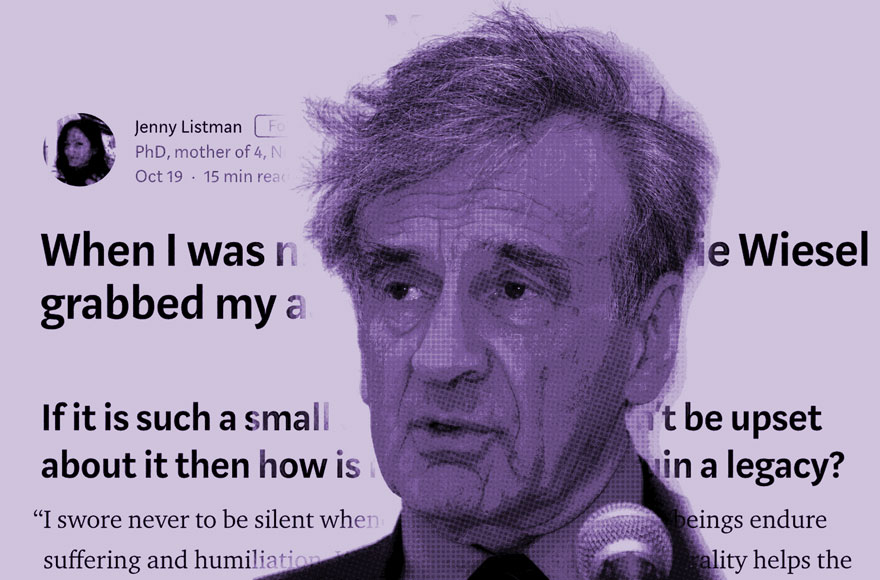

NEW YORK (JTA) — When I read the headline of Jenny Listman’s Medium piece — “When I was nineteen years old, Elie Wiesel grabbed my ass” — I decided not to click on it.

It wasn’t because of any judgment I passed on her or the veracity of her claim. But the bluntness and clarity of her headline was, in the worst of ways, transporting — or as the youth like to say, triggering.

Not having even read it, I knew I believed it, believed her. I believed that as a 19-year-old attending a Jewish fundraiser in 1989, she was fondled by the Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor as they posed for a group photograph.

Now I’d like to clarify that I don’t think that just because I believe something, there is an obligation for news outlets like JTA to publish a story about it. We need to be thoughtful before we publish anything, especially something so serious as an allegation of unwanted sexual contact. We need to confirm certain basic facts: that the accusers are who they say they are, that they were where they claimed to be — and, when possible, get a response from the other side.

But as a woman, whenever I can, I make the choice to believe victims. I know how important it is to stand in solidarity with other women when so often our experiences are less likely to be believed. What has been especially surprising about the rise of #MeToo, the popular internet campaign that has victims of sexual assault and harassment sharing their experiences, has been the incredulous response from men. We have been telling our experiences for months and years, yet men still insist they did not know.

From my own experiences and what I’ve heard from other women, queer and non-binary people, I know just how common sexual harassment and assault are. They are carried out by strangers in the street and by men we believed in, who we thought were “good guys.” Which is why these allegations are never surprising, to me at least.

Another thing that was not surprising to me was the propensity — especially by men (and of course by some women) — to doubt Listman’s story and put her down for telling it.

Even in Listman’s own tale, the response from her then-boyfriend is particularly telling: When she tells him about Wiesel squeezing her behind, he responds with incredulity. “He must have had his hand on your waist,” he says. “Are you sure?”

Women’s experiences of pain, emotional and physical, are often doubted or downgraded. Recent studies show that women are 13 to 24 percent less likely to be treated with opioids for pain than men, and that they have to wait longer to receive pain medication in emergency rooms. Our pain, quite literally, is simply taken less seriously.

I’ve seen people dissecting Listman’s pain and trauma, so clearly depicted in her Medium piece, in the most ungenerous of ways. They’ll say that she couldn’t have been so traumatized by an action as minor as having her butt squeezed. It seems to me just another case of us doubting women’s pain.

I worry that in reporting the onslaught of stories on sexual assault, harassment and rape, we all become accountants of pain or gravity. Stories like those of Harvey Weinstein and James Toback, of Bill O’Reilly and Terry Richardson, offer gruesome accounts of serial harassment, abuse and assault. There is wide consensus that these serial predators should get what they deserve. But if someone carries out an act of sexual assault only once, is it any less of a violation? In only reporting the “major” offenders, are we saying the isolated incidents are somehow OK?

According to a federally funded study, the prevalence of false reporting in cases of sexual assault is between 2 and 10 percent. Despite those incredibly low numbers, according to the study, survivors who come forward often “face scrutiny or encounter barriers” from investigators. You know what has a high likelihood? Women not reporting assault and men never being convicted for sexual assault.

As to the conversation about Elie Wiesel’s “legacy” — the legacies of great men and women are always more complicated than we are comfortable admitting. And the legacies of men with power are often intertwined with abuses of that power.

There is nothing “Jewish” about the scandals surrounding Weinstein or Toback, or the allegation about Elie Wiesel — except to the degree that the Jewish media claim them as members of the “community.” Theirs are stories about men in positions of power abusing the less powerful or the powerless. That’s what binds the narratives pouring forth from women on Facebook and the mainstream media. We should be able to acknowledge the legacy of a man like Wiesel without ignoring the possibility that he was flawed.

But the comments about protecting the legacy of Elie Wiesel are, intentionally or not, upholding another legacy: the legacy of believing men over women and sweeping the truths of women under the carpet.

(Lior Zaltzman is the social media editor for 70 Faces Media, JTA’s parent company.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.