(JTA) — Israeli poetry scholar Rachel Korazim had been thinking about cutting back on travel when the coronavirus pandemic made the decision for her.

“I said I really want to shift my teaching to distance learning because, you know, I’m not getting any younger. Travel is tiring,” she said she had told her husband.

But Korazim soon realized that her regular appointments at two leading destinations for adult learning, the Pardes Institute for Jewish Studies and the Shalom Hartman Institute, would not happen and felt disappointed.

Then one morning in March, a viral video popped up on her phone of Italians — then facing a steep death toll — singing from their balconies. Korazim felt inspired.

Playing on the fact that the Hebrew word for song is the same as for poem, she posted on Facebook, “I cannot sing like the Italians do, but I can teach poetry.” She invited her followers to join her for a Zoom session that evening covering Jewish women’s voices in literature.

Within days, more than 200 people were tuning in for Korazim’s nightly poetry classes. Her experience offered an early indicator of what thus far has been a lasting phenomenon during the pandemic: Craving connection and with time on their hands, Jews have been attending online courses with intense devotion. And rather than experiencing a surge of interest in the pandemic’s early days, then waning as people adjust to the new normal, online learning in the Jewish community is expanding.

Perhaps the most salient example is the Hartman Institute’s summer program, where Korazim usually teaches in Jerusalem to about 150 people who work in synagogues and other Jewish institutions. She had expected not to have anything to participate in this year, but instead an online symposium has drawn thousands from around the world, many with no professional Jewish affiliation but a deep and abiding interest in learning.

“Our mission is to develop the best ideas from the past,” said Dan Friedman, the Hartman Institute’s director of content and communications. “Sadly the Jewish people over thousands of years have had plenty of chances to think about crisis and how we deal with it, so how do we get the best ideas we have and think about how they’re relevant to our current state of things? And how do we get those ideas to places where it will make a difference?”

