MONTREAL (JTA) — In her 96 years on earth, Lilly Toth didn’t get much of a formal education. Born in Budapest in 1925, the self-proclaimed spoiled brat often misbehaved and was frequently suspended from school.

But instead of attending university in her late teens, the Holocaust survivor was literally running for her life — hiding with neighbors, surviving an attempted execution on the shores of the Danube, then working for the very fascist organization that attempted to take her life.

Despite these huge upheavals and larger losses, Toth managed to amass something very small, and very valuable: a collection of 1,119 miniature books that are a testament to Toth’s resilience and worldliness.

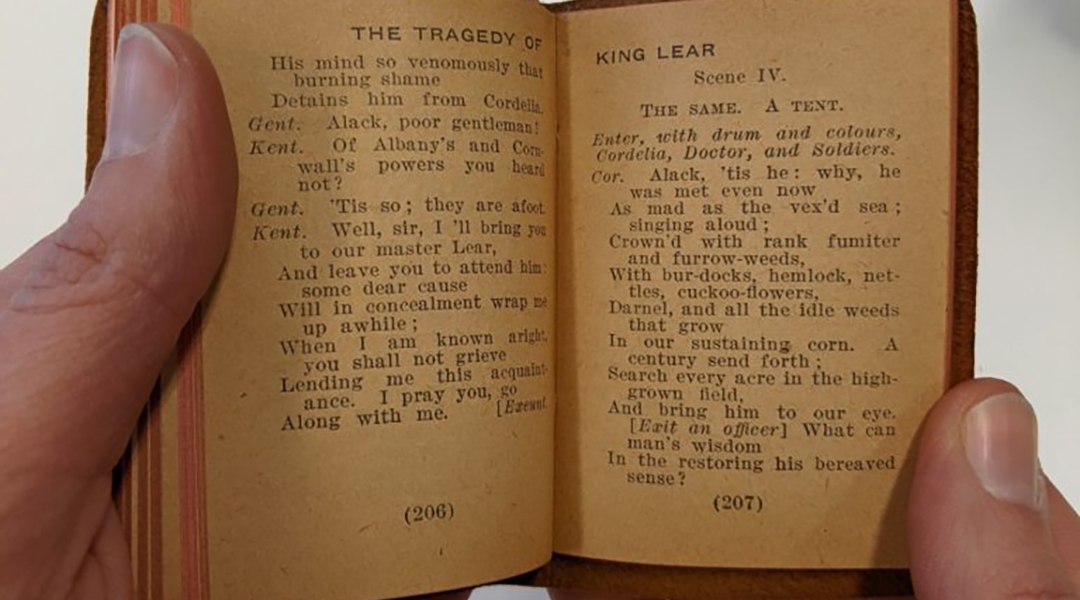

Toth’s collection, which she bequeathed to Montreal’s Jewish Public Library prior to her death last May — and which the library will honor in an exhibit starting May 15 — is as diverse as the inside of a Barnes & Noble. There are cookbooks, musical scores, sports-themed books, novelties known as “mass-market minis” because of their ubiquity, and children’s literature, including “The Tales of Peter Rabbit,” first published between 1902 and 1909. Shakespeare features prominently in two nearly-complete 24-volume sets published between 1890 and 1930.

One book from Toth’s series of miniature Shakespeare volumes. (Toth Collection 15.C.11-17)

“I’ve never seen anything like this before and I’ve been working here for 26 years,” said Eddie Paul, senior director of Library and Learning Services at the Jewish Public Library.

It’s also one of the finest miniature book collections in Canada, and likely of Hungarian miniature books in North America, according to the exhibit’s curator, historian Kristen Howard.

