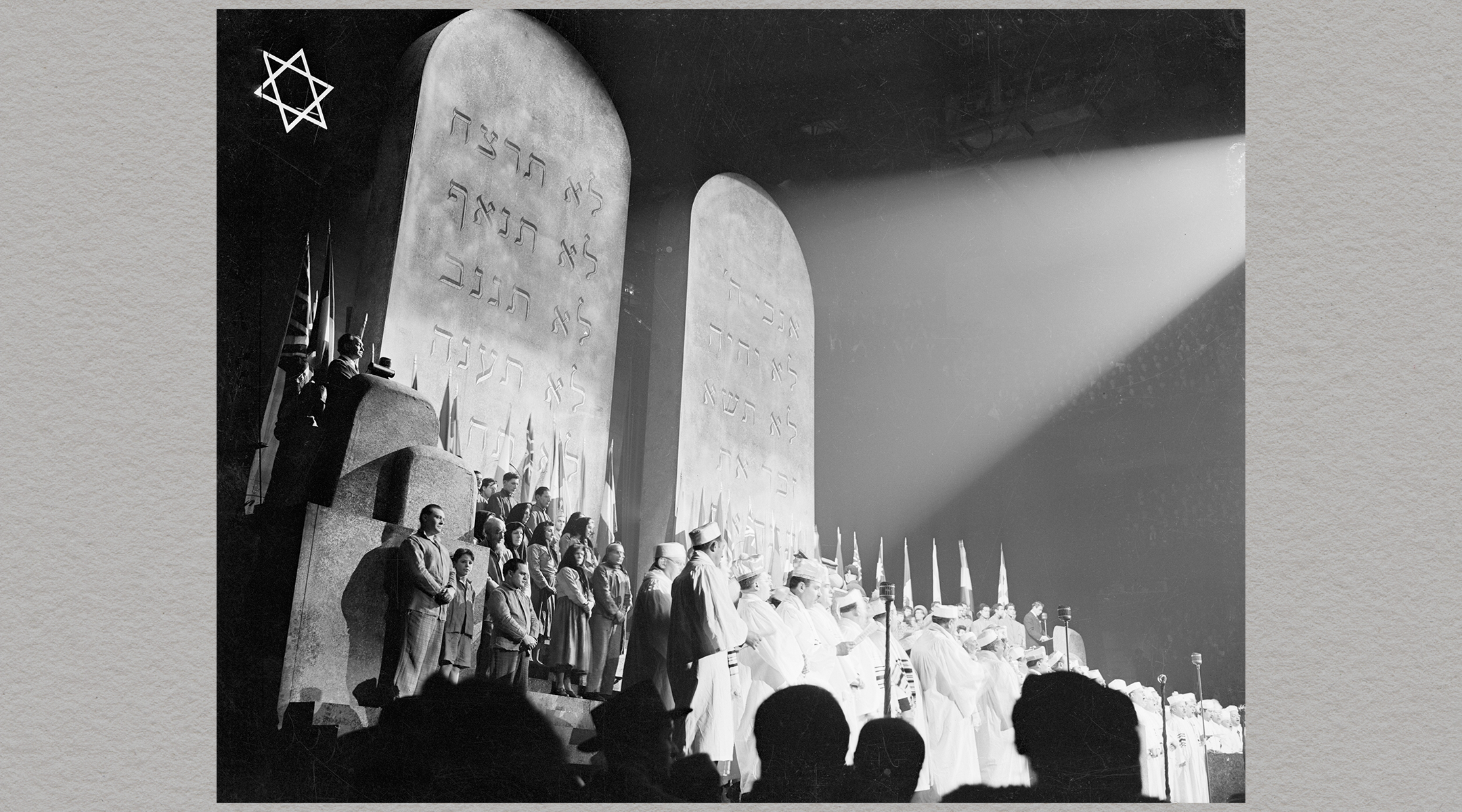

(JTA) — Seventy-nine years ago this month, crowds twice filled Madison Square Garden for a pageant, “We Will Never Die,” meant to draw attention to the slaughter of Europe’s Jews by the Nazis. Screenwriter Ben Hecht organized the spectacle and wrote the script; German refugee composer Kurt Weill wrote the score.

Two million Jews had already been killed. The performance included the lines, “No voice is heard to cry halt to the slaughter, no government speaks to bid the murder of human millions end. But we here tonight have a voice. Let us raise it.”

