BERLIN (JTA) — Alwin Meyer knew about the Holocaust when he made his first trip to Auschwitz, the Nazi concentration camp, in 1971. At 21, the young German man had grown up in its shadow.

But he was still shocked by some of what he learned.

“I knew about Auschwitz, but not that there were newborns and children in the camp,” Meyer recently told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “It was almost unbelievable. But it is true.”

Meyer has devoted his life since to uncovering and documenting the stories of children who were imprisoned at Auschwitz, and his book about 27 of them comes out this week in English for the first time. “Never Forget Your Name: The Children of Auschwitz” highlights stories of survival and hope, yet does not flinch from the stark reality: that such qualities were rare in this death camp in Nazi-occupied Poland – especially for children.

Translated from German by Nick Somers, the book weaves together the biographies of 27 people who were children when they arrived in Auschwitz, ranging in ages from 1 day to 15 years. Four were born there.

Pregnant women who arrived at the camp were usually murdered immediately. The few babies who were born in the camp were birthed secretly, with help from other inmates and in filthy conditions. Virtually all born in the camp were killed soon after birth.

The survival of any child represents “a type of resistance to the only fate that Germans had planned for the children — namely, extermination,” Meyer writes in his book. “Very many of the children and juveniles in this book are fully aware that their survival was a matter of pure luck.”

The people Meyer interviewed represent a tiny fraction of the children who spent time imprisoned at Auschwitz. Of about 230,000 children – most of them Jewish – who arrived in Auschwitz from the time it opened in 1940, only a few hundred survived, including 60 newborns. In 1971, just 80 of the child survivors were still alive.

Meyer learned those numbers from Tadeusz Szymanski, the non-Jewish Pole who was imprisoned there and was his guide on that 1971 visit. Like many of his German peers, Meyer — born in 1950 in the former West German city of Cloppenburg — wanted to confront the Nazi crimes of his parents’ generation.

Szymanski, who died in 2002, encouraged Meyer to seek the children out; Szymanski had begun the work himself with people who lived in Oświęcim, the town outside the former camp, “who were not even aware of where they came from originally, of who their parents were,” according to Christoph Heubner, executive vice president of the Berlin-based International Auschwitz Committee.

“Today I am 71, and this has been part of my life since then,” said Meyer, who speaks frequently with German youth about his work.

Get more stories like this. Sign up for JTA’s Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREThe conversations filled a gap that Meyer observed in his own family and others. His father never spoke about his time as a Nazi soldier; the family learned that his uncle was in the SS when a notice about his death on the Russian front appeared in the newspaper.

“In a lot of German families, the people who lived through that time didn’t talk about it, unfortunately,” Meyer said.

For his first conversations with child survivors, Meyer was accompanied by Szymanski.

“Otherwise they would not have let me in their home or apartment,” said Meyer, who recalls feeling ashamed as a German. “He did the talking mostly, and I recorded it.”

Over time, Meyer began meeting with survivors on his own, sometimes crying while speaking with them. The work took place mostly during vacations from his day job directing public relations for Action Reconciliation for Peace, a Protestant German organization that works with Holocaust survivors and other populations. He produced several books and a film based on his encounters with the survivors, and has become close to many of them. Some have visited him and his wife at their Berlin home.

Among them was Heinz Salvatore Kounio, author of the Holocaust memoir “A Liter of Soup and Sixty Grams of Bread,” who lives today in the city of his birth – Thessaloniki, Greece.

Kounio and his family were deported to Auschwitz when he was 15. Because they could speak German, they were made to translate instructions to the transports arriving every evening.

“I survived seven selections” in Auschwitz, Heinz told Meyer, referring to the waves in which Nazis killed the prisoners. “At the last one I was very weak and full of indescribable fear. My firm belief in God helped me to stay alive.”

