(JTA) — Juan Bradman was still in his twenties when he became a circuit judge in rural Cuba, traveling among the provinces.

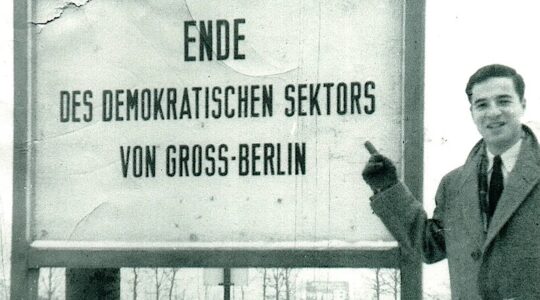

But in 1962, after the communist takeover by Fidel Castro, he and his wife Pola fled Cuba for the United States with their daughter Miriam, who had just celebrated her first birthday.

Years later, Miriam Bradman Abrahams would remember her parents’ story of exodus and exile in the forward to a novel inspired by their lives. “Incident at San Miguel,” written by A.J. Sidransky, was published in May.

“They would leave behind all they knew for another climate, language and culture,” she wrote of her parents. “They could barely imagine the enormity of what faced them. This leaving and arriving, setting down roots and then suddenly having to pull them up to survive, has been part of Jewish DNA for millennia. It is the biblical story of Abraham, Noah, Joseph and Moses.”

Juan Bradman, who lived in Brooklyn, died Sept 23, at the age of 90.

In many ways, Bradman’s was an archetypal story of the more than 90% of Jews who, having found a refuge in Cuba from hardship in Europe, fled once again after Castro’s revolution. After leaving Cuba and putting down roots first in Yonkers, New York and later Brooklyn, Bradman refused to return to Cuba, harboring fears about his safety and his family’s in the country from which he fled. Yet he remained connected to the country by his brother, Salomon, who supported the revolution and chose to remain after the communist takeover.

Despite their political differences and years of estrangement, when the Cuban government opened travel for Cuban citizens to the United States in 2001, Juan sponsored Salomon and his wife for a month’s visit in Brooklyn. (Salomon died in 2012.)

A fictionalized version of their reunion, as well as Juan’s brief encounter with Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, are featured in ”Incident at San Miguel.”

Bradman never lost his bitterness over Castro’s takeover of the country, which replaced the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista with years of deepening repression and economic malaise.

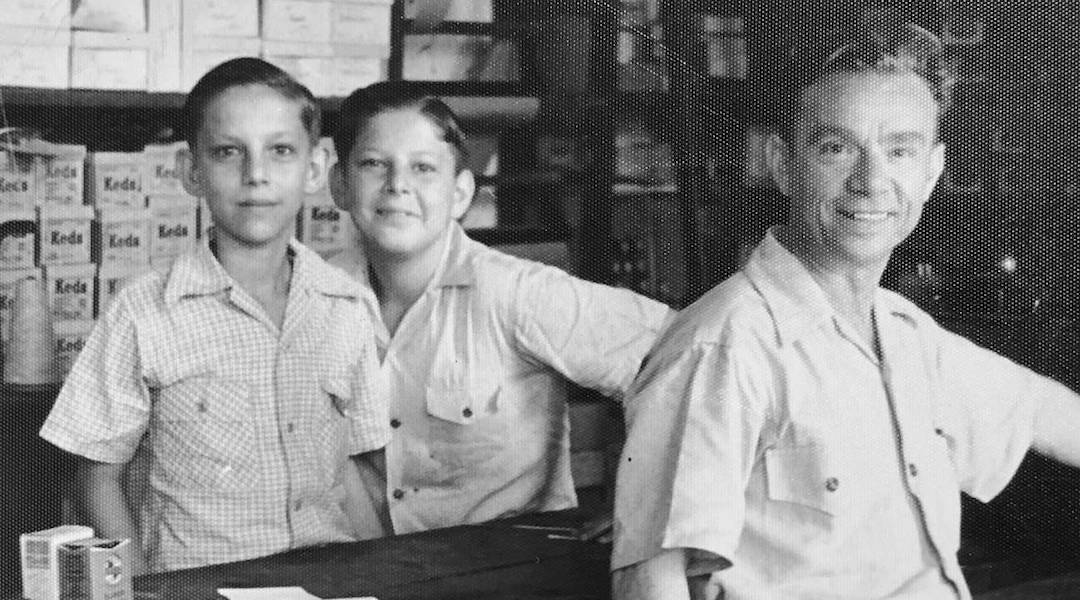

Juan Bradman, shown with his wife Pola, was “beloved by all for his friendliness, sage advice and laughter,” his children recalled. (Courtesy Miriam Bradman Abrahams)

“Fidel was a ruthless Stalinist dictator with a charismatic personality,” Bradman told his daughter after Castro’s death in 2016. “He destroyed the island, running it as his own personal domain. I thank Castro for being the reason we came here. We would not have lived the same quality of life, had we stayed there. History should remember him as a tyrant rather than as a hero or savior. There is an end to everything, and I hope this is the beginning of the end of communism in Cuba.”

Juan Bradman was born on June 24, 1933, the son of Rifka and Yechezkiel Bradman. He and his wife Pola’s parents were refugees from Poland and Belarus. Bradman studied law at the Universidad de Havana before it was closed by the government; he later completed his law degree through the “back door,” according to his family. A stint as a lawyer at the National Bank of Cuba was cut short by political upheaval in Cuba, and in 1959 he was appointed a traveling judge for constituents in the Cuban countryside.

In 1962, he, his wife and daughter fled Cuba “with nothing but six cigars in his pocket, one suitcase of clothes, and a smuggled law degree,” according to a family obituary. “On arriving in Miami, Juan was questioned by immigration authorities to clear up a case of mistaken identity of a cousin with the same name.”

The family continued on to the Yonkers home of an aunt who served as their sponsor, and later settled in Midwood, Brooklyn. Unable to practice law in the United States, he earned a degree from Columbia University, and later a master’s degree in social work. After retiring as a social worker he trained as a docent at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City, where he taught about the Holocaust and shared his immigrant background with visitors.

Bradman was an active member of his synagogue’s Men’s Club and served on the board of his children’s school, Yeshiva Rambam.

Survivors include his wife and his daughters, Sheila Feirstein and Miriam Bradman, two sons in law, five grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

In her forward to the novel based on her parents’ lives, Bradman Abrahams wrote about the ways their parents’ Cuban, American and Jewish identities shaped the lives of their daughters.

“My parents valued education above all else,” she remembered. “Brooklyn’s public schools were not the best back then. Our parents chose to enroll my sister and me in Jewish day school. How I think, speak and react today, what I cook and eat, how I communicate with my parents, my husband, grown kids, and community are a direct result of being tri-lingual and tri-cultural.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.