Ana Levy-Lyons was in her 20s when she found out she was Jewish. During her childhood in Tenafly, New Jersey, her family never spoke about what her mother would later call her “Jewish heritage.” Classic “nones” (what Pew calls the “religiously unaffiliated”), the family observed no religious rituals other than an Americanized Christmas and Easter.

Nevertheless, or maybe inevitably, Levy-Lyons was drawn to matters of the spirit. After a brief career in tech and the music business, she enrolled at the University of Chicago Divinity School, eventually eschewing its dryly academic approach to religion in order to train as a Unitarian Universalist minister. She served for 18 years in “UU” pulpits, including the First Unitarian Universalist Congregational Society in Brooklyn. Now 52 and no longer working as a minister, she is enrolled in the Jewish Renewal movement’s ALEPH Ordination Program to become a rabbi.

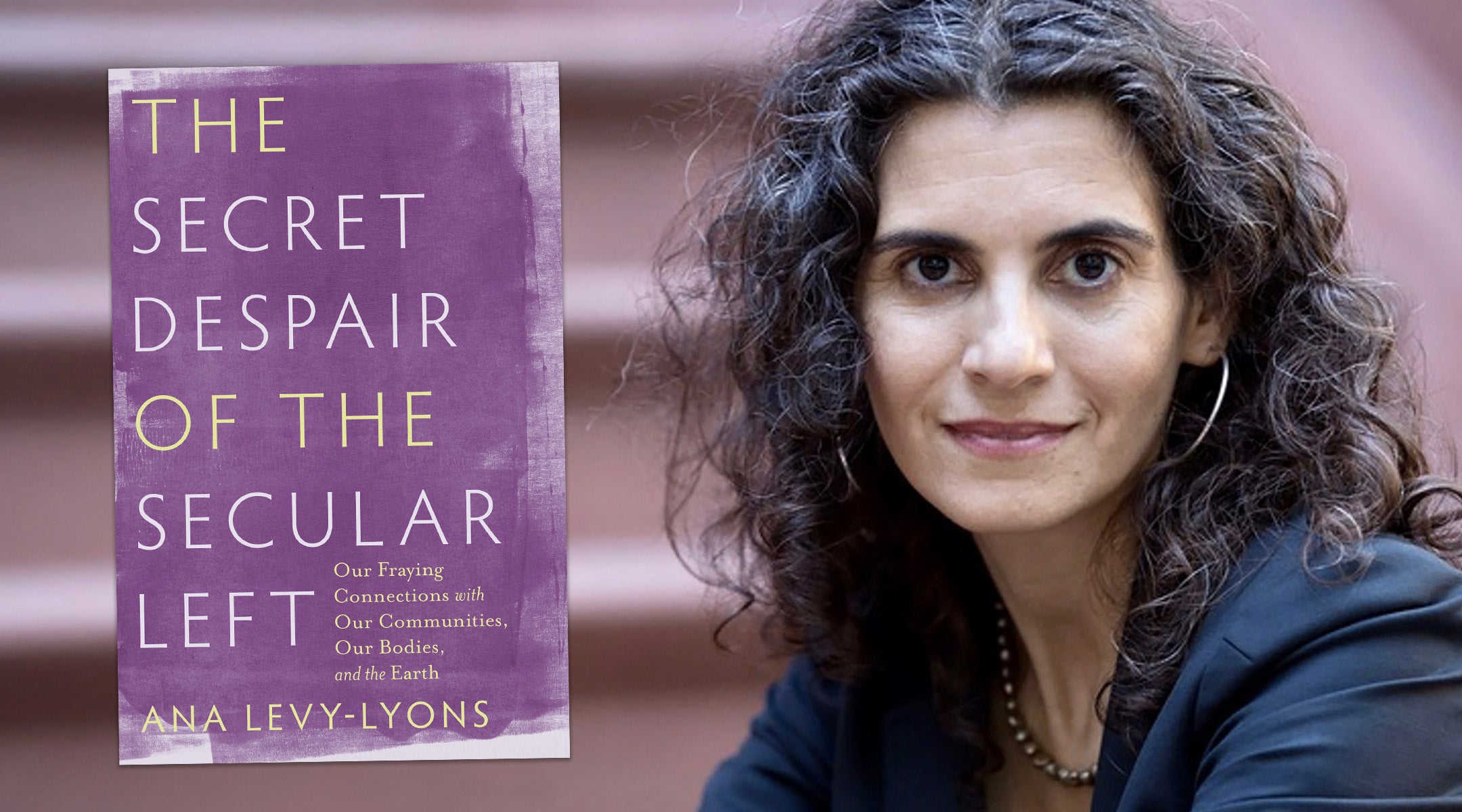

Levy-Lyons might have told a “coming home” story, but her new book takes a different direction. “The Secret Despair of the Secular Left” is less a celebration of Judaism (although there is that) than a searing critique of modern secularism.

