(JTA) — Becca Balint threw her palms up to her cheeks, mimicking her Holocaust survivor father’s horror when he learned the mailman was friendly.

“He was very, very anxious that the postmaster seemed to know a whole lot about my life and other streets that I lived on,” she said, describing her move to Brattleboro, Vermont, about 15 years ago.

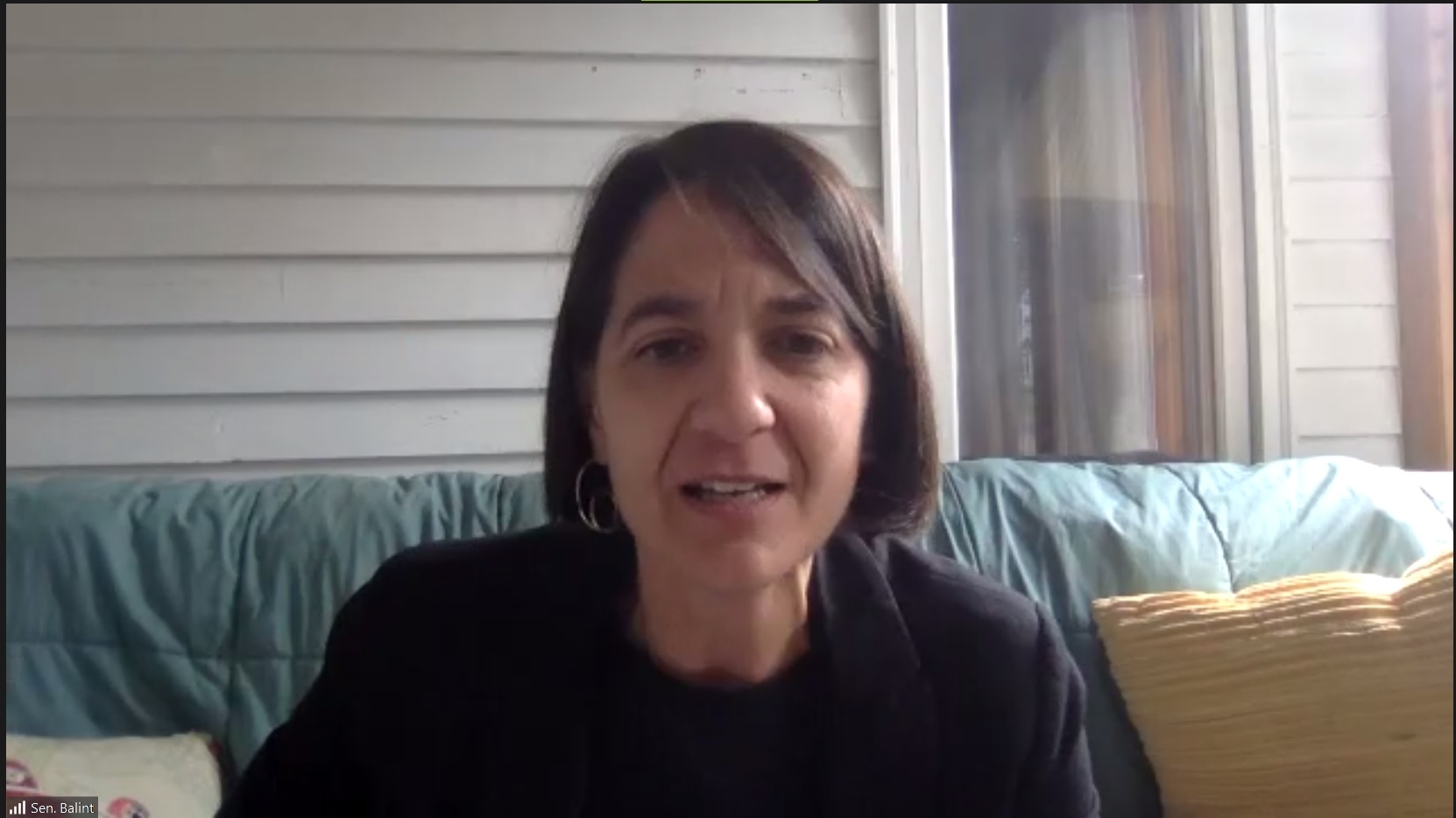

Perched on her porch sofa, Balint leaned into the Zoom camera. “And the letter carrier came by and, you know, he said, ‘Oh my gosh, like, how do you do this? How do you live in a small town where everybody knows your business?’”

Balint, 54, the Democratic nominee for Vermont’s single seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, is running a campaign at once defined by her family’s Holocaust experience and seeking to move beyond it.

If she’s elected (and she likely will be in a district the nonpartisan Cook Political Report has rated safe for Democrats), she will arrive with an ethos defined by the Holocaust to an extent not seen since Tom Lantos, the California Democrat who was the only survivor elected to Congress, died in office in 2008.

“What happened to my family in the Holocaust has guided me my entire adult life, it guided me towards being a compassionate person, to try to, you know, heal divisions,” she said. “This moment of watching the rise of autocrats and authoritarianism, it’s not theoretical for me. It’s impacted my family directly and [it’s important] to make that connection for people, that it’s not something that happened so long ago and it’s still impacting us now, and it can be a guidepost for how we do things in this moment.”

In a strikingly candid interview, Balint explained that her mother isn’t Jewish, and that she is married to Elizabeth Wohl, who also has a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother. Balint describes her family as “Jew-ish.”

“My spiritual life is an amalgamation of Judaism, Quakerism and Buddhism — and I know some of your readers may find this uncomfortable or even offensive,” she wrote in an email on Friday, a day after the interview. “But I think it’s an important part of my story, and I’ve found this not uncommon among left-leaning Jews in Vermont.”

