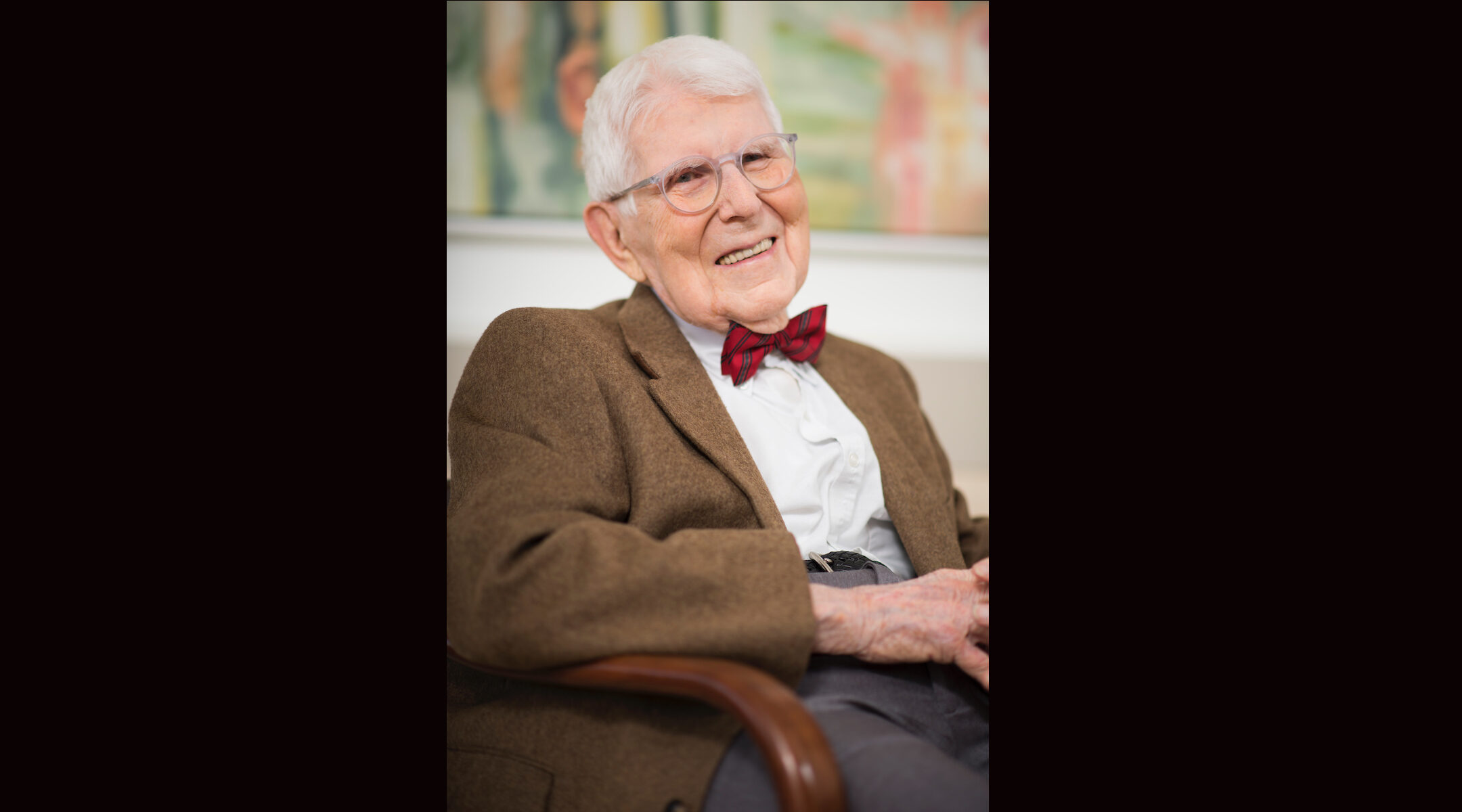

(Philadelphia Jewish Exponent via JTA) — Dr. Aaron T. Beck, who revolutionized psychiatry by developing the field of cognitive behavioral therapy, died on Nov. 1 at his home in Philadelphia.

Born on July 18, 1921, he turned 100 earlier this year.

Beck is known for having developed a transformative psychiatric focus on the day-to-day behaviors in patients. This cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) ran counter to the Freudian emphasis on buried childhood traumas that had defined the field for the preceding century. But it produced tangible results in improving patients’ moods, and today CBT is the world’s most extensively studied form of psychotherapy.

Later in life, Beck also delivered revolutionary research on schizophrenic patients, who had long been written off by the psychiatric establishment.

