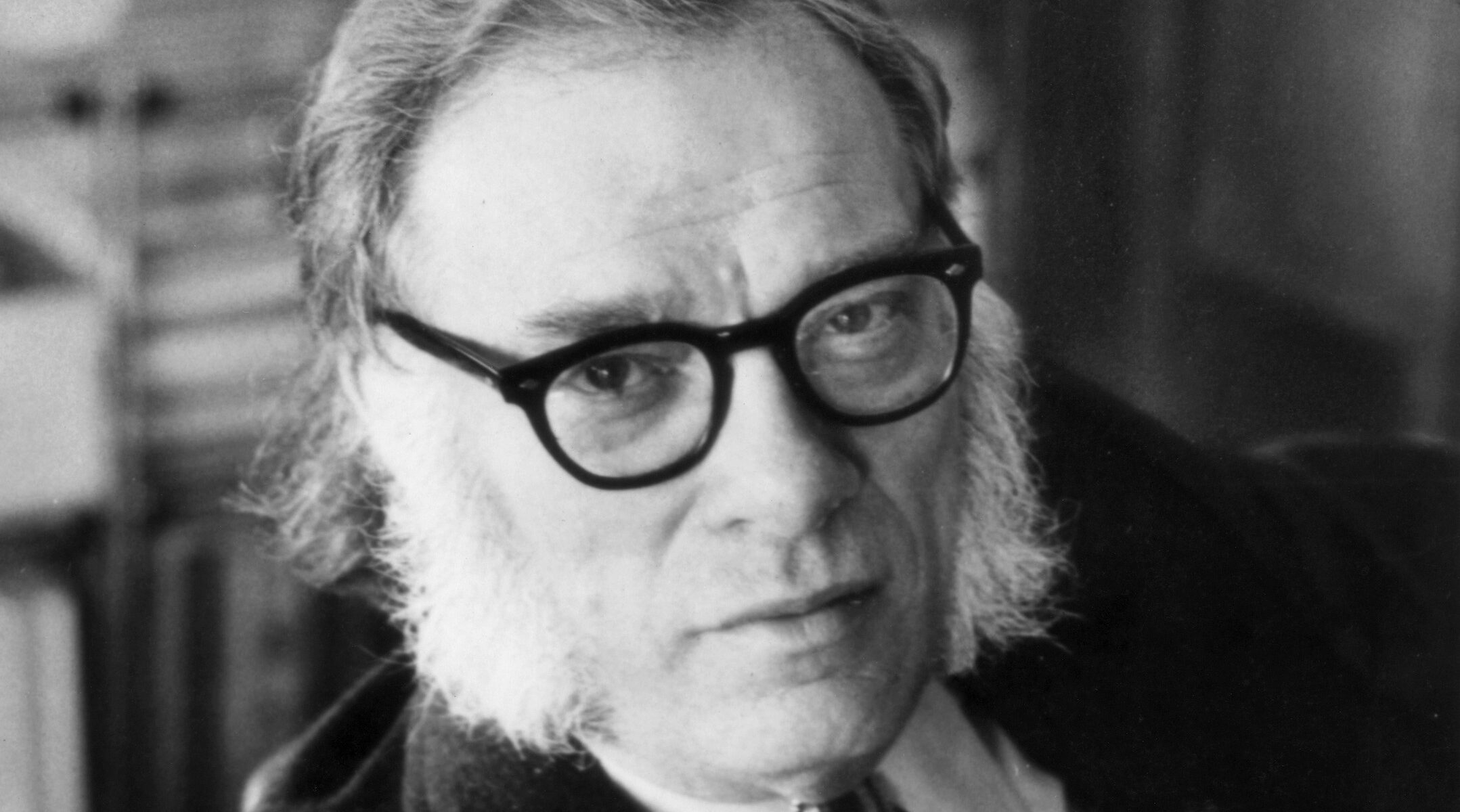

(JTA) — This Friday, following a pandemic delay, Apple TV+ will debut “Foundation,” the first-ever screen adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s bestselling, award-winning science-fiction book series. First announced in 2018 and produced in association with Skydance Television, the TV show is one of the Apple streaming service’s most expensive and ambitious productions to date.

The series, which follows a mathematician struggling to convince a galactic federation that their society is on the brink of collapse, blends anxieties of the 1940s and ’50s, when the source material was originally written, with modern global concerns like climate change.

