Remember how candidly Anne Frank described getting her period in her famous diary?

“I can hardly wait,” she wrote. “It’s such a momentous event. Too bad I can’t use sanitary napkins but you can’t get them anymore, and Mama’s tampons can be used only by women who’ve had a baby.”

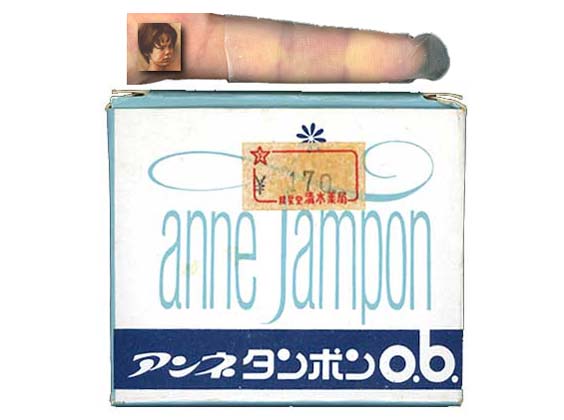

For Japanese readers in the 1960s, Anne’s enthusiasm so compellingly shattered a cultural taboo that not only did the first day of menstruation get the moniker “Anne’s Day,” but a tampon company released a tampon called—yes, exactly as you feared: Anne.

As a recent article in Tablet‘s print edition reminds us, the Japanese fascination with Anne Frank is not all menstrual. And as Alain Lewkowicz, a French Jewish journalist details in his interactive iPad application “Anne Frank in the Land of Manga,” the murdered Dutch girl represents something the Japanese are looking for: historical absolution.

“She symbolizes the ultimate World War II victim,” Lewkowicz told JTA. “And that’s how most Japanese consider their own country because of the atomic bombs — a victim, never a perpetrator.”

The “Anne” tampon was perhaps the earliest example of what Japanese literary scholar Norihiro Kato called the “cuteification” of Anne Frank, and of Japanese history. “It has neutralized issues that are too painful to deal with by rendering them purely aesthetic, and harmless — by making them ‘cute.’”

“Cute” isn’t exactly the word we’d use to describe the tampons, but we do appreciate a good history lesson.

Photos courtesy of Harry Finley.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.