May 2014, 7:00 AM, Amman airport. I am returning to Jerusalem from a celebratory conference that began with so much promise. Two Israeli doctors developed a hearing aid operated by solar battery and contributed it to the Jordanians, who suffer high incidence of infant deafness due to tribal in-marriage. If treated before age 3, there is hope for normal speech and a normal life. Heretofore, families of deaf children routinely tossed hearing aids when the battery ran out, long before three years. At the concluding session, we ask if recipients will know it is a gift from Israel.

“Not possible,” we are told.

“What about the public reception in Amman to announce the project? Will the publicity acknowledge Israel?”

“No, it would spoil matters,” is the reply.

I suppress the urge to walk out.

At the airport, I look up at the sky, bluest of blues, reminding me of Jerusalem in1961, as I awoke each morning to feed my infant son. I’ve not seen such a sky in years. Worse, as our plane approaches Israel 45 minutes later, I see the map of Israel laid out perfectly in the sky – in the shape of a thick pollution cloud. I reach Jerusalem at 9 a.m. and the city is gray. At 10:15, the sun breaks through, yet the sky is not blue as in Amman; it’s blue-gray. Suddenly I realize I’ve been looking at the sky through a pollution cloud for a long, long time.

I fell in love with Jerusalem on High as a young girl growing up in a religious Zionist home. Emissaries from pre-Israel Palestine would stay at our home in Seattle, Washington, a great honor. A precious black velvet painting of the Western Wall, the Kotel, hung in the hallway. ‘Uveneh yerushalyim,’ we prayed, in the words of the Grace After Meals, “and Jerusalem will be rebuilt.” Who would imagine…

I fell in love with earthly Jerusalem after ‘48, a teenager singing B’nai Akiva songs, devouring “Exodus” by Leon Uris. At 19, I came as a student in a teachers training institute. The extraordinary Nechama Leibowitz was our teacher. Long before feminism, a word she eschewed, she opened my eyes to women’s in-depth rabbinic learning.

On a tour of the Judean Hills, our guide divided the 29 of us into two groups. “You,” he pointed to my group, “are standing with young David, and you,” pointing to the other, “will stand on that hill with Goliath.” An electric shock ran through me, the visceral sensation of connecting to Jewish history. Jerusalem, ir Daveed, city of David; I got it.

The continuous interweaving of Jewish past and present informs that year –and the rest of my life.

I returned to Israel in 1961, on my husband’s Fulbright scholarship. A magical year, wandering Jerusalem streets, reading history in street signs, listening to friendly people volunteer advice how to raise my little son in the stroller. My husband Yitz and I promised ourselves to return on aliyah within two years, a promise repeated shamelessly every two years.

One afternoon, I leave my handbag—keys, money and passport—on a ledge at the busiest bus stop on Ben Yehuda. After four hours I remember and rush back. Despite the many hundreds of people who passed by, there it sits. I recall the words of Nechama: “Why does Megillat Esther repeat three times, “And they [Persia’s Jews, victoriously defending themselves] did not put their hands on the spoils”? In 1948, she understood. “To acknowledge the nobility of their restraint. When Israel took control of the neighborhood of Baka, the government forbade entering hastily abandoned Arab homes or taking possessions. And no one did.”

One day in Meah Shearim, I stand riveted, watching a young mother buy a pretzel at a kiosk and bend down to feed her small son, kipah tied with ribbon under his chin. I sense he is just learning to speak. She holds out the pretzel in front of him: “Baruch,” she begins to instruct him in the blessing and he repeats each word after her. With the last word, “mezonot,” she gives him a hug and puts the pretzel into his hand to munch. My eyes well up, something about holiness and covenant between generations.

Summer ’69. With the exuberant reunification of Jerusalem still fresh, and with ancient sites and new neighborhoods to visit, we return with five children. We did not give a moment’s thought as to who had lived in these homes and villages, who had planted these trees and gardens. They were the enemy and that was that.

We return again in ’74, a sad year in Israel’s history, following the Yom Kippur War and its heavy loss of life, and a defining one for our family as we absorb the national psyche after war. Yet our children thrive in school and in the language of our people.

Erev Shavuot, ’75. I realize I’d forgotten the boys’ re-soled shoes and rush to the shoemaker at noon. He’s pulled down his tin gate. “Please, please, their Shabbat shoes,” I appeal to him. Up goes the gate as he recites, “And if your brother falls, you must lift him up.” [Lev: 25:35] A shoemaker with a Jewish soul/sole.

