NEW YORK (JTA) — New York City’s gay pride parade on Sunday was full of highlights. The NBA and WNBA became the first professional sports leagues to march. A Syrian refugee whose life was threatened by an ISIS operative served as a grand marshal. Even Hillary Clinton made a surprise appearance.

Also, the parade brought out a new gun control group, Gays Against Guns, inspired by the shooting this month at an Orlando nightclub that left 49 dead.

The deadliest such attack in U.S. history has thrust the LGBTQ community into the national spotlight for weeks. The shooting also happened in the middle of LGBT Pride Month, which has been officially recognized by U.S. presidents since Bill Clinton signed a proclamation in 2000.

Why June, you ask? The monthlong celebration is technically a tribute to the Stonewall riots, which galvanized the LGBT-rights movement following the police raid of Greenwich Village’s Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. (Kicking off a tradition, the first pride parade happened the following year.)

From Stonewall to last year’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling legalizing same-sex marriage in all 50 states — also in June — Jews have been at the forefront of the fight for LGBTQ rights. Here are nine of the most influential Jews who have helped make LGBTQ issues visible and are still working to enact change.

Jazz Jennings

Jazz Jennings posing with the Trevor Project Youth Award during TrevorLIVE LA 2015 at Hollywood Palladium in Los Angeles, Dec. 6, 2015. (Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images for Trevor Project)

Jazz Jennings — who was born with a longer, “very Jewish” last name — has accomplished a lot for a 15-year-old: She’s a reality TV star, a published author and a face of Johnson & Johnson’s Clean & Clear campaign. (She was also the youngest grand marshal of New York’s Pride Parade on Sunday.)

It probably helped that she got a head start in the public eye at the age of 7, when she became one of the youngest people to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria — a condition in which a person experiences clinical distress with the gender she or he was assigned at birth (in Jennings’ case, male).

Jennings’ book and popular TLC show “I Am Jazz,” which focus on her life and obstacles as a trans teen, have made her the unofficial face of America’s transgender youth.

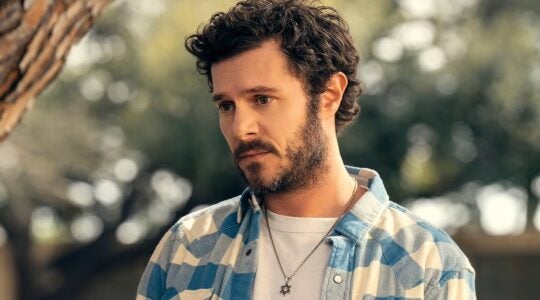

Barney Frank

Rep. Barney Frank, who served in Congress from 1981 to 2013, at his office in Washington, D.C. (Michael Chandler)

Before publicly coming out in 1986, Barney Frank admitted he was gay to then-Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill.

“I’m sorry to hear it,” O’Neill said. “I thought you might become the first Jewish speaker.”

Frank, of course, never became speaker — but his coming out during the height of the AIDS crisis (and becoming one of the first openly gay U.S. congressmen) remains a big piece of his professional legacy. In addition to passing prominent legislation like the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, he became the first person to marry someone of the same sex while serving in Congress in 2012.

Fran Drescher

Fran Drescher at a charity event in Vienna in 2010. (Wikimedia Commons)

Fran Drescher is known for happy things, like her signature nasal laugh and comedic roles in shows like “The Nanny.” But her personal life took what appeared to be an unfunny turn when she divorced her husband of 20-plus years, Peter Marc Jacobson, and he came out as gay.

But here’s what happened: Drescher stayed close with Jacobson, and the pair produced a show based on the ordeal, “Happily Divorced.” She was so inspired that she lent her voice in 2010 to the campaign for legalizing same-sex marriage in New York (it became legal in 2011). Then, in 2012, she became an ordained minister just so she could wed same-sex couples.

“Even though I am Jewish, I take no offense at being a minister or called Reverend Drescher,” she told The New York Times. “Love is love. I’m not a divisionist; I am a uniter.”

Tony Kushner

Tony Kushner attending the “Mike Nichols: American Masters” world premiere at The Paley Center for Media in New York City, Jan. 11, 2016. (Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty Images)

If you surveyed Americans about the most important works of art symbolizing the LGBTQ community’s struggles and triumphs, Tony Kushner’s play “Angels in America” would likely be near the top of the list.

The epic two-part opus, which examines the complexity of gay life and relationships in the 1980s, premiered in 1991 and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, the Tony Award for best play and the Drama Desk Award for outstanding play.