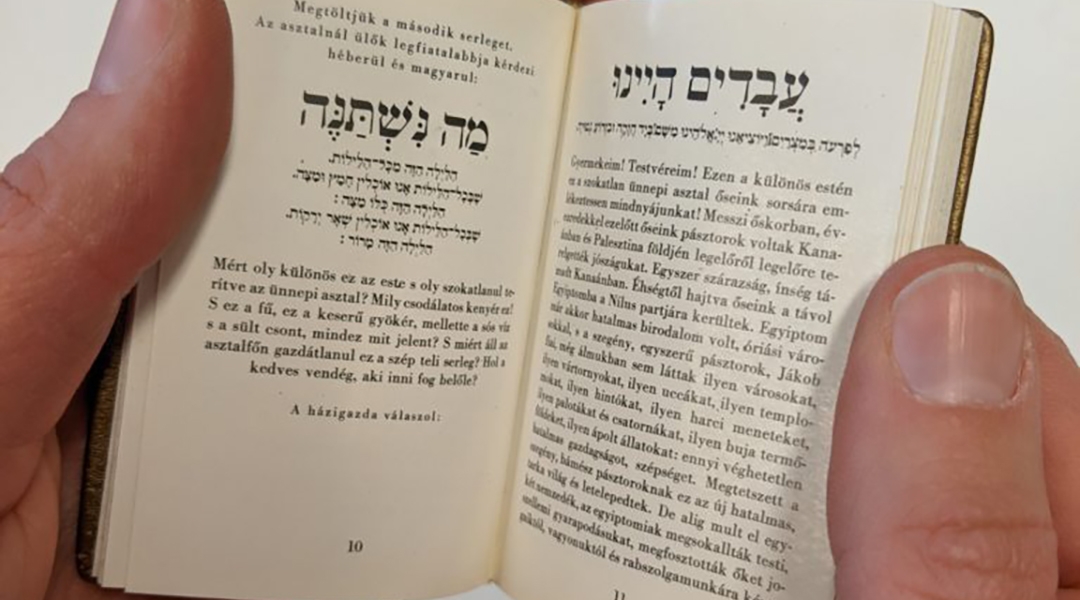

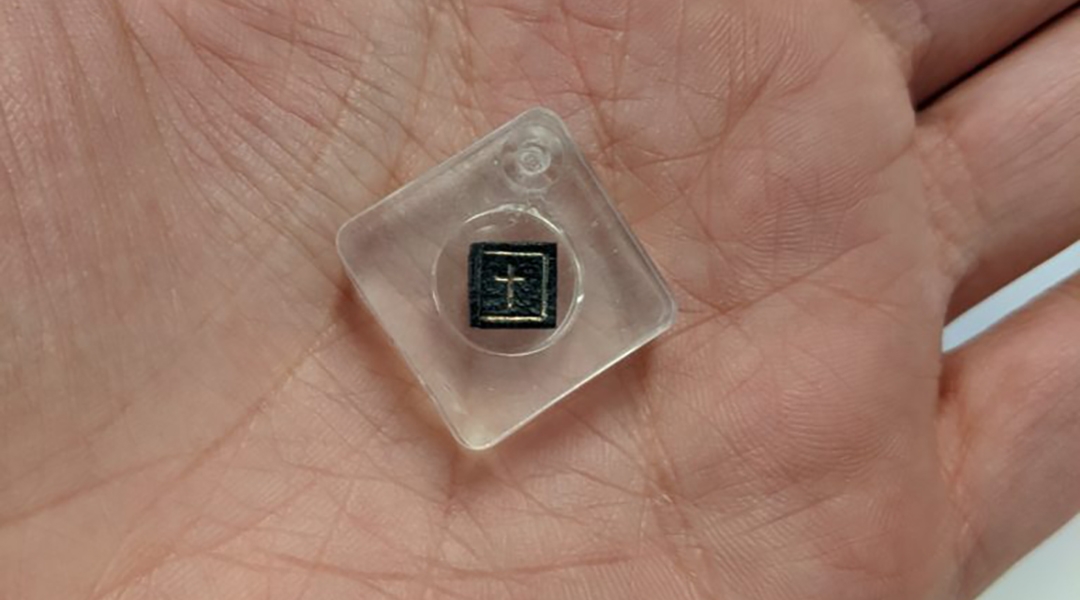

The earliest mini books date back to around 2,000 BCE, Howard noted. In order to qualify as miniature, she says, a book must be bound and smaller than three inches in length and width. Books up to four inches are considered “macrominiatures,” while “microminiatures” are less than one inch, and “ultra-microminiatures” are smaller than a quarter inch. Toth’s collection encompasses all of these, with many so tiny they can only be read with a magnifying glass. For collectors, the allure of minis extends far beyond their cuteness.

“Miniature books are fascinating,” said Howard. “Besides being quaint, practically they’re so easy to transport. So if you have one that is very prized, like a religious book, you can keep it close and safe in a pocket or purse. There’s also something really special about being able to carry all the words of God or works of Shakespeare in your hands.”

This trilingual miniature lists individual and team gold medal winners on behalf of Hungary in the Olympic Games between 1896 and 1972, with pictures of some of the country’s most celebrated athletes. (Toth Collection 10.C.6)

Toth’s collection also includes an early-20th-century English-Yiddish dictionary printed in Germany that packs 1,200 words, sample conversations and vocabulary lists in a palm-sized book. As Howard discovered, the vocabulary lists are curiously all food-related.

“They’re grouped by course,” she said. “Appetizers, mains, desserts, drinks. It’s a nice insight into how it was intended to be used. You could take the dictionary with you to a restaurant and order effectively.”