Thereafter we visit Israel every year, for conferences, family celebrations, our children’s post-high school gap years, and then multiple visits a year as they make aliyah and produce grandchildren. In 2002, we come to bury a child.

As our personal commitment to Jerusalem deepens, we also become more aware of its political complexities. In 1989, I exit the new Rejwan building in town and an Arab construction worker makes an obscene gesture and glares at me. I had lived in my bubble of obsequious waiters and Old City shuk salesmen and was not aware of the pending intifada. I resolve to work on dialogue, yet also worry that this fellow may have stuffed the building’s core plumbing to vent his rage.

- We come for the brit of our grandson Eran, held in a room overlooking the Old City. He is the descendent of generations of rabbis, also of Levites on my side and Kohanim on my husband’s. Sitting there, I wonder: is this the first Jerusalem brit on both sides of our family since the destruction of the Temple? I don’t live in Israel as yet, but a feeling of “we’re back” sweeps over me, along with the joy of a new soul entering the covenant.

- I walk through Baka with women from my Jewish-Palestinian dialogue group, four years of talking in New York and now a visit here. The Jerusalem stone “Arab homes” are gorgeous, stately. Yet, four Palestinian women, arms linked, walk behind me, talking softly. I wonder. Did any of these homes belong to their families? How do I handle that? That they followed the anti-Semitic Mufti, joined the enemy and attacked first is not the whole answer. No wonder they hate us so much, dialogue or not. Was our four years of polite conversation about two states artificial, or even a dupe? Perhaps. Like everything else about Jerusalem, the answer will never be a simple one.

- Walking alone late at night in the rapidly gentrifying German Colony, I hear quick footsteps behind me. I feel relief when I see that he is black, sub-Saharan black. From Ethiopia. My brother.

- On my way to my daughter’s apartment on Joshua Ben Nun street, I note the unfamiliar route and say to the driver, “Wrong way, I think.” He claps his head, apologizing for his mistake. “Oy, I thought you said Caleb Ben Yefuneh.” He turns off his meter and takes me to the street named for Caleb’s biblical partner, Joshua Ben Nun.

- The Jewish Policy Planning Institute holds its conference at Mt. Zion Hotel, carved into the hillside, with majestic views of old and new Jerusalem. At 4 a.m. I am awakened through double glazed windows by the muezzin’s persistent call to prayer, amplified by loudspeaker. Would any other democracy tolerate this nightly assault? The next morning, I learn that chef Moti’s mother, who lived nearby since birth, just moved from this city of peace to Tel Aviv in search of uninterrupted sleep.

- I’ve spent 48 hours at Shaare Zedek Hospital, microcosm of messianic times. Excellent caring doctors and nurses, maintenance staff, patients, relatives, children — all in a place free of religious, racial and color differences. My left-wing friends should walk these and Hadassah’s halls and rethink their “apartheid” criticisms. Never mind. I know that facts won’t change their minds. But then again, on my visit to Terem Romema infirmary, I am served early one Friday morning by three gracious men — receptionist Ahmed, Doctor Fahid, and radiologist Abdul. I must learn to qualify my criticisms and refer to “some Palestinians,” “some Israeli Arabs,” and even “some leftists.”

- Walking to Angel’s Bakery to buy onion sourdough bread, baked Mondays and Thursdays, I hear sirens. I stop in my tracks and, like other Jerusalemites, strain to hear whether it is one ambulance or several. One. I bless God and continue on my way.

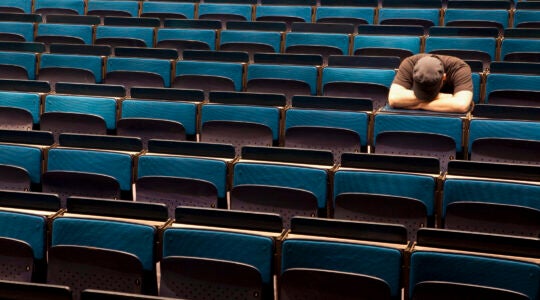

- Once again, I am grousing about the pollution, blue-gray Jerusalem skies on a good day. My friend Naomi who moved from Manhattan to Yemin Moshe chastises me: “I’m surprised this bothers you so much. This is the greatest place to be. Look what we have accomplished here, what we have given to the world, solar hearing aids and autonomous driving. With the pollution comes all the advancement, so you can envy their blue skies but remember what we’ve achieved. And the pollution? We’ll fix that, too.”

Blu Greenberg, founder of JOFA, the Jewish Feminist Orthodox Alliance, is a poet, writer and lecturer and lives in Riverdale.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.