It’s still produced around the world and has been made into an HBO miniseries and an opera — in other words, it has been a prominent part of the American cultural lexicon for more than two decades.

But Kushner didn’t stop and rest on his laurels. In addition to writing screenplays for films like “Munich” and “Lincoln,” he has since written defenses of gay idealism and spoken publicly about the AIDS crisis. Although his criticism of Israeli government policies has riled many in the pro-Israel community, he also insists, “If I were to imagine laying down my life for any country, it would be Israel as much as any other.”

Abby Stein

Abby Stein, seen after leaving the Hasidic community (Screenshot from YouTube)

“In the community that I was raised in, Trans did not exist, neither was it ever discussed,” Abby (nee Srully) Stein wrote on her blog last year.

Stein’s community was a Hasidic Jewish one — in fact Stein, from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is descended from a long line of influential Hasidic rabbis. That made her decision to leave the haredi Orthodox community last year even more shocking.

Stein’s two transitions — from out of the Hasidic world and from man to woman — made headlines from the New York Post to the Daily Mail.

“My main goal is to get people to talk about it,” she said. “I don’t care how hateful the reaction might be within the Orthodox community.”

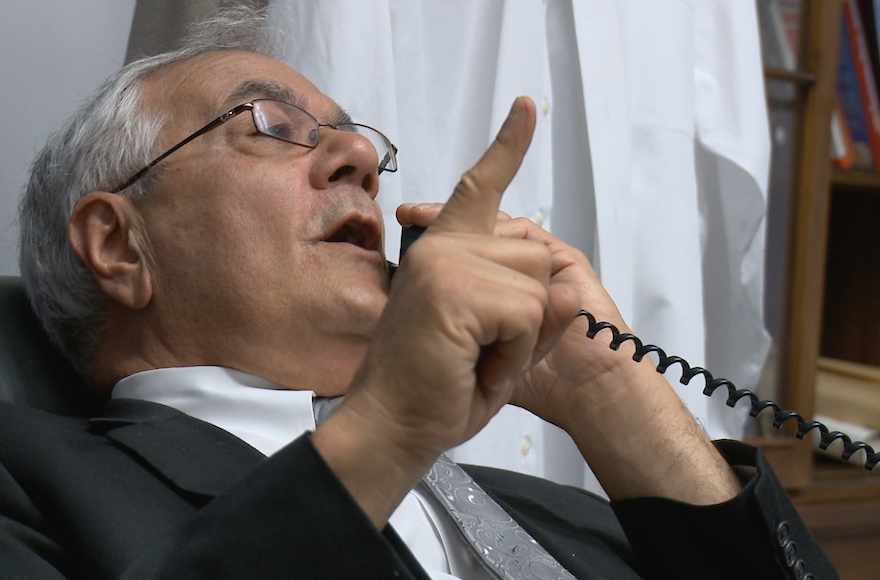

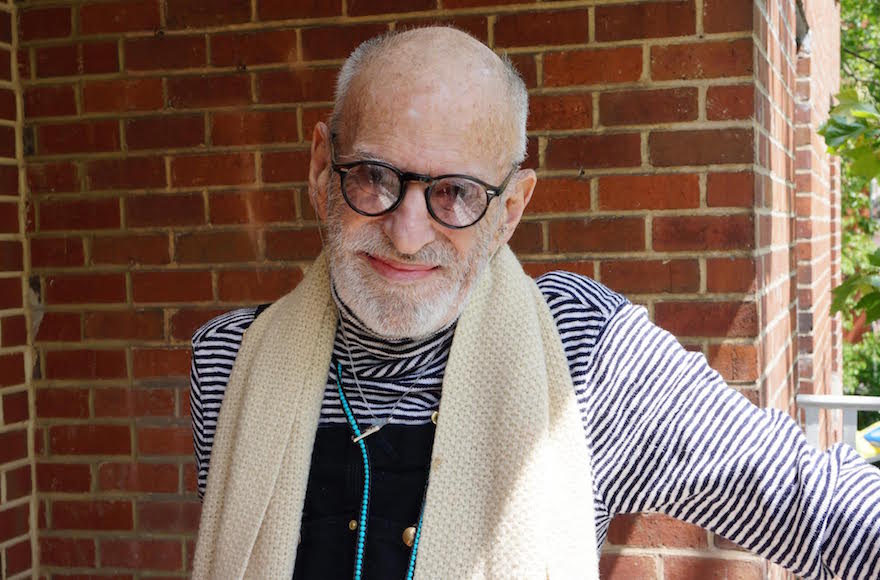

Larry Kramer

Larry Kramer is considered one of the most important figures in the history of LGBTQ activism. (Courtesy of HBO)

Writer Larry Kramer has been called the “angriest man in America.” Fortunately he has channeled most of that anger toward fighting AIDS and combating anti-LGBTQ forces in American society.

