(New York Jewish Week) — The true story of a formerly Hasidic Baltimore man who encouraged Jews to convert to Christianity during the Holocaust serves as the unlikely jumping-off point for a new, Yiddish-language play beginning previews this week in Manhattan.

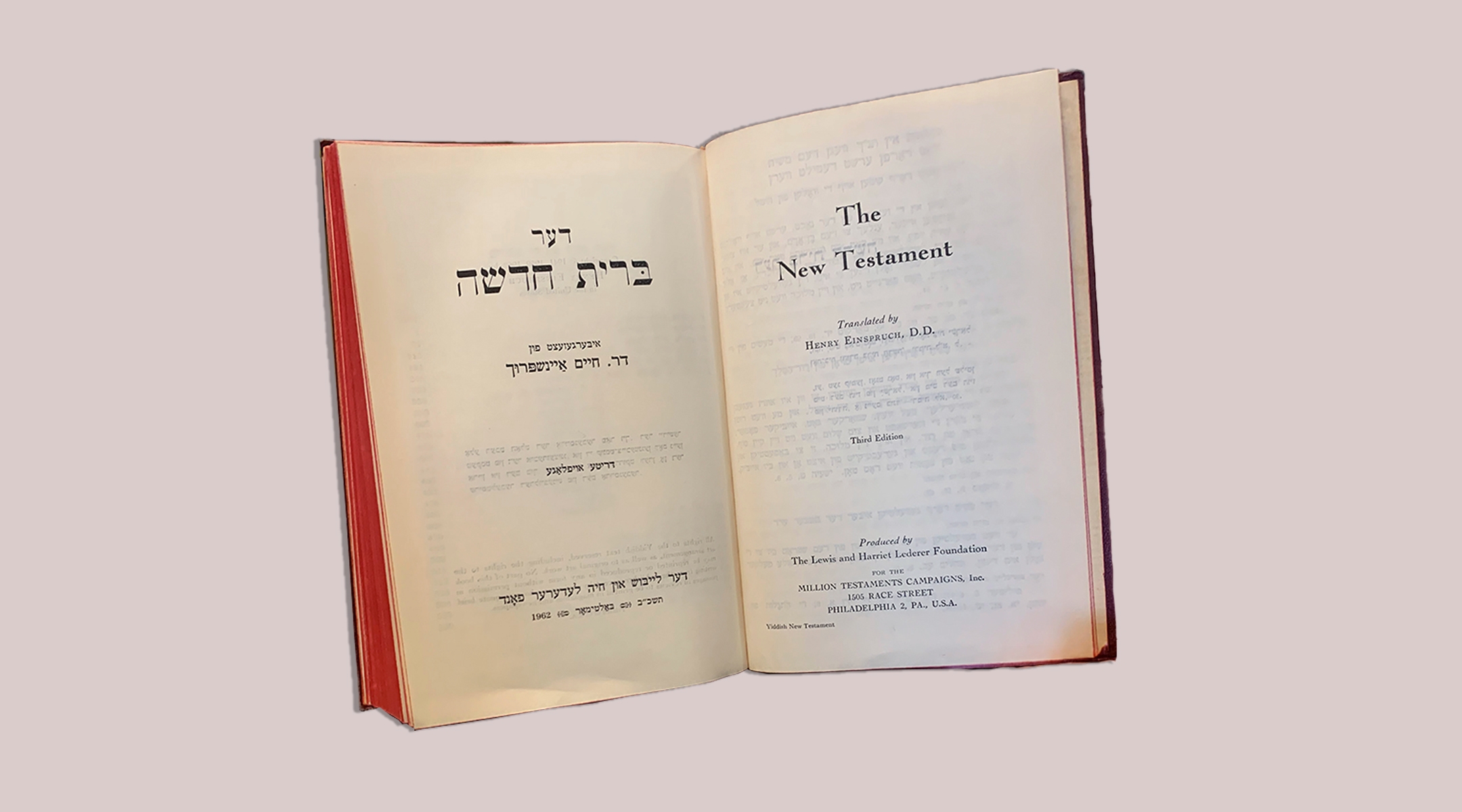

“The Gospel According to Chaim” is based on the life of missionary Chaim Einspruch, who was born into a Szanzer Hasidic family in Poland and “found” Christianity before immigrating to the United States in 1913. Einspruch eventually translated the New Testament into Yiddish and self-published it in 1941 after a Yiddish print shop turned down the job.