Raised in a secular home, Toth treasured both Jewish and Christian books, some dating back several centuries. These include Bibles, an ornate Hebrew-Hungarian Passover haggadah and an ultra-microminiature volume of “The Lord’s Prayer” in seven languages. There is an abridged Hebrew-English prayer book, intended for Jews serving in the U.S. armed forces, was first created in 1917 by the National Jewish Welfare Board days after the U.S. declared war on Germany.

While the collection contains English, Hebrew, French, Spanish, German and Russian books, a notable portion comprises Hungarian literature and poetry — a nod to Toth’s roots.

“In the mid-20th century, miniature book collectors considered Hungarian minis to be some of the finest and most prized in the world,” said Howard. “One reason is because they were multilingual, which enabled people from various places to read them, instead of simply admiring them.”

Lilly Toth with her parents. (Courtesy of Toth)

Howard believes Toth was likely drawn to the Hungarian minis because they represented a link to her past and a means of preserving her identity.

“Lilly remained in contact with family and friends in Hungary throughout her time in Canada,” said Howard. “These books were an important touchstone to her culture.”

For Paul, Toth’s rich collection speaks volumes about her family’s scholarship and sophistication.

“Her parents were worldly,” he said. “They were from Austria-Hungary; that was their tradition. Lilly was probably exposed to music, art, various kinds of culture and manifestations of beauty.”

Paul also speculates that the Holocaust inspired her collection.

Never miss a story. Sign up for JTA's Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HERE“The Holocaust motivated people to create and collect beautiful things and preserve them so that others could appreciate them,” said Paul.

While little is known about Toth in later life, she recorded her oral history in 1994 for the Montreal Holocaust Museum and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“We only know Lilly’s story because she shared it with us,” said Eszter Andor, the Montreal museum’s oral history and commemorations coordinator. “Every testimony is precious, and we are so grateful to all of the survivors who have and continue to tell us their stories.”

Toth was born in Budapest, the only child of Viktor and Carla Gluck. After Germany invaded Hungary in 1944, the fascist Arrow Cross movement united with the Nazis and seized the Hungarian government. Viktor Gluck was sent to a forced labor unit and shot in Austria. Her mother, aunt and uncle were arrested by the Arrow Cross and shot near Győr, close to the Austrian border. Toth hid with neighbors until they were betrayed and forced to flee.

“She was taken with another friend to the shores of the Danube where they were tied together,” said Paul. Her friend was shot and killed. “Lilly managed to unfasten her bonds and swam a kilometer down the icy river.”

A Hungarian police officer rescued her, and, upon learning that she was Jewish, turned her over to German soldiers who brought her to a Jewish hospital to recover. Toth survived the mass deportations of Hungarian Jews that began on May 15, 1944; she survived the rest of the war by working under an assumed identity as a cleaning lady at an Arrow Cross building.

During the Hungarian Revolution in 1957, Toth moved to Canada to be close to family in Montreal. Sometime after she began collecting her prized minis, which she displayed on custom-built shelves in her bedroom.

A mini version of “The Lord’s Prayer” published in 1952 by the German group Waldmann & Pfitzner. At less than 5 mm, this volume is the smallest in the Toth Collection and is technically an ultra-microminiature, the classification for books less than 1/4 inch (6 mm) in all dimensions. (Toth Collection 10.A.25)

“The Hungarian Revolution was the second huge break in Lilly’s life,” said Howard. “It makes sense after these very traumatic experiences that one would be drawn to collecting something so easy to transport.”

Said Andor: “If you think about the history of the Jewish people, how many times we’ve had to flee at short notice, it’s interesting that a Holocaust survivor collected books that would be very easy to just put in your pocket and run for it.”

A year before her death, Paul and a colleague visited Toth to view the collection the Jewish Public Library was to inherit.

“Lilly was a remarkable lady,” Paul said. “She was very understated in her assessment of her life and legacy. To her it was as though everybody had collections like this; it wasn’t a big deal. I had the sense that because Lilly never had children, these books were, in a sense, symbolic children for her.”

Andor is moved by Toth’s resolve to rebuild her life after losing her parents and experiencing such trauma.

“Resilience is a common theme in many survivors’ stories,” she said. “They not only survived; they rebuilt their lives. It’s very important that the next generation does not only see the destruction, but the reconstruction.”

On May 15, Montreal’s Jewish Public Library will launch the Lilly Toth Miniature Book Collection together with the Montreal Holocaust Museum and pay tribute to Toth’s life and legacy. There is an online version of the exhibit here.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.