Politically correct critics, who gleefully squelch free speech in other contexts, are yelling “censorship” because the American Jewish Historical Society of the Center for Jewish History cancelled two events perceived to be biased and anti-Israel. I have not read the nixed play, so, unlike, most people these days, I withhold judgment. I do, however, defend an institution’s right to draw red lines — creating a no-go zone. I also want Jewish institutions to have blue-and-white lines — identifying events and values it wishes to promote. Critics call it censorship; we used to call it good judgment.

Years ago, when I worked at a summer camp, I was the go-to guy when kids were suspected of hiding drugs. Even though I had never tried any of the stuff, I was better than my more “experienced” peers at finding kids’ stashes. Also, when the kids yelled that we were searching their possessions “without a warrant,” as an American historian-in-training I could explain that the camp was private property. Constitutional limits on government searches — which I supported — didn’t apply.

This critique applies to the overused word “censorship,” too. That word is modified most frequently by the word “government.” I oppose government censorship ardently. I want to fight issues out in the free marketplace of ideas. We cannot trust the government to decide which ideas are acceptable and which are not — beyond truly violent-inducing statements.

Jewish institutions are allowed to decide what they stand for — and who they stand against.

Moreover, open places committed to free thought and inquiry, like universities used to be, should not favor certain political viewpoints or censor others. But Jewish institutions are allowed to decide what they stand for — and who they stand against. It is legitimate to shun organizations that support Israel’s destruction — which would kill millions of Jews, or organizations that support Palestinian terrorism.

The process of drawing lines is an important exercise in organizational identity-building. Deciding whom you reject is a way of deciding who you are — and who you wish to be.

The same set of views can be appropriate or inappropriate in different institutions, depending on the institution’s mission. For example, an anti-Zionist should be able to earn a Ph.D. in Jewish Studies. I might regret the person’s politics, but Jewish Studies is a serious academic endeavor, not a Jewish cheerleading squad. Departments, therefore, must judge candidates on their scholarship, not their politics.

At the same time, the Jewish Theological Seminary should not ordain anti-Zionists as Conservative rabbis. Rabbis are not neutral academics. They are supposed to champion certain ideals, and the Conservative movement has long believed that Israel “plays an essential role in our present and future.” An anti-Zionist Conservative rabbi is like a Catholic priest who rejects Jesus — that’s how central Zionism has been to the Conservative movement. The JTS would be violating its central mission.

No one can claim that in 2017, the anti-Israel and even anti-Zionist line is not heard repeatedly, in America, in New York, within the Jewish community. Given that, I do not see why precious Jewish communal resources should be wasted boosting anti-Zionists and those who undermine the unity of the Jewish people.

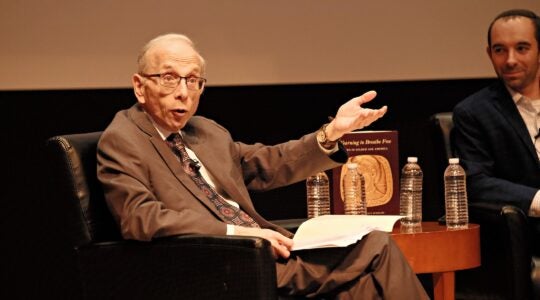

Sadly, the most frequent question non-Israeli Jews ask me when they hear that this spring I am publishing an update of Arthur Hertzberg’s classic Zionist anthology, “The Zionist Idea” (which I am calling “The Zionist Ideas”), is, “Will you include anti-Zionists, too?” I reply: “When feminist anthologies include sexists, LGBT anthologies include homophobes and civil rights anthologies include racists, I will consider anti-Zionists.” This Jewish need to include our enemies when telling our own story tells its own story.

Yes, I used the word “enemies.” We have critics. We have enemies. We have fellow travelers and enablers who collaborate with people who endorse mass Jewish murder in their fight to destroy Israel. Learning how to distinguish among these different people isn’t censorship — it’s just common sense — and basic loyalty.

Gil Troy is a professor of North American history at McGill University and author, most recently, of “The Age Of Clinton: America In The 1990s.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.