A production of the New Yiddish Rep, a New York-based theater company dedicated to Yiddish-language theater, “Gospel” is being billed as the first new, full-length Yiddish drama written in the United States in 70 years. According to David Mandelbaum, the company’s artistic director, the last original Yiddish drama in this country was written in the 1950s by famed Yiddish writer Leivick Halpern, author of the dramatic poem “The Golem.”

“The Gospel According to Chaim” is also the first full-length Yiddish play by Mikhl Yashinsky, a 33-year-old who has made a name for himself in New York as Yiddish writer, actor, teacher and translator.

Yashinsky stumbled upon Einspruch’s story in 2016 when he was a fellow at the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. Fellows are required to conduct tours of the center and, as such, Yashinsky become familiar with the Yiddish printing type Einspruch’s widow donated to the institution, which is on display in a recreated but non-functional Yiddish print shop. Some of Einspruch’s printing type will be used as props in the play.

“It got me thinking about the irony inherent in this singular individual,” Yashinsky told the New York Jewish Week. “He was a Christian who believed in the divinity of Jesus but was also a very proud Jew culturally. It made me want to look further into this person.”

Yashinsky wrote the first act of “Gospel” while he was in Amherst, naming one of the characters in the play Sadie after a colleague there. He completed the play in 2020 in Charleston, South Carolina, where he lived for a time during the pandemic before returning to New York more than a year ago.

Chaim Einspruch’s Yiddish translation of the New Testament. (Jon Kalish)

In the 1940s, Chaim “Henry” Einspruch drew the ire of Baltimore Jews by standing outside Orthodox synagogues and preaching about Christianity in Yiddish to Jews leaving Shabbat services. In addition to his translation of the New Testament, Einspruch also translated 100 Christian hymns into Yiddish in a collection titled “Hymns of Faith (Lider fun gloybn).”

Many Jews view efforts to encourage Jews to embrace Christianity as offensive and even antisemitic, with Jews for Jesus and other contemporary Messianic movements drawing particular scorn. But Yashinsky said he felt none of that as he sought to bring Einspruch to life.

“I wasn’t interested in just portraying him as a villain and having the play be a piece of propaganda against missionaries,” Yashinsky told the New York Jewish Week about his inspiration. “I really tried to understand why he was doing it. I don’t think Einspruch felt he was being malevolent in anything he did.”

Fascinatingly, Einspruch never formally converted to Christianity, “deeming his allegiance to evangelical Lutheranism a true fulfillment of his Judaism rather than apostasy or betrayal,” writes Naomi Seidman, a humanities professor at the University of Toronto whose scholarly article on translations of the New Testament into Yiddish was published in the Berkeley Journal of Religion and Theology. After Einspruch immigrated to the United States he earned a doctor of divinity degree at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. (Seidman will deliver a lecture on Thursday at YIVO, “A Very Jewish Christmas: When Jesus Spoke Yiddish,” discussing Einspruch’s New Testament translation, among others.)

“His native language was Yiddish and he enjoyed Yiddish literature,” Yashinsky said of Einspruch. “His innovation was writing this [New Testament translation] in a truly refined, literary, poetic, idiomatic Yiddish. It reads beautifully.”

Indeed, as Einspruch declares in one scene of the play — which takes place during Hanukkah and Christmas in 1940 and continues into 1941: “The holy Yiddish language is very precious to me.”

Yashinsky plays Einspruch in the production but that was not his original intent. A would-be actor who grew up as a Lubavitcher Hasid was in rehearsals to play Einspruch in a reading done last March but wasn’t up to the task, Yashinsky said. So the playwright decided to take the part himself. “The role felt good to me,” he said.

The other two characters in the play are Gabe, a printer Einspruch approaches to print the Yiddish New Testament, and Sadie, a friend of the printer and an anti-fascist activist alerting Jews to the atrocities happening in the Holocaust in Europe. During the course of the play, Sadie, whose father converted to Christianity, urges Gabe to turn down the New Testament job; Gabe, meanwhile, needs the business but is reflexively repulsed by the idea of Jews converting to Christianity.