It was co-created by Josh Friedman and David S. Goyer. Friedman identifies as Jewish, while showrunner Goyer, son of a Jewish mother, wrote and directed the dybbuk-themed 2009 horror movie “The Unborn.”

But what of Asimov himself, a biochemist at Boston University and one of the most influential sci-fi writers of all time? That’s a much more complicated question.

Isaac Asimov was born in Russia in 1920, and his family emigrated to the United States when was 3 years old. He had Jewish parents who were themselves raised Orthodox, and they raised him in Brooklyn. However, Asimov gravitated to more humanist beliefs from an early age, and as an adult identified vocally with atheism until his death in 1992.

So on the one hand, Asimov became one of pop culture’s most prominent atheists; and on the other, he was open and prideful about his Jewish heritage.

Lou Llobell in “Foundation.” (Apple TV+)

The author addressed his beliefs and background in his posthumous 1994 memoir, “I, Asimov,” stating that his father, “for all his education as an Orthodox Jew, was not Orthodox in his heart.” While acknowledging that he and his father had never discussed such matters, he speculated that his father, having been “brought up under the Tsarist tyranny, under which Jews were frequently brutalized,” had “turned revolutionary in his heart.”

Asimov did not have a bar mitzvah, which he attributed to his parents choosing to raise him without religion and not, as some suspected, “an act of rebellion against Orthodox parents.” However, he said, he “gained an interest” in the Bible as he got older, although he eventually realized that he preferred the type of fictional books that would one day make him famous: “Science fiction and science books had taught me their version of the universe and I was not ready to accept the Creation tale of Genesis or the various miracles described throughout the book.”

Having the first name “Isaac,” in the 21st century, isn’t necessarily a certain giveaway that a person is Jewish. But in Asimov’s time, it almost always was. And while Asimov sometimes faced pressure to change his name for professional reasons, he always stuck with his given name.

“I would not allow any story of mine to appear except under the name of Isaac Asimov,” he wrote. “I think I helped break down the convention of imposing salt-free, low-fat names on writers. In particular, I made it a little more possible for writers to be openly Jewish in the world of popular fiction.”

Asimov is one of the most prolific authors in history, having written or co-written more than 500 books in his lifetime. And he did explore Jewish liturgy in such books as “Words in Genesis” (1962) and “Words from the Exodus” (1963). The bulk of his literary work, however, did not touch on Judaism.

His memoir also takes issue with an academic critic who, in 1989, accused Asimov of using “more themes in his work that derive from Christianity than Judaism.”

“This is unfair,” Asimov wrote. “I have explained that I have not been brought up in the Jewish tradition. I know very little about the minutiae of Judaism… I am a free American and it is not required that because my grandparents were Orthodox I must write on Jewish themes.” He went on to write that Isaac Bashevis Singer “writes on Jewish themes because he wants to [while] I don’t write on them because I don’t want to.”

“I am tired of being told, periodically, by Jews, that I am not Jewish enough,” he wrote.

Asimov also devoted a chapter in the memoir to antisemitism. He noted that his family never suffered from pogroms or other overt antisemitic terror either back in Russia or in the U.S., nor did antisemitism never impeded his own personal success. But he did find it “difficult to endure… the feeling of insecurity, and even terror, because of what was happening the world,” especially at the time of the Holocaust. He also told the story of a public argument he once had with Elie Wiesel, in which Wiesel said he did not trust scientists and engineers, because of their role in the Holocaust.

As for Israel and Zionism, Asimov was something of a skeptic. In his final book “Asimov Laughs Again,” published around the time of his death, Asimov stated that he had never visited Israel and didn’t plan to, although he attributed that in part to his habit of not doing much traveling.

“I remember how it was in 1948 when Israel was being established and all my Jewish friends were ecstatic, I was not,” he wrote. “I said: what are we doing? We are establishing ourselves in a ghetto, in a small corner of a vast Muslim sea. The Muslims will never forget nor forgive, and Israel, as long as it exists, will be embattled. I was laughed at, but I was right.”

Isaac Asimov died in New York City in April of 1992, at age 72. His family revealed years later that he had contracted HIV from a blood transfusion following heart surgery nearly a decade prior, which led in part to his death.

Asimov did not have a Jewish funeral, or any funeral at all — he was cremated. But at a subsequent memorial service, fellow author Kurt Vonnegut stated that “Isaac is up in Heaven now,” later joking that “that was the funniest thing I could have said to an audience of humanists.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.