His 1978 novel “Faggots,” about the hedonistic lifestyles of many gay men in New York at the time, earned him enemies both gay and straight. His semi-autobiographical 1985 play “A Normal Heart” — inspired by a visit to the Dachau concentration camp — portrayed an angry gay activist fed up with the more polite strategies adopted by his colleagues.

Kramer was a co-founder of the massively influential Gay Men’s Health Crisis, now one of the biggest AIDS service organizations in the world, but was forced out due to his confrontational demeanor and went on to found the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP.

Kramer will be remembered as one of the most important figures in the history of LGBTQ activism. And his worldview was undoubtedly shaped by his Jewish identity.

“In a way, like a lot of Jewish men of Larry’s generation, the Holocaust is a defining historical moment, and what happened in the early 1980s with AIDS felt, and was in fact, holocaustal to Larry,” Tony Kushner said in 2005.

Rabbi Denise Eger

Rabbi Denise Eger, center, reading Torah during her installation as president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, March 16, 2015. (David A.M. Wilensky)

When Rabbi Denise Eger became the president of the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis last year, she did not become the first openly gay or lesbian clergy member to lead a rabbinical group. That honor belongs to Rabbi Toba Spitzer, who became president of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association in 2007.

But Eger’s accomplishment was just as momentous, if not more so, since the Reform movement is by far the largest Jewish denomination in the U.S., and the Central Conference of American Rabbis is the largest and oldest rabbinical organization in North America.

Eger’s professional and activist career arc — from coming out to the L.A. Times in an article in 1990 to founding Los Angeles’ pioneering LGBTQ-friendly Kol Ami synagogue in 1992 — closely parallels the arc of LGBTQ rights in America.

And she knows it. “I smile a lot — with a smile of incredulousness,” Eger told The New York Times last year.

Evan Wolfson

Attorney Evan Wolfson is recognized as the architect of the modern marriage equality movement. (Wikimedia Commons)

In recent years, many celebrities have lent their voices to the push for LGBTQ rights, particularly the fight for same-sex marriage. But the man recognized as the architect of the modern marriage equality movement is a Jewish lawyer named Evan Wolfson.

As a Harvard Law student in 1983, Wolfson wrote a thesis on the legal basis for same-sex marriage, well before the topic had been seriously considered anywhere around the world. His book “Why Marriage Matters: America, Equality and Gay People’s Right To Marry” earned him a spot on the Time 100 list in 2004. The Freedom to Marry nonprofit, which he formed in 2003, would go on to be credited with driving the Supreme Court’s decision last year to protect same-sex marriage in every state.

Wolfson’s successful strategy was to change the way people think about same-sex marriage — to convince them that it was a matter of constitutionally protected freedom.

“Marriage is not defined by who is excluded by it,” he wrote in 2011.

Rabbi Steven Greenberg

Rabbi Steven Greenberg, seen in 2014, was the first openly gay Orthodox rabbi and has propelled the conversation about LGBTQ acceptance in the Orthodox community. (Wikimedia Commons)

Boston resident Steve Greenberg was the first openly gay Orthodox rabbi, coming out in 1999. This was no easy task, since being a gay member of the Orthodox community was and is still not a fully accepted idea.

When he first told one of his teachers he was gay, he was asked: “Stevie, have you gotten help?”

So it was a momentous occasion — and perhaps partial vindication for his work within his community — when a group of Orthodox rabbis participated last year in a discussion about the treatment of Orthodox LGBTQ Jews.

Greenberg, who holds an ordination from Yeshiva University’s Orthodox rabbinical seminary, helped found Eshel, a national Orthodox LGBT support and education organization. He has not been hired by an Orthodox congregation, but he has propelled the conversation about LGBTQ acceptance in the Orthodox community. His book “Wrestling with God and Men: Homosexuality in the Jewish tradition” won the Koret Foundation’s Jewish Book Award in 2005.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article incorrectly spelled Rabbi Toba Spitzer’s name as Tova Spitzer.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.