The role of Gabe the printer will be shared by actors Sruli Rosenberg and Joshua Horowitz. Rosenberg, 30, grew up as a Satmar Hasid in Williamsburg and now lives in Monsey, a different Hasidic community upstate. He describes himself as “reformed hasidische” and said most of the time he doesn’t he doesn’t wear a kippah but he continues to observe Shabbat — meaning that Horowitz will play the printer then.

In an effort to master the English language, Rosenberg stopped reading and writing Yiddish as a teenager. He had little contact with the Yiddish arts revival until the Spring of 2021 when he attended Generation J, a Yiddish arts program in Germany, thinking he may want to become a writer. While he was there, Rosenberg was baffled when other participants informed him of the Yiddish theater scene in New York. “I’m, like, ‘No there isn’t. I would’ve known of it,’” he recalled.

Inspired, Rosenberg returned to New York and got a job as the assistant to New Yiddish Rep’s Mandelbaum, helping him move sets around the office and driving him around town. When Rosenberg was feeding lines to actors auditioning for “The Gospel According to Chaim,” Yashinsky asked him why he didn’t audition himself. Now, Rosenberg makes his professional acting debut in the play.

Sadie, a fiery antifacist organizer is played by Melissa Weisz, 40. In the play, on Christmas Day, she asks Einspruch: “And what are you going to give him as a gift, your messiah, huh? It’s his birthday, after all. Maybe a barrel of Jewish blood? A fitting gift. Maybe the extermination of another shtetl of Jews in Europe? His followers have been giving him such gifts for thousands of years, and it seems he never gets tired of it.”

Weisz, too, grew up as a Satmar Hasid in Borough Park and made her acting debut in 2010 playing Juliet in the feature film “Romeo and Juliet in Yiddish,” which set the Shakespearean tale in Hasidic Brooklyn. She also had one of the leads in a New Yiddish Rep production of “God of Vengeance,” the Sholem Asch play about lesbian love.

“These two characters come from very different places but they’re both trying to figure out how to save people,” she said of the link between protagonists Sadie and Chaim.

Yashinsky said he sees a wide audience for the show, despite its niche topic and language.

“Many will come who are attracted to Yiddish and to the various dramas and emotions and curious personalities that are part of its tumultuous 20th-century history,” he said. “But I hope anyone also comes who may have ever wondered about the entanglements of opposing religions, the holiday wars in America, the confluence of ethnicity and faith and identity and human ambition.”

The recent Yiddish-language version of “Fiddler on the Roof,” which had a revival last year after an initial run interrupted by the pandemic, introduced mainstream audiences to “supertitles” — English-language translations that are projected behind the actors. Supertitles will be used for “Gospel” but Yashinsky said even people who do not know Yiddish will benefit from hearing it on stage.

“The language should not hold anyone back,” he said. “On the contrary, I hope it draws them in.”

A bigger question is whether native Yiddish speakers in the city are likely to see the show. Rosenberg acknowledged that his Hasidic mother was not crazy about his career path. “Isn’t that the universal quarrel that parents have with their children going into the arts?” he said. “She definitely did not take well to it. She doesn’t get it. I don’t blame her.”

And new Yiddish Rep’s Mandelbaum chuckled when asked whether there might be chartered buses bringing theatergoers from Borough Park to see the play. But he does think that Yiddish plays can appeal to the Hasidic Orthodox community, as well as a more secular one: During the 2019 Folksbiene production of Leon Kobrin’s classic Yiddish comedy “Di Next-Door’ike (The Lady Next Door),” Mandelbaum said there were shows filled with young Hasidic Jews who had played hooky from their yeshivas.

Well aware of the Yiddish music revival that’s going strong in New York and abroad, Mandelbaum concedes that Yiddish theater has not enjoyed that same kind of renaissance.

“If Yiddish theater is to really have a life, then it is essential that there be people who are going to write Yiddish plays,” he said during a rehearsal break. “Yiddish theater ought to be more than re-staging things from the past. We need to have young Yiddish writers writing plays.”

Then he declared, “May there be many Yashinskys.”

“The Gospel According to Chaim (Di psure loyt khaim)” is performed in Yiddish with English supertitles. Previews begin on Thursday, Dec. 21; the world premiere is on Sunday Dec. 24 at 7:30 p.m. There will be a total of 21 performances through Sunday Jan. 7 at Theater for the New City (155 First Ave.).

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.