(JTA) — Rabbi Simcha Krauss, a leading figure of Modern Orthodox Judaism who was a forceful advocate for women’s rights within Orthodoxy, died Thursday at 85.

Krauss’s efforts, which included creating a rabbinical court to support women whose husbands refused to divorce them, frequently earned him scorn from traditionalists within Orthodoxy. But many others saw him as a “gentle giant” who wielded his years of study and experience to fight for women’s rights in Jewish law.

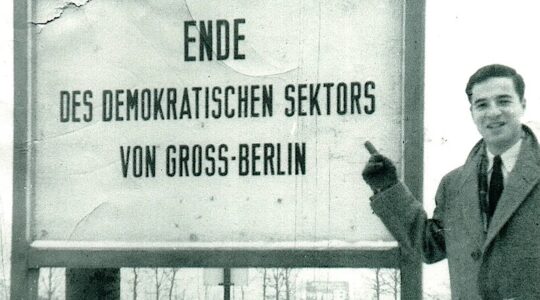

Krauss was born in Romania and came to the United States in 1948. He attended City College in New York and earned a master’s degree from the New School and later taught political science at St. Louis University and Utica College of Syracuse University.

Coming from a long line of rabbis, Krauss studied at Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin in Brooklyn, where he received his rabbinical ordination from Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner in 1963, and later studied with the Modern Orthodox luminary Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik. Krauss served as a congregational rabbi for decades, first in Utica, New York, and later in St. Louis and in the Hillcrest neighborhood of Queens, where he led the Young Israel of Hillcrest for 25 years.

Never miss a story. Sign up for JTA's Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREDuring his years in Queens, Krauss taught Talmud at Yeshiva University and began to get more involved in issues related to the role of women in Orthodoxy. In the 1990s, he began supporting the practice of women’s prayer groups, in which women gathered to worship together without men and often to read from the Torah together, a ritual traditionally only performed by men in Orthodox communities.

When the Va’ad of Queens, a local rabbinical council, met to discuss the issue ahead of a bat mitzvah in the community in which the girl was set to read from the Torah, Krauss defended the practice.

”Some people want something. We are rabbis. We are guardians of the law. Other people want something, and it’s a quest for spirituality, a yearning to be closer to God, and if we can say yes, we should say yes,” Krauss said, according to an article from the time in the New York Times. The Va’ad voted to denounce the practice, but the bat mitzvah went ahead as planned.

In 1996, Krauss’s wife, Esther, became the founding principal of Maayanot Yeshiva High School for Girls, one of the first Modern Orthodox high schools to teach Talmud to women. Esther Krauss survives him, along with their three children and 12 grandchildren.

In 2005, the couple moved to Israel, where Simcha Krauss began teaching at Yeshivat Eretz HaTzvi.

Rabbi David Ebner, one of the heads of the yeshiva who first met Krauss when both were students in Soloveitchik’s class at Yeshiva University, remembered Krauss as brilliant but approachable and funny but never sarcastic. He remembered him sitting in the study hall of Yeshivat Eretz Hatvi day in and day out where, well into his 80s, Krauss regularly learned one-on-one with the 18-year-old boys who came to study there. He was a “gentle soul and a gentleman,” Ebner said.

In his later years, Krauss took what many in the progressive wing of the Modern Orthodox community deemed a courageous step by attempting to solve one of the most challenging Jewish legal problems facing the Orthodox community today: that of agunot, or women whose husbands refuse to grant them a religious divorce, leaving them unable to remarry. Because only the husband can grant a religious divorce, women are essentially powerless in such situations. If they do remarry without a divorce, they are considered adulteresses and the children born of the later marriage would carry the status of bastards.

In 2014, Krauss came back to New York to found the International Beit Din to work on agunot cases. (A beit din is a rabbinical court.) In a 2017 interview with the Jerusalem Post, he told the story of one case where the beit din invalidated the marriage of a woman who had been waiting for a divorce for seven years after concluding based on a video of the wedding that the marriage had not been properly witnessed by Jewish legal witnesses and was thus invalid.

“The goal of this project is to humanize the beit din,” Krauss told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in 2013. “You can’t solve these situations with sleight of hand. But hopefully we can use the right methodology, so that even these situations get solved.”

While the new beit din was praised by some for its daring, it was also criticized by major figures in the Modern Orthodox community, including Rabbi Herschel Schachter, one of the leading rabbis at Yeshiva University. In 2015, Schachter wrote a public letter dismissing the beit din’s rulings and declaring Krauss unfit to render such Jewish legal rulings.

Despite the criticisms leveled at him and his colleagues and the fissures opened up in the Orthodox community, Krauss was undeterred and continued to advocate for his project.

“Some say it is a modern revolution,” he told the Jerusalem Post. “I say that’s the way you should do it.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.