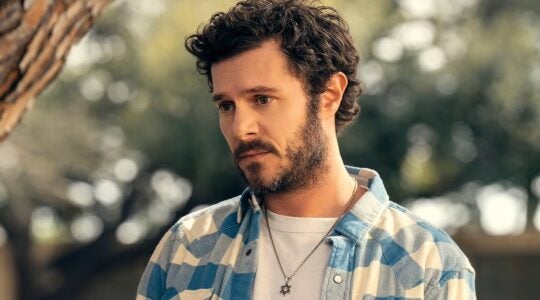

Ami Horowitz, director of the film “U.N. Me,” next to a U.N. car in Cote d’Ivoire. (Frank Publicity)

NEW YORK (JTA) — Call it Michael Moore meets Sacha Baron Cohen.

A pro-Israel activist is hoping that his documentary on the United Nations — to be released nationwide on June 1 — brings focus to what he says is the world body’s global ineffectiveness.

One of the more rambunctious scenes in “U.N. Me” comes from a lull in deliberations at the controversial 2009 Durban Review Conference in Geneva, a parley headlined by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and boycotted by Israel, the United States and others because of its obsessive focus on the Jewish state.

In the clip, an American in a dark suit and tie mounts the podium and seizes the microphone.

“You people should be embarrassed and ashamed,” filmmaker Ami Horowitz announces to the handful of delegates scattered about the hall. “You have squandered the opportunity the world has given you. This is a perverse example of what it was meant to be.”

The conference already had been somewhat of a diplomatic zoo, with myriad protesters — a disproportionate number of them Jewish — disrupting the proceedings and causing a ruckus in the hallways. With security heightened, Horowitz was whisked from the room within seconds.

But standing in the near-empty press gallery was Horowitz’s partner, Matthew Groff, who captured the incident on tape (as did JTA). The footage now forms the climax of the scathing documentary written, directed and produced by Groff and Horowitz.

Horowitz’s Geneva stunt is a move plucked from the playbook of the documentarian Moore, whose screen persona of the everyman trying to get straight answers from the powerful pervades his critically acclaimed work in films such as “Bowling for Columbine” and “Roger & Me.”

But will the left-leaning Moore’s trademark style wow viewers of a documentary taking aim at an organization that has long been a punching bag for the right?

Horowitz, a former investment banker and avowed conservative, says the film is neither liberal nor conservative. Indeed, in what may wind up being a savvy directorial decision, the film never mentions what many consider one of the most egregious examples of the U.N.’s moral blindspot: a relentless focus on Israel.

Instead, Horowitz keeps the lens trained on U.N. failures in areas generally cherished by liberals: peacekeeping and human rights.

He travels to the African nation of Cote d’Ivoire, where he reports on a little-known incident in which a contingent of French U.N. peacekeepers fired on protesters. He interviews Nobel laureate Jody Williams, whose report on Darfur for the U.N. Human Rights Council was nearly blocked by the very body that commissioned it. And he reviews the details of better-known examples of U.N. wrongdoing, such as sexual abuse allegations by peacekeepers and the atrocious Oil for Food Programme that served mainly to enrich Saddam Hussein.

“Almost anybody who is a liberal thinks it’s a liberal movie, and everybody who is conservative thinks it’s a conservative movie,” Horowitz said. “People don’t know [U.N. reform] is a conservative cause.”

If Horowitz’s style owes much to Moore — a man he describes as his “friend” — he also acknowledges a debt to another character of the big screen: Borat, the fictional and clueless Khazaki journalist made famous by Cohen.

Horowitz routinely presents himself as a credulous buffoon, eagerly accepting the assurances of an Iranian official that his country is not making nuclear weapons and agreeing with U.N. disarmament chief Sergio Duarte’s assessment that despite Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s repeated hostile declarations against Israel, the Iranian president’s true intensions cannot be divined.

The routine succeeds, Borat-syle, in making several interviewees look silly. In a segment on the U.N’s failure to stop the killings in Darfur, Horowitz asks Sudan’s ambassador to the United Nations why Sudan stones gays after the first offense but lesbians only after the fourth.

“No, no, no,” the ambassador corrects him. “Woman, if she is married, she will be stoned immediately.”

Earlier in the interview, Horowitz informs the ambassador that before learning of the situation in Darfur, he had thought the Janjaweed was a strain of Sudanese marijuana.

Horowitz says he was moved to make a film about the United Nations after watching “Bowling for Columbine,” Moore’s documentary about guns and violence in America.

“I saw his movie and [I thought], if I want to get my point across, this is the best way to do it,” Horowitz said.

Financed in part by the conservative telecommunications executive Howard Jonas, “U.N. Me” premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam in 2009. Jonas also helped Horowitz penetrate the halls of power.

Horowitz screened the film for Dick Cheney at the former vice president’s home in Virginia, and for media executives Rupert Murdoch and Roger Ailes in New York. According to Horowitz, Murdoch liked the film and wanted to distribute it, but Ailes warned him that supporting the film would be tantamount to declaring war on the United Nations.

Murdoch, Horowitz recalled, replied that Ailes’ FOX News is already at war with the world body.

“The whole idea of the movie is based on the idea of activism,” Horowitz said. “I’m not trying to tell an impartial story. The only thing I’m responsible for is the truth. I have no responsibility beyond that. I don’t have to show both sides of anything. I have a point of view and I’m trying to prove it.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.