As a church without a creed —UU’s pulpits and pews are open to believers and nonbelievers of any stripe — Unitarian Universalism came to represent to Levy-Lyons a “self-assured nothingness” that she sees among “nones” of all backgrounds. Without religious and traditional structures, she asserts, community bonds erode, people become detached from the natural world, and their souls become alienated from their bodies.

“I have come to believe that this is not just my story but the defining story of our time,” she writes. “It’s the story of disembodiment, disconnection, and dislocations. It cuts across class and race.”

She offers religious tradition, especially Jewish traditions, as an antidote to a pervasive sense of grief and longing for deeper connection and meaning. She writes from the left but also against the left, frequently challenging liberal orthodoxies when it comes to feminism, abortion and gender identity.

In an FAQ feature on her Substack, she writes that the book is neither progressive nor conservative — or rather, both progressive and conservative. “I’m hoping that this book can help elevate our discourse beyond today’s political polarization and engage our deeper cultural and spiritual struggles,” she writes. “From my perspective, despite how much the two ‘sides’ hate each other right now, in terms of these struggles we are more similar than different.”

Levy-Lyons, whose previous book was “No Other Gods: The Politics of the Ten Commandments,” recently taught a course on Jewish environmental ethics for My Jewish Learning, JTA’s partner site. She lives on the Upper West Side of Manhattan with her husband and their 14-year-old twins. We spoke Tuesday about what she thinks is ailing the secular left, the alternative that Jewish tradition offers and why at least one reader had trouble squaring her liberal bona fides and some of her heterodox views.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your book is about a break with UU and what you felt able to do and not do as a minister, and by contrast what drew you to reclaim your Judaism. And a big part of that difference is a denomination that doesn’t impart any obligations or “shoulds” on its members, compared to what Judaism knows as mitzvot, which are commandments or obligations. Did I get that right?

Yes, that’s part of it. My first book is about the 10 Commandments, and it’s very much about the liberating power of mitzvot. In the secular-left world, obligations and rules and commandments are seen as oppressive and restricting, and they are in certain ways, but I feel that they actually liberate us from what otherwise is subtly guiding our lives, which is a consumerist culture and the hidden values of secularism, where freedom itself becomes the ultimate good.

You quote your supervisor at a UU congregation in the Midwest: “The most important thing,” he said, referring to your congregants, “is to never make them feel guilty.” Was that the UU ethos?

Yes, freedom and self-determination are much more important than any obligations we might have to somebody else. This is a story I didn’t tell in the book, but I remember when I was in search for what ended up being my Brooklyn pulpit I was interviewing at a congregation, I think it was in Rhode Island. They asked me to put together a workshop or a little class for the search committee. And I asked them to imagine that if they were really, really religious Unitarians, what would that look like? What would they eat and not eat? What would they allow their children to do and not do? How would they dress? How would they spend their time?

They just looked at me like I was from outer space. “There’s nothing that we wouldn’t eat, because we’d be good people, we would eat in ways that are healthy, and do things that are aligned with our values.”

I didn’t get that job.

Let’s talk about the title of your book, “The Secret Despair of the Secular Left.” Define that despair, and what is secret about it.

The despair comes from the kind of mismatch between all of the crises that we’re having in our world today — war and ecological devastation, everything that is happening now — and the despair that comes about when you realize that your spiritual, religious and communal resources are just not up to the task of giving meaning and strength when you need it, nor providing a structure and a sense of connection to the past and the future.

In the beginning of the book, I talk about it in terms of the economic term “unrealized loss.” We invested all of our energy and freedoms into these fruits of modernity and we find that it’s actually kind of worthless. We’ve liberalized ourselves out of any possible sort of meaning or foundation that we could have had.

.“The Secret Despair of the Secular Left” is a searing critique of modern secularism. (Broadleaf Books; Dory Schultz)(Broadleaf Books; Dory Schultz)

Can you give me a concrete example of the kind of investment the secular left has made that hasn’t paid off?

There’s two very easy ones. One is our use of technology and screens. We have this great new technology, and it seems like it allows us to connect meaningfully with people on the other side of the world, and as a result we don’t need to stay rooted in local communities anymore, we can move anywhere we want to for work. So this is freedom, right? You don’t have to remain chained to your local community or your family.

But then we are lonely and depressed in direct proportion to how much we use our phones and use this technology. We’re alienated from one another and don’t have real communities. I think Judaism in particular puts a real value on physical community and roots. There’s the idea of a minyan [the 10-person, traditionally in-person prayer quorum]. There’s a real emphasis on the kind of connectedness that has been broken in the modern world.