In the interview, Balint recalled conversations with her father as she entered public life, when she was elected to the state Senate in 2014.

“When I was first in elected office, my dad would call me and say some version of ‘Have they slit your tires yet? Have they spray painted your house?’” she said. “And that’s deep trauma, right, so I’m not trying to make light of it, but it was like, ‘Hey, when you greet me with that every time it’s a little challenging.’”

In her email the next day, she wrote, “I want to make sure that I came across as deeply loving and respectful of my dad. He has been through terrible trauma in his life and I know that’s a horrible and painful burden to bear. I would never ever want to come across as disrespectful to him. He has been a wonderful dad.”

Balint shown in a video interview from her porch in Brattleboro, Vt., Sept. 1, 2022. (Screenshot)

She needn’t have worried: It was clear she adores her father. Anyone who knows or who has lived among the second generation of Holocaust survivors immediately understands the push and pull Balint has felt all her life: The survivor parents’ relentless need to protect their children can be a salve and an irritant all at once.

“He brought me up with a strong sense of social justice and a healthy skepticism about the human condition,” Balint wrote of her father. “I use these things every day in my work.”

Peter Balint was born in Hungary, and his family moved to Germany after the upheaval of the war. His family emigrated to the United States when he was 13. Becca Balint was born in a U.S. Army hospital in Heidelberg, where he was stationed. She was raised in New York State and has lived as an adult in Michigan and California before moving to Vermont in 1994.

Balint, who won her Aug. 9 primary resoundingly, has made her father’s Holocaust trauma — but also her determination to emerge from it — a centerpiece of her campaign.

“I know what can happen when we turn away from each other,” is how her signature TV ad begins, featuring photos of her grandfather, Leopold Balint. “My grandfather was murdered on a death march in the Holocaust. I grew up with the knowledge that people can be led astray when they’re scared.”

The segment leads immediately into Balint, her wife, and their two children singing Hanukkah blessings, a public affirmation of Jewish living.

The ad also articulates a worldview directly at odds with her upbringing. “We felt the relief that comes when we stop turning away from each other and start meeting each other face to face,” she says in the ad. “I think that we are often encouraged to shut people out.”

She might as well be describing her father, who she said instilled reluctance to engage with neighbors. “I am a latecomer to the belief that neighbors can be a force for good in the world,” she wrote in 2012, two years before she ran for public office. “My father was always, and remains, hesitant about connecting with neighbors.”

Balint’s neighborliness is what underpins her reputation as a “peacemaker,” earned as a State Senate leader who successfully drove through complex legislation with the backing of all parties.

Balint, who a master’s degree in education from Harvard and a master’s in history from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, described one especially harrowing memory: Her aunt’s teacher in Hungary, gathering information for the authorities, asked students if their parents were Jewish. “These are the wounds that will never, ever heal,” she said.

She said her rival in the primary, Lt. Gov. Molly Gray, appeared in her ads to strike a nativist tone, emphasizing her birth on a Vermont farm. “So many Vermonters during the primary came up to me and said, ‘This isn’t who we want to be,’” Balint said. “Look, I can’t speak to her campaign strategy. But the fact that it didn’t win, I think is very encouraging.” Balint bested Gray 60%-37%.

Her ads also emphasize her firsts, as Vermont’s first woman state Senate majority leader — and, if she wins, its first congresswoman — as well as her legislative wins, in reproductive health, health care and housing.

She was assisted by an endorsement from the state’s Jewish senator, Bernie Sanders. “He said, ‘I don’t want to just give you my endorsement, I want to help you get elected, I want to do this barnstorming tour across Vermont.’ And he said, ‘So first and foremost, we’ve got to feed people. We’ve got to feed people, and we’ve got to give them some entertainment.’ So the band and the food was dealt with first before anything else.” The endorsement rallies this summer featured the band The Western Terrestrials, and mac and cheese.

Balint, ensconced on the party’s left, anticipated pushback from the small cadre among progressive Democrats who back the movement to boycott, divest from and sanction Israel. She emphatically does not support BDS.

“It’s been incredibly painful for a lot of the Jewish community, specifically around Burlington, when the city council was voting on issues related to BDS,” she said. “I’m on the left part of my party. I know that’s going to be a different dynamic. I think it’s counterproductive.”

She has been meeting with the incumbent, Peter Welch, who won the Democratic nomination to replace Sen. Patrick Leahy, who is retiring. She has also been speaking over the phone with Rep. Jamie Raskin, the Jewish Democrat from Maryland. Raskin, a constitutional expert, is on the committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection at the Capitol, led by those repeating Donald Trump’s false claim that he won the 2020 election.

He’s “someone that I shamelessly idolize,” she said of Raskin. “I talked to him just a few days ago on the phone. He said, ‘Becca, we have a democracy to save, that is the work ahead of us.’ And I know that to be true as well. And so I’m going to be looking to people like him who are very clear-eyed on that to help me figure out how to navigate because I’m going to be a sponge.”

According to the family story, Balint’s grandfather, on the death march from the Mauthausen to the Gunskirchen concentration camps in Austria just weeks before liberation, stopped to assist an ailing fellow marcher, knowing that it likely meant they would both be shot — as they were. Balint never explicitly says it, but the choice between annihilation and doing the wrong thing is a no-brainer for her. Balint said she aspired to “subtle fearlessness.”

Asked what that means, she explained, “It doesn’t matter how you push me, it doesn’t matter what you throw at me, bottom line, I know who I am,” she said. “So whatever you throw at me, it’s not going to stick.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.