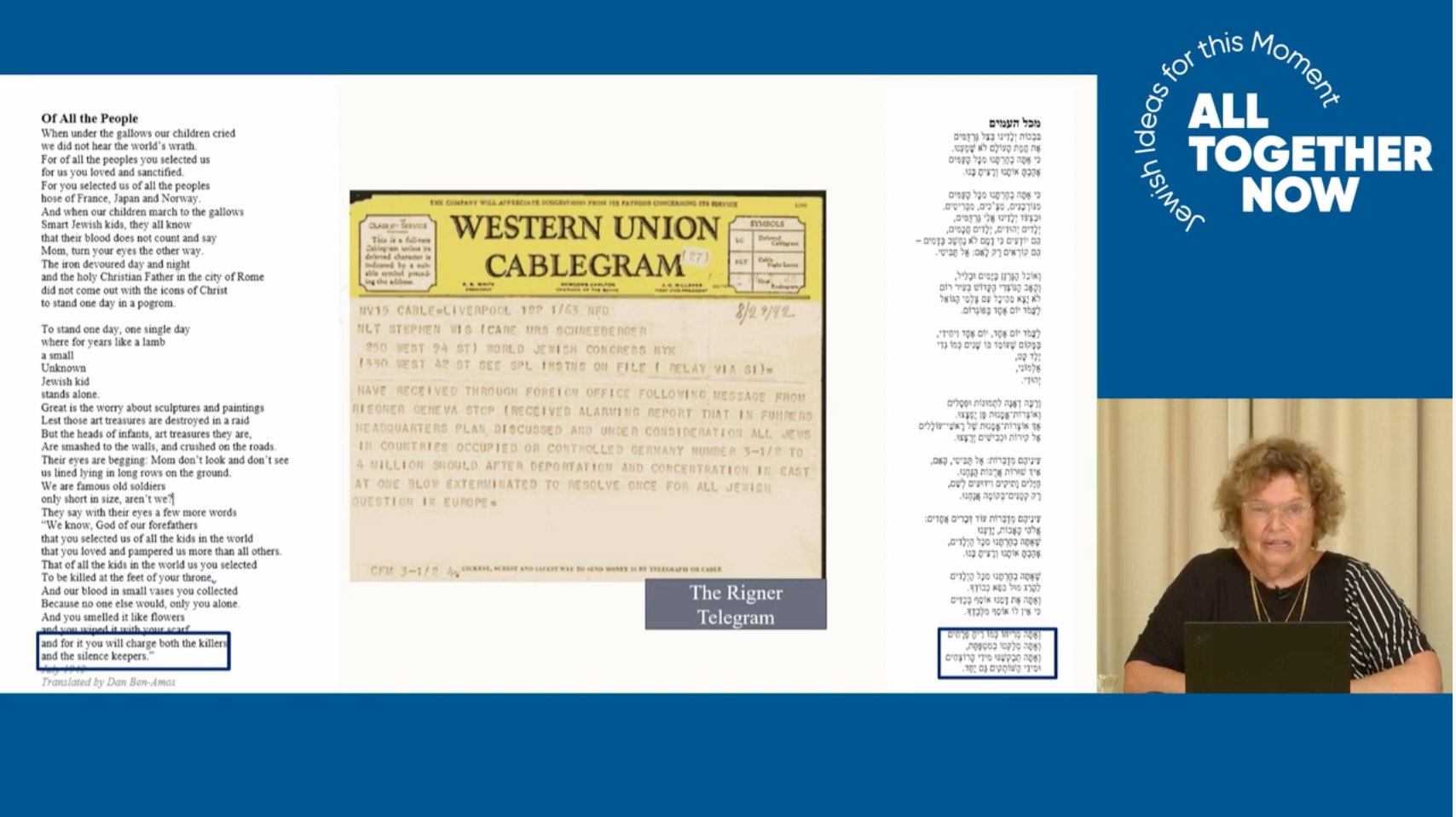

The answer, concluded Friedman and his team, led by Hartman’s president, Yehuda Kurtzer, was a monthlong online program called “All Together Now: Jewish Ideas for this Moment.” Assembled in less than six weeks and free for participants, the program drew over 1,000 signups on the first day it was announced in June. By the end of the first week, more than 6,000 people, including some 1,100 rabbis and 600 Jewish community professionals, had registered for talks and workshops from prominent thinkers, religious leaders and artists like Korazim.

This week, the last of the series, the institute is adding opportunities for participants to talk to each other, too.

“The thought was we can’t bring people to the ‘mechon,'” Friedman said, using the Hebrew word for an educational institution, “so let’s bring the mechon to the people.”

While Hartman’s program is free, even programs charging a fee are seeing significant and sustained interest. The Pardes Institute, also located in Jerusalem, moved its summer learning program online and set an enrollment fee of $175 for a 10-day session and $145 for an eight-day session.

“We were very nervous about doing an online summer program and charging for it,” acknowledged Alex Israel, the institute’s programming director. “We thought to ourselves, will people pay? Because there’s so much going on for free online.”

The answer was yes. Over 250 people have paid for courses during two summer sessions, more than twice the number who attended in-person classes last year. They include older adults who might not have attended in person but have said that the online courses offer a lifeline during a time of isolation, Israel said.

“Our business is about teaching people text, and teaching skills, and we said we think we have a good enough name that we are the text people, we are the experts at teaching serious but relevant Torah, and we think people will pay for it if we put together a robust enough program,” he said. “And we’ve been proven correct.”

Hartman and Pardes are among the biggest names in Jewish learning. But other organizations also are encountering surprising interest in their online offerings.

A conference for educators called NEW-CAJE drew more than 900 participants, double the typical in-person number, for a month of sessions about innovation in Jewish education.

My Jewish Learning, the nondenominational educational website, launched live classes for the first time, offering dozens of virtual classes on topics ranging from holidays to theology to basic Hebrew. (My Jewish Learning, like the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, is part of 70 Faces Media.) Thousands of people joined in.

And the Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America, which typically offers resources on Sephardic Jewish learning, as well as scholarships and community celebrations, has a pandemic-inspired “digital academy” presenting classes like Ladino 101 and text study through the Sephardic lens.

That wouldn’t have been possible through live events, said Ethan Marcus, the group’s communications director.

“This has been a moonshot in more ways than one, just connecting people really spread out across the world,” he said. “We have participants in Turkey, in France, in Argentina — we even had a participant in Japan. It’s really elevated our profile.

“But more importantly it really made us rethink what it means to be a national community, how do we play a role in people’s lives daily today.”

With the pandemic wearing on and old expectations about in-person contact becoming a memory, the likelihood exists that the shift to online learning will endure even after travel and gatherings become safe again.

“I think that probably our direction of change will be mirrored by the Jewish community,” Friedman said. “There will be a lot more hybrid in-person and online institutions, organizations and movements. I think that we’ve seen the vast economic effects that [the pandemic] will have, and that will probably lead to a number of different organizations working together in ways that have been unprecedented until now. I think there will be an acceleration of change.”

Indeed, more than 90% of the respondents to surveys about My Jewish Learning’s online courses said they would continue to take them after the pandemic ends, and three-quarters said they felt they had gotten as much out of the classes as they would have in person.

For Korazim, this summer’s experience has resolved one concern she had about teaching online: whether her students could experience the same esprit de corps that she has seen take hold when they are in the same room.

“I now have a community,” Korazim said. “I come into class 20 minutes before, and people are talking about their flooded basement, or their crumbling bridge that needs to be closed, because they are suffering. … My class is where they get to talk to adults.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.