(JTA) — Fania Records, often called the “Motown of Latin Music,” announced the passing of Larry Harlow on social media last week. Once the record label broke the news on Aug. 20, a who’s who of Latin music offered tributes.

“Larry’s contributions to what today is known as salsa are immense,” seven-time Grammy nominee Bobby Sanabria wrote on Facebook. “A true part of NYC’s history has been lost […] to our Latino community and it is heartfelt.”

But Harlow, whose paternal grandfather was the theater critic for The Jewish Daily Forward, was neither Latino, nor did he have Latin American roots. In a nod to his heritage, he was known in the Latin music world and beyond as “El Judio Maravilloso,” “The Marvelous Jew.”

Harlow did come from a family of musicians. His father, Nathan Kahn, was a bass player of Austrian descent, and his mother, Rose, an opera singer, had Russian roots. Born in 1939 as Lawrence Ira Kahn, he grew up in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn. The name Harlow is a derivation of his father’s stage name.

“My father got in a car accident and nearly died,” he told me in 2010. “The doctor on the scene saved his life.”

The doctor’s name was Harlowe, and to honor him Kahn took on the stage name Buddy Harlowe. Larry Harlow would drop the “e” for his stage name on his way to becoming one of the most respected musicians on the Latin scene.

For three decades Buddy Harlowe led the house band at the legendary Latin Quarter nightclub in Manhattan, and Larry spent hours backstage with the daughter of owner Lou Walters.

“When I was a kid, 10 or 11 years old, Barbara and I used to sit in the booth next to the spotlight and we saw every show that came in there,” Harlow recalled in a New York Times interview.

Barbara, of course, would become the famed Jewish journalist Barbara Walters.

Harlow started piano lessons at age 5, later excelled playing various instruments and was accepted to the then prestigious High School of Music and Arts in Harlem. There he discovered the music that would become his life.

“When I got out of the subway, I would walk up this huge hill and hear this strange music coming from all the bodegas,” Harlow told the Forward in a 2006 interview. “I thought, ‘What kind of music is this? It’s really nice.’”

Harlow allegedly used his bar mitzvah money to buy a reel-to-reel recorder and one-way ticket to Cuba in the 1950s to study the music scene. He traveled the country by bus, accompanying musicians, learning Spanish, attending Santeria ceremonies, immersing himself in Cuban culture. At Fania, a popular luncheonette in Havana, he met a fellow New Yorker who shared his passion for Latin music.

Jerry Masucci, the son of Italian immigrants, would years later become the co-founder of the influential Fania Records.

“He was from Brooklyn like me, so we hit it off,” Harlow said.

The Cuban Revolution cut short Harlow’s trip. Back in New York, his mother arranged for him to play in the resort hotels popular with Jews in the Catskills region of upstate New York. Prior to the revolution, Cuba had been a very popular vacation destination for more affluent Americans who brought cha-cha, mambo and rumba music back with them to North America. Not everyone could afford a trip to the island, but the music could transport them there.

Cuban music became a staple in many of the resort hotels of the so-called Borscht Belt, which employed dance instructors and mambo bands. Tito Puente played at Grossinger’s. And there was the popular Irving Fields Trio, whose best-known work, “Bagels & Bongos,” combined Jewish (often Yiddish) songs like “My Yiddishe Momme” (“My Jewish Mother”) with Latin rhythms.

At Schenk’s Paramount Hotel, the musicians would get together for jam sessions. That’s where Harlow met many of the future superstars of Latin music.

After the United States imposed trade and travel embargoes on Cuba, major music labels dropped many of their Latin American artists. Masucci, then a divorce attorney, would soon fill the vacuum. In 1964, he and the Dominican-born musician Johnny Pacheco founded Fania Records, named for the Havana diner.

Larry Harlow was their first artist signing.

“The first thing I noticed was that he really knew how to play Latin music,” Pacheco recalled decades later. “When he took a solo, that’s when he really got me. He used to take incredible solos. You could tell he had really listened to [the jazz pianist] Peruchín and all those guys in Cuba. The scales he used to play, I was flabbergasted.”

Harlow became one of the most prolific artists of this quintessential New York label, recording more than 200 albums by various artists and 50 of his own. He was the first to develop the front line of two trumpets and two trombones that most salsa bands use today.

In addition, his 1965 debut album, “Heavy Smokin,’” featured his then girlfriend Vicky Berdy playing congas, something unheard-of in the male-dominated Latin music world. He later produced the all-female orchestra Latin Fever.

When Arsenio Rodriguez, a blind Afro-Cuban musician died in 1970, Harlow recorded a tribute album.

“Without Arsenio there is no salsa,” he said. “This man, who was the first to add the conga drum, the piano, multiple trumpets and more to the music, had died in obscurity. No one in the Latin scene did anything in tribute to him. As a Jew I would hear the occasional snide comment about me being an outsider. That album helped to erase some of that snide commentary and got me some respect.”

