(JTA) — In May, the Bundesliga, Germany’s top soccer league, concluded its season on what has become a familiar note: the Bayern Munich club won its 10th straight league title, an unprecedented feat in any of the top European soccer leagues.

Although the club has become the most successful team in German soccer history, it wasn’t always a juggernaut. The seeds of its domination were planted in the early 20th century by Kurt Landauer, an early Jewish president of the team who survived the Holocaust and returned to helm the team again in the late 1940s.

Last month, Bayern Munich celebrated Landauer’s crowning achievement — the club’s first national championship win in 1932. But recognition of his influence and status among the club’s hallowed figures was a decades-long process.

Born in 1884 in Planegg, a suburb of Munich, Landauer joined the club a year after its founding in 1900, first as a player, becoming the goalkeeper for its second (or backup) team, and later as an executive. He became the club’s president in 1913.

His first term was interrupted by World War I, during which he fought in the German army, receiving the Iron Cross for his services. After the war, Landauer was again elected as president of the club and proceeded to lead the team into a period of historic growth and development.

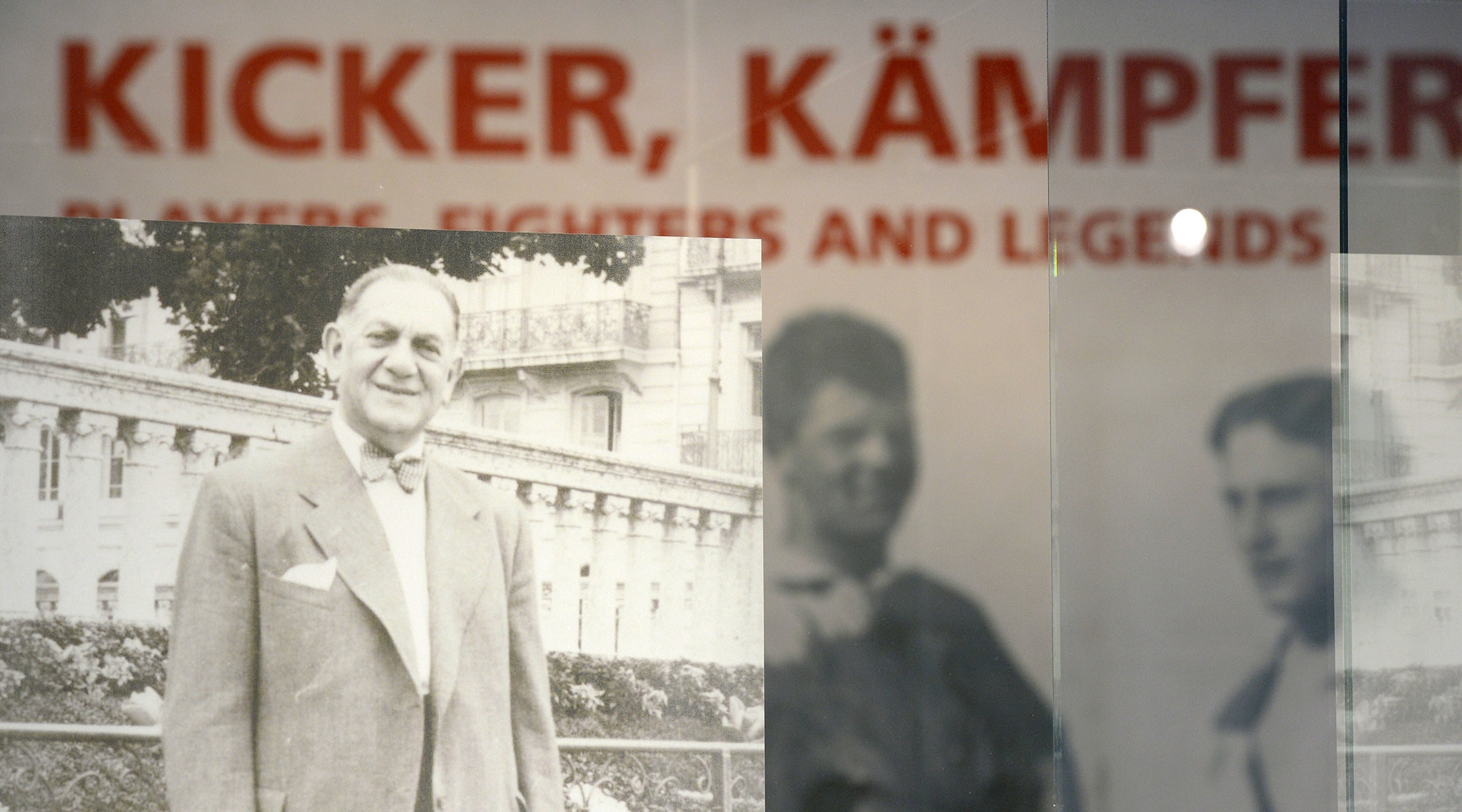

A photo depicting Kurt Landauer is shown at an exhibition titled “Players, Fighters and Legends – Jews in the German football and at the Bayern Munich” at the FC Bayern Erlebniswelt museum in 2015. (Christof Stache/AFP via Getty Images)