The other example is Shabbat. This is an ancient spiritual technology that people are now free from, in the Christian world, too, where blue laws are a thing of the past. Secularism freed us from the oppressive rule of having to not work on one particular day of the week. And as a result of that, we all work all the time, and we’re completely exhausted and overwhelmed. It’s difficult to choose to not work one day of the week when everybody else is working.

And it’s a secret despair because people, especially on the left, don’t want to admit that it’s the very things that they were so proud of, that felt so liberatory, that felt so empowering, that are actually draining meaning from life and causing alienation.

What does Judaism offer as an alternative to this despair?

Judaism offers a multi-generational story of people’s experiences of the divine and how the divine has acted in our lives, with the Torah as the basis for a huge kind of discourse that spans all these generations. It offers us a sense that we are part of something much larger, that we’re not reinventing the wheel. We actually have something to build on, and something not only that we had to build on, but that we are accountable to.

It’s almost like scientific advances — you wouldn’t as a scientist just throw out everything that every scientist has ever done in the past, and then just kind of start again. It doesn’t mean that you can’t revisit some things that you think scientists in the past got wrong. Judaism gives you not only a starting point, but this huge resource that you can draw on: people who for thousands of years have been struggling with things that are in many ways the same things that we’re still struggling with today.

So along with that comes a sense of obligation to the future, and the sense that we’re a part of this tradition, we are making our own contribution to it, and then passing it on to future generations.

To talk about the secret despair of the secular left implies in part that the religious right has gotten it right. I know you don’t believe the religious right has all the answers — at one point you write that you are seeking a middle ground between what you call “a harsh double down traditionalism or a complete abandonment of religious life.” But is there a risk that you are giving too much credit to traditionalism, which comes with a lot of baggage, too, and which many people fled because many religions were oppressive or patriarchal or repressive?

I admit that I might very well be romanticizing the right, because I come from the opposite danger in my childhood, my upbringing and then in my career as a Unitarian minister. Intellectually I know why people have fled the religious right, and all those very real oppressive and patriarchal [tendencies]. But the reason I talk about the secular left in this book, it’s not because I think that the religious right has it correct, but just because the secular left is what I know. I can’t meaningfully critique the religious right from the inside.

I’d like to discuss that critique. You write, focusing on the left, that “today it is almost unthinkable to ask people to give up something for the common good.” But the left is more likely to vote for Democrats, and blue states are much more highly taxed than red states on average, and the left is more likely to demand action on climate change, and urge regulation of corporations and the excesses of late capitalism, and follow pandemic guidelines on masks and closures. Isn’t the left more willing to sacrifice in the sense you write about?

The left and right maybe are willing to sacrifice in different ways. I don’t think that there’s any meaningful difference in how people on the left and the right live in terms of climate change and ecological impacts. I mean, realistically, someone on the left is going to be just as angry if you tell them to give up their hamburger, or not fly in an airplane. They’re not going to do that. I think that people on the right are much more neighbor- and community-oriented. They give more to charity than people on the left, too. So people on the left will vote for higher taxes. But people on the right would say, “Well, I’m going to take that money and give it to charity.”

The left definitely wants the government to, like, make the bad guys stop doing what they’re doing, but I think that people on the left are less willing to look at how we are participating in that same system, and we’re actually perpetuating that same system by buying the things we’re buying or doing the things we’re doing, or promoting personal autonomy as the highest ideal.

So let’s talk about that. The parts of the book that I found most challenging are when you write about abortion, childcare, gender identity and even baby formula as examples of people seeking “independence of the self from the body.” For example, you have some pointed critiques of the pro-choice movement, writing, “The celebration of abortion is so vehement in the progressive world that it sometimes feels like pregnancy itself is suspect, whether wanted or not.” Let me ask, are you pro-choice?

I’m definitely pro-choice in that I believe that abortion should be legal. But I think that abortion has become part of the way that our culture emphasizes the freedom of individuals over our communal obligations. So I talk about in the book how eager corporations are to pay for people to get abortions, or pay for you to drive across state lines to get an abortion, or pay for people to freeze their eggs. Again, I think people should be able to get abortions, but the fact that corporations are so eager to support that, and are kind of reluctant to give people family leave and support people in their pregnancy and child-rearing — to me, that means that there’s something more going on. The human ideal in this culture is one who is unencumbered by family, certainly by the dependency of children, or pregnancy. Creating this new life is not what this capitalist culture holds up as the ideal. The ideal is the individual, freely choosing. So it’s not that people shouldn’t be able to have abortions, but the celebration of it as a kind of empowering, choice-oriented thing is a symptom of this culture.

A protester holds a sign saying “Abortion bans are against my religion” at the May 2022 Jewish Rally For Abortion Justice in Washington, D.C. (Anna Moneymaker via Getty)

In a similar vein, you write, disapprovingly, that, “American culture and finances dictate that our biological reproductive lives should only interfere minimally in our economically productive lives — or our self-actualization, for that matter. So our babies are often fed formula, sleep trained by any means necessary, and sent to paid care-givers at the earliest possible opportunity.” Feminists, led probably mostly by Jewish women, have fought for decades for a world in which biology is not destiny in the sense that it shouldn’t define women’s roles in the world. But are you suggesting that in some ways, they have to surrender that? That women ideally should eschew childcare and careers and be home with their children?