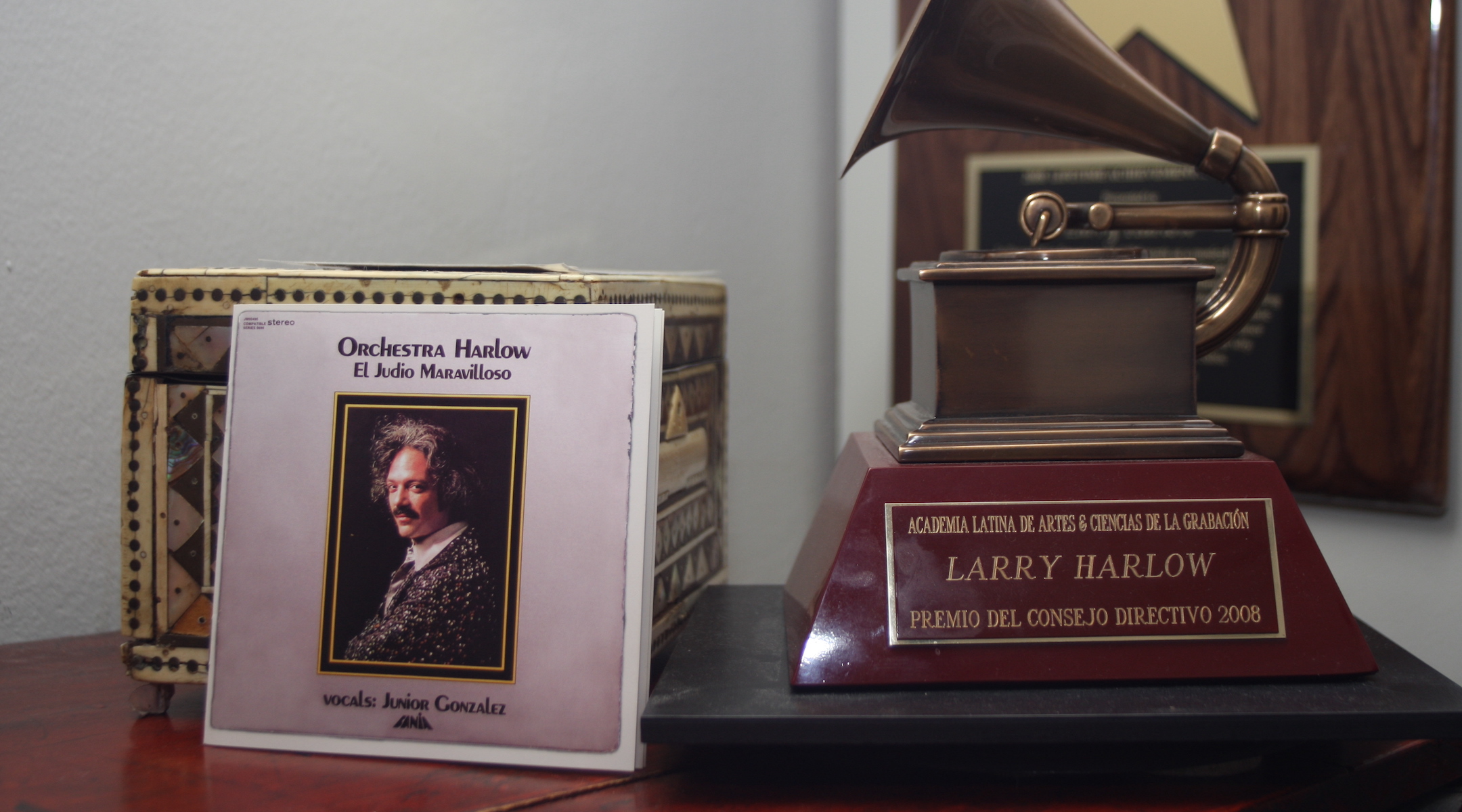

Harlow’s nickname, “El Judio Maravilloso” — “The Marvelous Jew” — is featured on a CD. (Julian Voloj)

Rodriguez was nicknamed “El Ciego Maravilloso,” “The Amazing Blind Man” — and soon Harlow would be called “El Judio Maravilloso.” At concerts, hosts and emcees would shout out in Spanish: “And now the amazing Jew!” No further explanation was needed. Harlow proudly embraced the moniker.

Perhaps Harlow’s most enduring legacy was an initiative he spearheaded in 1974, collecting over 100,000 signatures for the recognition of Latin music by the Grammy Awards. That year he protested in front of the venue where the awards ceremony was being held — and it worked. Three decades later, in 2008, Harlow would receive the Trustees Lifetime Achievement Award from the Recording Academy, which bestows the Grammys.

Many Latinos declared him an honorable Puerto Rican. It was an honor that he gratefully accepted, but he would often declare: “I’m a proud SOB,” or “Son Of Brooklyn.”

“You can take the boy out of Brooklyn, but you can’t take Brooklyn out of the boy,” he also liked to say.

As Harlow proudly showed me the Santeria shrine in his New York apartment in 2010, he declared, “I never pretended to be someone I wasn’t. I was always proud to be Jewish.”

Visiting Cuba exposed him to music’s African roots, and as part of his immersion into the culture, he became a Santeria priest in 1975.

“There is no conflict in me being Jewish and a santero,” he explained. “Whether it’s Kabbalah or Santeria, it’s as a form of protection.”

We had met shortly after his performance of “La Raza Latina: A Salsa Suite” at Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park, which broke the park’s attendance record. Originally composed in 1976, the concept album traces salsa’s roots from West Africa to Cuba and finally to New York City, underlining the multilayered identity of the music. Like the city in which the style was created, salsa is a melting pot of genres such as mambo, son montuno, Latin jazz and other elements.

As Aurora Flores, who had worked with Harlow on his memoirs, put it: “A new music was born on the streets of New York, and Larry Harlow was one of its fathers. […] It was a sound conceived by the American-born children of Puerto Rican citizens, Cuban and Dominican immigrants, African-Americans and the great-grandson of an Austrian rabbi.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.