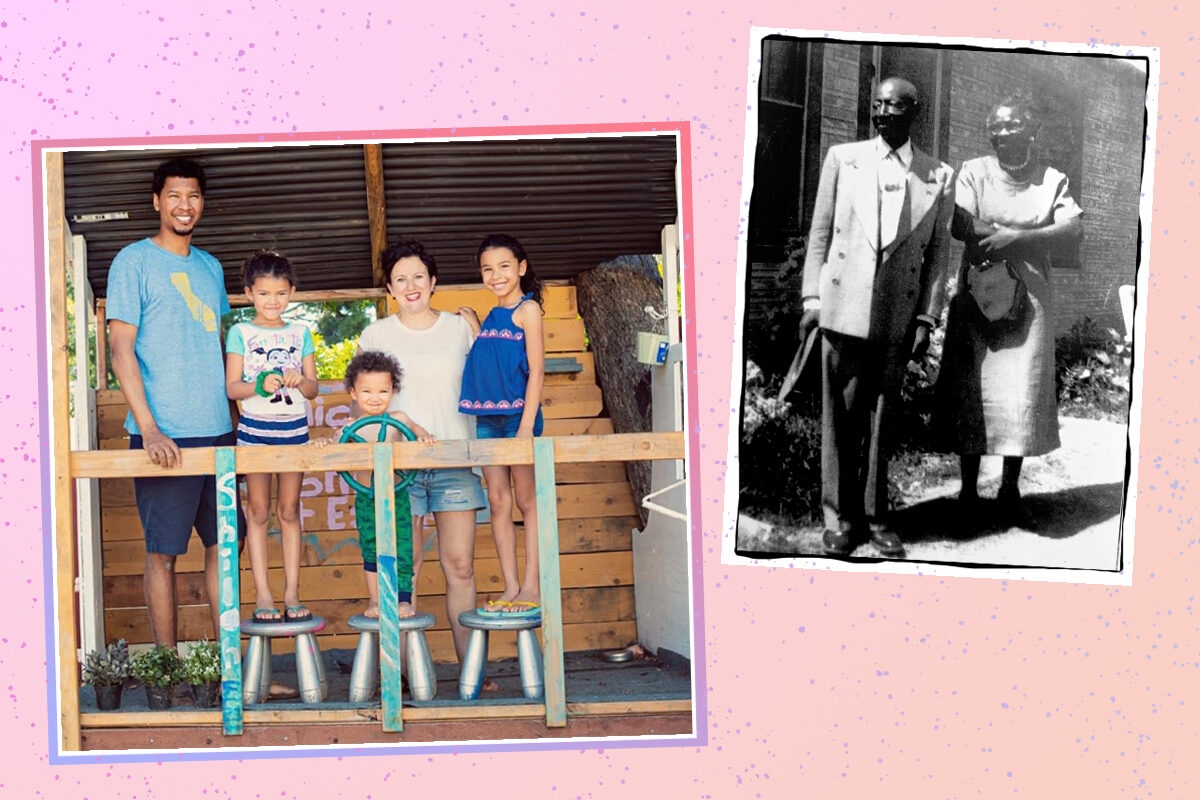

Nearly 150 years later, the descendants of these families met and fell in love in San Diego. I’m the great-great-granddaughter of the rabbi, and when I met Anthony (the great-grandson of Thomas Butler), I knew he was my bashert, my soulmate.

Our families became officially interwoven in October 2009 when Tony and I married. Even today, interfaith marriages are only performed by a handful of rabbis — indeed, interracial marriages only became legalized in this country in 1967 — and we married under a chuppah. Rabbi Harry Danziger officiated the traditional Jewish ceremony, as he had my parents’ and my sister’s weddings, as well as my grandfather’s bar mitzvah at the age of 75 and his funeral at 76.

Tony and I are raising our families’ first generation of Black Jews. We have two daughters, ages 8 and 5, and a 2-year-old son. We live in San Diego, and we intentionally moved to a pocket of the city where our kids see diversity in the families in our neighborhood: homes with two dads, two moms, a single mom, a single dad, biracial, multiracial and various socioeconomic statuses. While our temple is rather small, our children are not the only Black Jews.

The recent senseless deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor have ignited a much-needed call to action in the U.S.

Our families — with histories of persecution on both sides — have long been prepared for this moment. Over the years, we’ve been steeping our children in the following lessons, drawing upon the generations before us. The following foundations ground our children in fortifying their Black and Jewish identity:

1. Step out. It is not enough to safely stay within the bubble of our neighborhood. When we travel, we often get a few extra glances. We try to teach our children how to be — and be themselves — in uncomfortable spaces. Often that means experiencing the awkward exchanges with strangers. Many times it’s people approaching us to say how unique and beautiful our family is.

2. Be who you are. Our children’s identity is unique. However, when there is a Hebrew school performance, both sets of grandparents sit in the front row, demonstrating that being Black is not separate from being Jewish.

3. Don’t be pushed out. Embrace standing out in a room and demonstrating that there is space for everyone. Christmas and Easter continue to be celebrated in their secular public schools — my girls are the only Jews in their classrooms. While they understand how decorating a gingerbread house allows them to help others celebrate their holidays, we make sure there’s also a Jewish activity for them to share with friends that teaches the traditions of their Jewish family.

4. Speak up. It is not enough for my kids to just speak up for themselves. It is not enough for the Black community to be the only advocates for their community. Likewise, it is not enough for Jews to champion only Jewish causes. My kids, like so many of us, are learning through the news that it takes allies of communities to help make change. Their voices must be used to amplify those that aren’t heard.

5. Acknowledge the road was paved. My children stand today on a path that was built by their ancestors. It was not so long ago that interracial marriage was illegal — we wouldn’t be able to be a family if it weren’t for the people who fought for change. It is our turn to make space for communities that are on the same journey.

These days, many parents are sitting down with their children to discuss racism, and rightly so. Our families, by contrast, have spent generations standing up for what is right. Our children are the future, and they’re now carrying the lessons of their ancestors during this critical period of civil unrest amid a pandemic.

But if our kids ever need a reminder of where they came from, there’s an easy solution: Just a few miles away lives a set of grandparents from the Butler and Faber sides. These four wonderful adults, steeped in the same discourse, all remind them that history is only as far away as they make it.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.