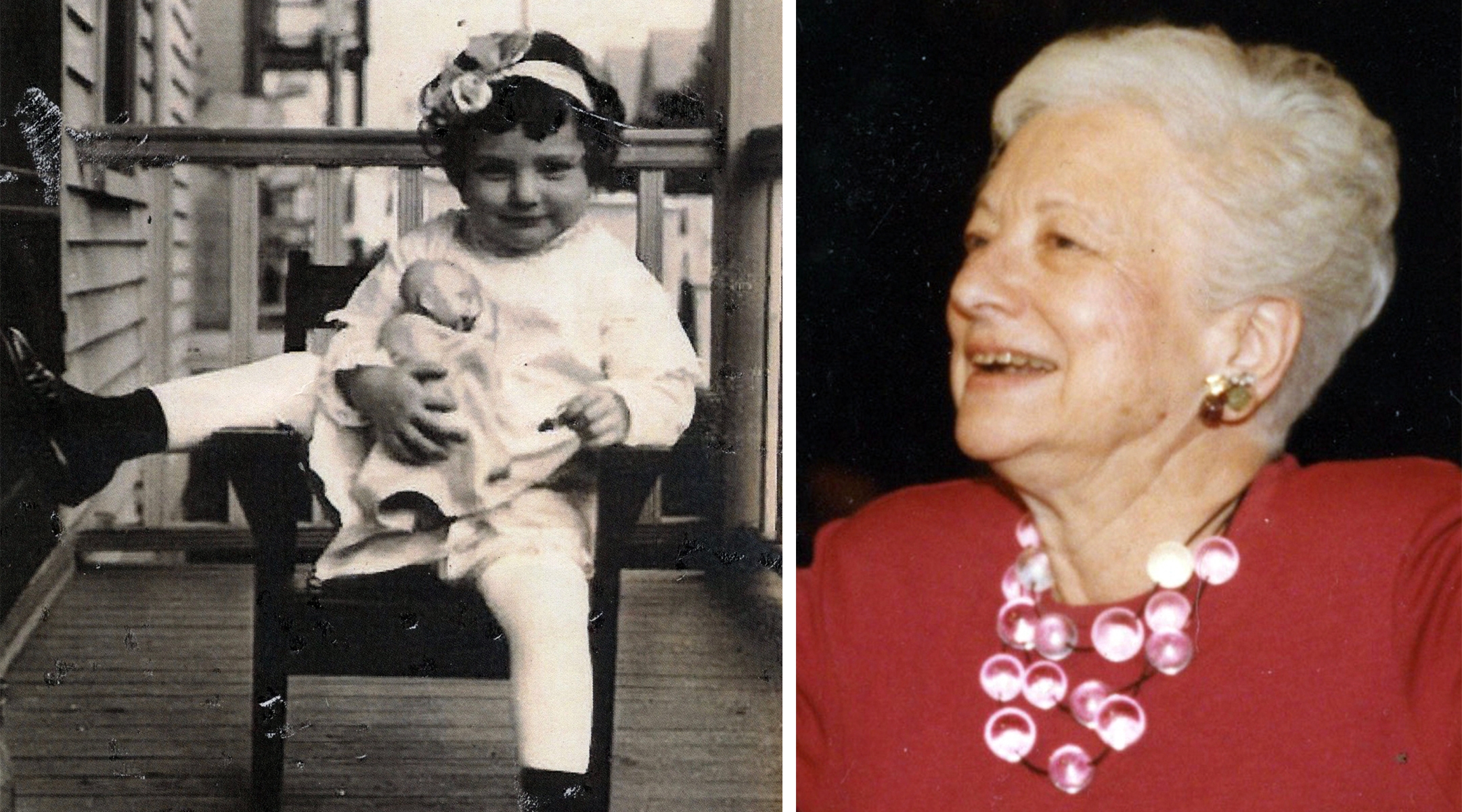

(JTA) — Louise Levy, who was the oldest living resident of New York State and a participant in a genetic study of long-living Ashkenazi Jews, died July 17 in Greenwich, Connecticut. She was 112.

“Throughout her long life, which spanned two global pandemics, she remained a lady in every sense of the word,” her family wrote in an obituary. “She will be unfailingly remembered for her grace, positivity, and kindness.”

Levy, who during her working life served as office manager in a housewares business run by her husband Seymour, was one of hundreds of Jews 95 and older who were recruited in 1998 for a study by the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein School of Medicine in the Bronx. The cohort was chosen because its members, including some Holocaust survivors, are a homogeneous group.

The Longevity Genes Project aims to explore the “good” genes that allow people to live well into the triple digits. “I hope that in our lifetime, we’ll be able to use medicine in order to prevent age-related diseases and improve our quality of life,” its Israeli-born director, Nir Barzilai, said in a statement on the project’s website. “I think it’s our obligation as scientists to do that.”

Its findings so far include mutations in cholesterol genes and a growth hormone gene that are associated with longevity, and evidence that longevity is highly likely to be inherited. Despite their age, many in the study cohort smoked more, exercised less and weighed more than people who had died much younger. (Levy smoked cigarettes until 1965, the year she turned 55.)

Levy, meanwhile, once told an interviewer that her own family history didn’t appear to assure a long life. “My mother was never really a healthy woman,” she told the New York Daily News (although she did live deep into the 20th century). Her father died of cancer and her only brother, Ralph, died of tuberculosis in 1933 at age 34.

Levy often ascribed her longevity to a daily glass of red wine and a low-cholesterol diet, and she said she never eats sweets. “I have orange juice, toast and coffee for breakfast which I’ve had all my life. I eat the same thing for lunch every single day, which is yogurt,” Levy told WCBS 880 in 2019. “I have a feeling that I started eating yogurt when I heard that that’s why the Russians live to such a ripe old age because they eat a lot of the yogurt. So I have that for lunch every single day with a fruit and crackers.

Her family, meanwhile, felt that her “preternatural ability to take life as it came — with the utmost equanimity — must have played a role. Once asked to reflect on the values she prized most, she named honesty, loyalty, and being helpful to others.”

Louise Morris Wilk was born on Nov. 1, 1910. Her parents, Louis Wilk and Mollie Morris, were German Jews who immigrated to Pennsylvania shortly after the American Civil War. Louise grew up in Cleveland, where her father worked as a photographer and movie theater manager. The family moved to Manhattan, where Louis Will illustrated movie posters.

Louise graduated from Wadleigh High School in Harlem before attending Hunter College, although she did not get her degree.

She and Seymour Levy were married on April 28, 1939, and had two children: a son, Ralph, and daughter, Lynn. Both are in their 70s.

In the early 1950s, Louise and Seymour left the Upper West Side and moved to the Westchester County suburb of Larchmont. Louise worked alongside her husband at I. Levy Sons until his death in 1991, and continued to work into her 90s for the man who took over the business.

In what her family calls her “third act,” Levy moved into the Osborn, a senior living community in Rye, New York. There, they write, she “became one of the most popular residents, and a kind of minor celebrity — famed for her indomitable spirit, sense of humor, and, increasingly, her longevity.”

There are 23 verified “supercentenarians” (110 years or older) including one in Japan born the exact same day as Levy.

Levy is survived by her two children, four grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.