Dagmar Lieblova (née Fantl) was born in the Czech town of Kutna Hora and died in Prague in 2018. Her family was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp outside Prague in June 1942. From there they were transferred to Auschwitz in December 1943, when Dagmar was about 14. Ultimately, she was liberated by British troops from the Bergen-Belsen camp on April 15, 1945: overjoyed, but “no longer capable of visible emotions,” writes Meyer.

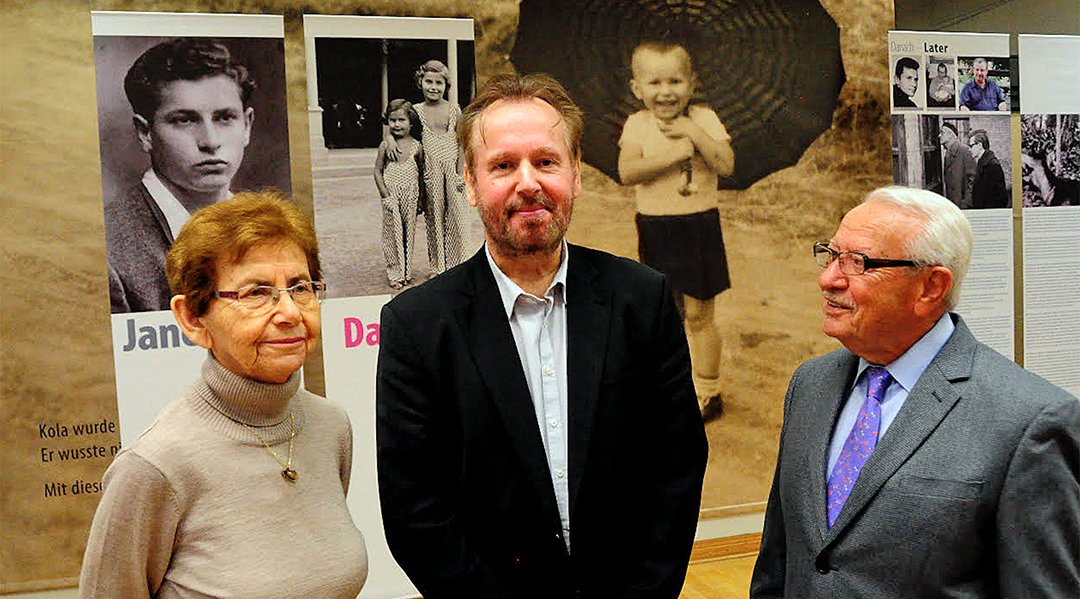

From left: Survivors Dagmar Lieblová and Janek Mandelbaum with Alwin Meyer. (Hubert Kreke)

One of Meyer’s more recent contacts in the book is Angela Orosz-Richt, who was born in Auschwitz. A great-grandmother herself, she lives today in Montreal, where, in addition to working as a caregiver, she volunteers at the city’s Holocaust museum.

“When I talk to people at the museum, I make sure to tell them this is Vera’s story: I am here because of my mother,” Orosz-Richt told JTA.

Her parents, Vera and Avraham Bein, were deported from Hungary, arriving in Auschwitz on May 25, 1944. Vera, who was pregnant, survived medical experiments, giving birth to Angela in December 1944 with help from another inmate, who hid the infant.

Mother and baby were liberated by Soviet troops on Jan. 27, 1945. That day, another child – Gyorgy – was born. Because his mother was unable to produce milk, Orosz-Richt’s mother nursed both babies. Gyorgy lives today in Hungary, Orosz-Richt said.

Orosz-Richt met Meyer in 2018, after years of refusing to speak with non-Jewish Germans. She changed her mind in 2015 after German lawyer Heinrich-Peter Rothmann convinced her to testify against former Auschwitz guard Oskar Gröning, who was on trial in Lüneburg, Germany.

For Meyer, who has spent his whole life wrestling with his family’s and country’s Holocaust history, being able to include people like Orosz-Richt in his book represented a sign of hope.

“The fact that they will talk with me,” he said, “is a leap of faith for the future.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.