We’ve built a society where women can’t do that, even if they want to. It’s kind of like Shabbat: In the name of not having to keep Shabbat, you’ve created a situation where it’s really hard to keep Shabbat. So if a woman in our culture wants to have lots of children and has the time and ability to stay home with them when they’re young, that’s really hard to do unless you’re rich. Otherwise you have to work and then pay most of what you make at work to daycare, even though that’s not what anybody wants. So we haven’t created a society that supports that as a real option for people, and I think there’s a lot of grief that comes out of that.

I’d also like to ask about transgender and gender fluidity. There’s a section of your book in which you ask, “What does it mean for a society as a whole if more and more people are removing their breasts”? And you suggest that the decisions to do so, which would presumably include transgender men, “point to a deep-seated spiritual grief and alienation.” Can you unpack that for me?

For some people, and I’ve known these people, it feels absolutely essential to change their body to match their internal sense of their gender. I would never criticize an individual’s decision to have an abortion or change their body to conform to their gender identity. I think these procedures should be legal and accessible. I also think that the prevalence and even celebration of these things in our culture are some (of many) indicators of an ethic or theology in which the individual self is a free-floating entity, separate from our bodies, our communities and the earth. This alienation as a whole is responsible for a lot of collective grief and, I believe, for our inability to live in sustainable relationship with our ecosystems. Abortion and gender surgeries are not the cause (or even a cause) of this alienation — if I were to point a finger at any overarching cause, it would be our immersion in screen-based, web-based technologies.

It’s not my role to agree or disagree with your book, but I did wonder as a journalist if you were citing extreme positions on the secular left and attributing them to the liberal mainstream. For example, you quote one young man who complains that “his pro-choice friends see adoption as a harmful phenomenon because it can serve as an enabling agent” for the pro-life movement. Honestly, I have never heard a pro-choice friend denigrate adoption. I guess I am defending the journalistic notion that you shouldn’t compare the worst or most extreme tendencies of one group to the best tendencies of another group.

I don’t know if the left, in general, disparages adoption. This was this one particular person. But I do feel like when people are talking about abortion and pro-choice politics, people are a little bit wary of the topic of adoption, because it is used by pro-lifers to say, well, you don’t have to have an abortion.

But I do think it’s useful to look at the extremes, in order to see the vector of where a trend or idea might end up. My experience with Unitarian Universalism in general was that, while most of the left in this country is not as left as UU, this is what happens if you completely give up all traditions, all sense of accountability to the past. So I know that’s not the norm. Most people have never even heard of Unitarian Universalism. But when you look at the extreme of something, it kind of helps you see the direction we may be headed in.

As I’m reading your book, I’m saying, “Wow, she’s writing about that middle ground between modernity and tradition, obligation and autonomy. That’s Conservative Judaism, with a large C.” And yet you are studying toward the rabbinate at ALEPH, which is part of the Renewal movement, which is a very liberal and innovative movement and which I don’t associate with the kind of rigorous religious obligations and “shoulds” that you write about. Tell me a little bit about that decision, or if I am wrong in terms of the kind of rabbis it’s creating.

You’re exactly right about the kind of rabbis that ALEPH is creating. They are all about expanding the traditions and reinterpreting halacha [Jewish law] and all of that. But there are a number of rabbis who are teachers there who I would say are more traditionalist, and Zalman Schachter-Shalomi [the late founder of ALEPH] himself was coming out of Orthodoxy and was very carefully opening up a tradition that he was definitely not abandoning. The reason why I ended up at ALEPH was because I was working full time as a minister, and I was writing books and I was raising a family, and so I had to study part time. There was no way I could go full time to [Conservative Judaism’s Jewish Theological Seminary], and [ALEPH] would allow me to study part time. And in some ways it’s been a good fit for me because the mystical orientation of Jewish Renewal is something that really resonates with me.

What do you intend to do with your rabbinical degree? Are you interested in another pulpit?

I’m so done with the pulpit! [laughs] I mean, I’m glad that I had that experience, but it’s so hard.

I’m probably just going to continue doing what I’m doing now. I’m now trying to recreate a career for myself doing freelance versions of different components of clergy work. Writing, guest-preaching, one-on-one spiritual work.

I’m also thinking about a wider program that’s sort of the inverse of Footsteps [an organization that helps people who have left haredi Orthodox Judaism find their footing in the secular world]. What would it be like to help people escape from the oppressiveness of secular modernity, and find the freedom of the religious and communal life?

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.