Landauer was an advocate of professionalizing soccer (it was considered an amateur pursuit until after World War II) and put an emphasis on the team’s youth academy, which was led in part by Otto Albert Beer, a Jewish FC Bayern official who was later murdered in Auschwitz. Landauer additionally brought in one of the top coaches at the time, the Austrian Richard Dombi (born Kahn) who was also Jewish. Under Landauer’s leadership and Dombi’s coaching, FC Bayern won two South German championships before winning the title on June 12, 1932.

The 1932 champions were widely considered the team of the future, but half a year later, German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as chancellor of Germany. Key figures left the club, among them Coach Dombi, who would continue his career with a number of prominent clubs, including Grasshoppers Zurich, FC Barcelona and Feyenoord Rotterdam. Anticipating that having a Jewish president would harm FC Bayern, Landauer resigned from his position in March 1933.

Want the news in your inbox? Sign up for JTA’s Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREDespite the many hardships, Landauer remained in Munich. In 1938, a day after Kristallnacht, he was interned in the Dachau concentration camp. He was released after 33 days, likely in part because of his World War I service.

The experience destroyed his last hope that things would turn for the better. He fled to Switzerland in May 1939, where he would survive the rest of the Holocaust. Four of his siblings were murdered by the Nazis.

Landauer returned to Munich in June 1947, and less two months later he again became president of FC Bayern Munich. Under his presidency, he recruited new talent and was instrumental in finding a permanent practice area in the city, now called the Säbener Strasse, where FC Bayern has had its club premises ever since.

The club celebrated its 50th anniversary, in 1950, under his presidency. In the aftermath of the war, Landauer’s status as a Jew boosted the club’s reputation, especially with Western fans.

But then, in 1951, he was surprisingly voted out of the presidency. He died in 1961.

For decades, Landauer’s legacy fell into obscurity. In 1993, when working on a book on soccer and racism, the German historian Dietrich Schulze-Marmeling rediscovered his story.

“I was writing a chapter on Jews and antisemitism in soccer. That’s when I realized that it was a buried story. Jewish citizens and their contributions were written out of history from 1933 onwards—and were not written back in after 1945,” Schulze-Marmeling said.

Simon Mueller, chair of the Kurt Landauer Foundation, next to the Landauer sculpture at Bayern Munich’s training grounds. (Julian Voloj)

Like many other Germans, Simon Mueller, a member of the Bayern fan club Schickeria, learned about Landauer from Schulze-Marmeling’s book.

“For a long time, the memory of club’s own history and especially that of the Holocaust did not play a major role at FC Bayern,” Mueller said. “This was not handled differently than in other areas of society in Germany, but it was highly problematic because sport was and is neither apolitical nor innocent. It bears social responsibility and is part of society.”

In 2006, the year Germany hosted the soccer world cup, Schickeria launched an annual antiracism fan tournament named in honor of Landauer. Some participants unveiled a large banner with his face on it during a game.

“The tournament played a major role in the fact that the name Kurt Landauer and his story have become central elements in the identification with FC Bayern for many fans,” said Mueller, who is not Jewish. “Dealing with the past and especially the Holocaust is enormously important. And Kurt Landauer’s biography offers an interesting approach because you can learn so much from it.”

The club’s officials soon took notice. When the club opened a museum in 2012, the permanent exhibition included Kurt Landauer prominently. In 2015, the team renamed the plaza in front of the stadium Kurt-Landauer-Platz and erected a memorial plaque of his face. Meanwhile, FC Bayern fans, led by Mueller, created the Kurt Landauer Foundation, an initiative to coordinate and promote projects related to remembrance work and the history of the club. Their first initiative was a fundraising campaign to build a statue of Landauer — money for the nearly $80,000 sculpture was entirely raised by the fans. The statue was erected at the club’s headquarters, overseeing the training grounds, in May 2019.

Asked what Kurt Landauer means for the club, Andreas Wittner, the archivist of the FC Bayern Museum, shared a quote from Landauer himself, published in the first post-war issue of the club’s newsletter on Nov. 1, 1949: “FC Bayern and I belong together and are inseparable from each other.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.