Since Israel was founded, and especially during the Intifada of 2000-2004, Hadassah’s Jerusalem hospitals have been known as bridges of peace, where the staff provides its medical expertise equally to people of every religion, nationality and political persuasion.

Our Arab patient population is especially high at Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus. Part of that population comes from Issawiya, a neighborhood just down the hill from the hospital. Because the neighborhood lies within Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries, residents are entitled to Israeli social benefits, including national health insurance. More than 20 residents, including one surgeon, work at the hospital they often affectionately refer to as "Hadassah Issawiya."

On May 15, the anniversary of Israel’s independence, people coming from Issawiya threw 11 Molotov cocktails and hundreds of rocks at Hadassah Hospital and also set fires at the back gate. The army responded with tear gas and hospital security was even more vigilant than usual in checking incoming patients and visitors for weapons.

But inside, patient care went on as usual. Typical was the pediatric endocrinology clinic, where Dr. David Zangen and Dr. Abdul Salam Abu Libdeh treat young Jewish and Arab patients who have diabetes and growth issues. Palestinian patients and families come in not only from the surrounding neighborhoods, but from all over the West Bank. "I was aware of the extra efforts by security, but the moment I walked into the hospital, my only focus was on my patients," said Dr. Zangen. "I always feel in such situations that we have to be even more determined to remain faithful to our values of equal respect and treatment of all."

The atmosphere of violence at the gate and routine patient care inside is something the staff is accustomed to. There have, in fact, been periodic attacks from Issawiya, including 87 over the past year, though nothing as concentrated as what happened on May 15th.

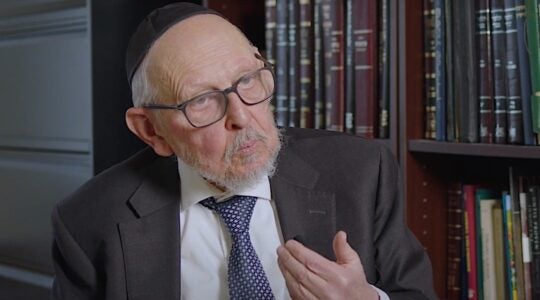

Prof. Zvi Stern, director of Hadassah Mount Scopus, has, in the past, requested that the Imam at the mosque speak against such attacks. At least once during the intifada, such an announcement was made. And more recently, Prof. Stern has asked for representatives of Issawiya to meet with him, but they have declined.

"We can never let the behavior of a group of extremists dictate what we do in our hospital," said Prof. Stern. "They want to destroy the bridges of peace that we are building, and we can’t let them." Prof. Stern sees the increased hostility over the last year and the May 15 attack as signs of growing extremism. "Hadassah Hospital is a symbol of the State of Israel," he observed.

The commitment to equal care, even amid conflict, is as old as the organization itself. Built by Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, the hospital on Mount Scopus opened in 1939. Hadassah’s dedication to ethical medicine was challenged almost from the start. In the months before Israeli statehood in 1948, the two-mile route from downtown Jerusalem to Mount Scopus had become so dangerous that medical personnel and patients traveled to the hospital in vehicle convoys. On April 13, 1948, terrorists ambushed a Hadassah convoy approaching the hospital, killing 78 doctors, nurses, researchers, patients and students. Among the dead was Dr. Haim Yassky, the hospital’s director-general.

By the end of the Israel’s War of Independence, Mount Scopus was cut off, behind enemy lines. Hadassah Hospital moved to a collection of temporary quarters until the women of Hadassah built a new medical center in Ein Kerem. After Jerusalem’s reunification in 1967, Mount Scopus was renovated; it reopened in 1976.

A popular expression says, "No good deed goes unpunished." It’s a true enough statement on human nature that often evokes knowing laughter. But medicine and ethics routinely take us beyond human nature, striving for the ideal. At Hadassah, we believe in doing the deed without regard to the reaction. We treat the patients in our hospitals not according to who they are, or who we might fear they are, but according to who we are.

The writer is president of Hadassah; the Women’s Zionist Organization of America

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.