“My major discovery was that the patients were not really reporting what was important to them — the way they interpreted or misinterpreted situations. People would be trained to make the corrections,” he told the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent in 2017. “Some of the behaviors they recognized, and were able to correct, included depression, anxiety, suicide and obsessive-compulsive disorder. But, until recently, neither I nor my students had done research on schizophrenia, which supposedly would not respond to psychotherapy.”

The Beck Depression Inventory, a 21-question self-inventory, was developed in 1961 and remains a leading test for measuring the severity of depression.

The medical website Medscape noted that Beck had authored more than 600 scholarly articles and 25 books, ranking him as the fourth-most influential medical practitioner within the past century.

“The father of cognitive therapy, Dr. Aaron Temkin Beck is considered one of history’s most influential psychotherapists and a pioneer in the field of mental health,” the publication wrote. “Dr. Beck’s early work on psychoanalytic theories of depression led to his development of cognitive therapy, a new theoretical and clinical orientation, ‘based on the theory that maladaptive thoughts are the causes of psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression, which in turn cause or exacerbate physical symptoms.’”

A native of Providence, Rhode Island, Beck was the child of Russian Jewish immigrants. He settled in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, in the mid-1950s to work at Valley Forge Army Hospital. He spent much of his career at the University of Pennsylvania, concluding as an emeritus professor in the Department of Psychiatry of the Perelman School of Medicine and as director of the Aaron T. Beck Psychopathology Research Center.

Beck is also credited with founding the Beck Initiative in collaboration with City of Philadelphia agencies. The initiative is a partnership between university researchers and clinicians and the city’s behavioral health managed care system that works to ensure that consumers have access to effective mental health care.

At Beck’s funeral on Nov. 3 at Temple Beth Hillel-Beth El in Wynnewood, where he was a lifetime member, his children eulogized their patriarch, known to loved ones as Tim.

Oldest son Roy Beck said he talked to his father often, including every day from April 2020 to his death.

Roy Beck said his father was working on a paper at the time of his death, despite being bedridden and too weak to move for himself.

“Most days, when I asked how his day went, he said, ‘I had a good day,’” Roy Beck recalled.

“I’ve never retired because I love what I’m doing,” Dr. Beck said in the 2017 Exponent article. “All the time I’m on to new discoveries and applications. So there hasn’t been any phase in my professional career where I wasn’t working on something new.”

His daughter, Judge Alice Beck Dubow of the Pennsylvania Superior Court, said she went over to her father’s house for lunch several years ago and began discussing one of Dr. Beck’s patients at Norristown State Hospital. The patient, who suffered from schizophrenia, had assaulted an aide and gotten incarcerated.

Dr. Beck argued to his youngest child that every day the patient spent behind bars would erode the progress they had made. His daughter said a crime had been committed.

The psychiatrist saw his daughter’s point, but he was still upset. Years later, Beck Dubow realized that her father was right.

“There should have been extra care,” she said, adding, “He nurtured my intellectual development.”

His other daughter, Dr. Judy Beck, followed her father into the cognitive behavioral therapy field, founding the Beck Institute in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, with him in 1994.

Later in his life, she noticed that he took a particular interest in an illness he had overlooked: schizophrenia.

Aaron Beck recognized that his usual therapeutic approach — focusing on a patient’s negative habits and views — didn’t work with schizophrenic patients. Instead, he had to motivate them to focus on times when they were at their best.

Those afflicted with schizophrenia suffer from a feeling of disconnection. It was vital to make them feel like they could use their strengths to connect, Judy Beck said.

Her father even told her that maybe he had made a mistake with cognitive behavioral therapy, his life’s work. Maybe he should have been focusing on people’s strengths all along.

“It demonstrated his flexibility,” she said.

Son Dan Beck was not planning on speaking at his father’s funeral. He didn’t think he could sum up a 65-year relationship in a few minutes. But the morning of the service, he took a walk around Wynnewood and it came to him.

Dan Beck recalled that, given his father’s status, his young friends pictured his house as some lively intellectual salon. But when they came over, they didn’t find Freud himself arguing with Aaron Beck in the living room, he said.

Instead, the Becks were just a normal Philadelphia family. They even went to Wildwood every August to go on the boardwalk rides.

Dan Beck’s earliest memory with his father was of him singing, “Danny Boy,” throwing him in the air and catching him. The son cracked up every time. Now, he does the same thing with his kids.

During a difficult period in his 30s, Dan Beck often asked his father for advice. “He said, ‘Just write down three things you want to do today, and as you do them, cross them off,’” Dan recalled. “‘Don’t worry about tomorrow. Tomorrow will work out.’”

“He was right,” Dan Beck said. “Tomorrow did work out.”

Aaron Beck is survived by his wife, Phyllis; children Roy, Judith, Daniel and Alice; 10 grandchildren; and 10 great-grandchildren.

An earlier version of this article was published in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent and is republished with permission.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.