In the self-congratulatory amnesia called hindsight, American Jews often look back on “We Will Never Die” as a watershed in raising awareness about the Holocaust — and a condemnation of America’s failure at that point to stop the genocide. What’s often forgotten is that Hecht had trouble getting major Jewish organizations to sign on as sponsors. “A meeting of representatives of 32 Jewish groups, hosted by Hecht, dissolved in shouting matches as ideological and personal rivalries left the Jewish organizations unable to cooperate,” according to the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies.

This was 1943, mind you, so the debate over whether the United States should commit blood and treasure to the defense of its Allies was already settled. But the “ideological and personal rivalries” are reminders that Americans were never of one mind about entering World War II, and certainly not about whether and how to save the Jews.

America and its allies are embroiled in a similar debate now, and World War II and its lessons are being invoked by those urging a fierce Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Chief among these are Ukraine’s Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelensky, who has specifically cited the Holocaust in asking governments, and Jewish groups, to intervene.

“Nazism is born in silence. So shout about killings of civilians. Shout about the murders of Ukrainians,” Zelensky said in a call with American Jewish groups. He spoke about the Russian missile strike near the Babyn Yar memorial to slaughtered Jews, saying, “We all died again at Babyn Yar from the missile attack, even though the world pledges ‘Never again.’”

Dmytro Kuleba, the foreign minister of Ukraine, also invoked “never again” in a Washington Post oped. “For decades, world leaders bowed their heads at war memorials across Europe and solemnly proclaimed: ‘Never again.’ The time has come to prove those were not empty words,” he wrote.

The rhetoric may be soaring, but not everyone is convinced. “I’m seeing the term genocide & the phrase ‘never again’ used more in the context of Ukraine,” tweeted Emma Ashford, a senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. “I understand why they’re being used — & the resonance they carry — but they’re not accurate ways to talk about a conventional war between states, even one with humanitarian casualties.”

Damon Linker, a columnist at The Week, made a similar point. “What Russia’s doing is terrible, but it’s what happens in war. It isn’t genocide, and it certainly isn’t the Holocaust, which is what that phrase refers to,” he tweeted. “Please stop the hype.”

In some ways the debate is semantic. ”Never Again” is a phrase popularized by a Jewish militant, adopted by mainstream Jewish groups and eventually absorbed into the global vocabulary as a shorthand for – for what, exactly? Is it about intervention when a government targets a people or ethnic group for slaughter, as in Rwanda? Does it include campaigns of terror meant to “ethnically cleanse” a region, as in Bosnia or Myanmar? Is it about a system of “reeducation camps” meant to erase a people’s culture, as the Chinese are doing to the Uyghurs?

Or, as Kuleba defines it, does it mean “stopping the aggressor before it can cause more death and destruction”? According to that conception of “never again,” the Holocaust may have ended with the death of six million Jews, but it couldn’t have begun without unchecked territorial expansion by a brutal regime.

The debate is also highly concrete. If Kuleba is right, history will judge America poorly if it doesn’t do more to stop Russia’s attacks on civilians and its razing of Ukrainian cities.

And yet, while the United States and its allies have committed arms and sanctions meant to cripple Russia’s economy, President Biden has ruled out sending ground troops to defend Ukraine, or enforcing a “no-fly zone” over the country that would make direct conflict with Russian jets inevitable.

The bloody Russian invasion, bound to get bloodier still, has not risen to what most people and official bodies would call a genocide. And even if it were to, it would be surprising if the United States would commit troops to the battlefield. Most Americans have little stomach for a hot war with Russia. The threat of nuclear escalation is terrifying.

A Cygnal poll taken last week found that 39% of U.S. respondents supported Washington “joining the military response” in Ukraine – a plurality but hardly a landslide. A broad majority still preferred non-military intervention.

The United States, like the rest of the world, has a checkered history in fulfilling the promise of “never again.” Bill Clinton was ashamed of America’s inaction in Rwanda. Barack Obama in 2012 launched a White House task force called the Atrocities Prevention Board, although it didn’t prevent the mass slaughter of Syrians by their own government and Russia on Obama’s watch.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has a Center for the Prevention of Genocide. And yet as Stalin purportedly said about the Vatican, “How big is its army?”

And yet, many refuse to allow realpolitik to deaden their response to the tragedy in Ukraine. “We can discuss and debate a no-fly zone, but there is one thing we can’t debate, and that is this should be a no-cry zone,” said Rabbi Joseph Potasnik, head of the New York Board of Rabbis, during a recent interfaith service for Ukraine. “We should never, ever see innocent people mercilessly murdered.”

Few could dispute that. But if nothing else, history reminds us that slogans are not policies, and that the very best intentions crash up against self-interest and self-preservation. If nothing else, the debate over “never again” demands more humility and forgiveness in judging the failures of previous generations.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.