The writer Franz Kafka died 100 years ago on June 3, 1924, one month shy of his 41st birthday.

A century after his death, the books and stories by the Jewish writer from Prague remain widely read, and his cultural influence has been profound. And for reasons not entirely related to the anniversary, he is having a cultural moment.

Recent books include new translations by Ross Benjamin (“Diaries”) and Mark Harman (“Selected Stories”) and an anthology of short stories by celebrated writers, “A Cage Went in Search of a Bird: Ten Kafkaesque Stories.” ChaiFlicks, a Jewish streaming service, is airing a German-Austrian miniseries, “Kafka.” And Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries are currently mounting an exhibition, “Kafka: Making of an Icon,” about “how he continues to inspire new literary, theatrical and cinematic creations around the world.” One of those is mine: My novel about Kafka’s work comes out in October.

The Kafka revival has extended to a sphere that the writer could not have imagined: social media. See this recent Daily Mail headline: “Franz Kafka becomes an unlikely Heartthrob on TikTok — where Gen Zers are swooning over the Czech novelist nearly 100 years after his death.”

Not that Kafka has ever gone away. Kafka’s enigmatic writings, from the slim volumes he published during his lifetime to his great unfinished novels “The Trial” and “The Castle” to his voluminous letters, notebooks and diaries, have engendered a massive commentary spanning the last century. Interpretations of Kafka might have started among Central European Jewish intellectuals such as Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin, but in the decades following the Second World War Kafka’s reputation expanded well beyond this narrow group. Kafka had gone global.

Responses to Kafka’s work have varied widely. He has been recruited to support just about every intellectual, cultural and political trend one can imagine. Over the course of the previous century, critics have presented readers with many Kafkas. We’ve had the anti-bureaucratic Kafka, the anti-totalitarian Kafka, the psychoanalytic Kafka, the Gnostic Kafka, the socialist Kafka, the anarchist Kafka, the individualist Kafka, the Zionist Kafka, the anti-Zionist Kafka, the postmodern Kafka and many other Kafkas besides. If these were some of the Kafkas of the last 100 years, what might be the Kafka or Kafkas of the next century?

The answer is unknowable, but the first glimmers of future Kafkas are troubling — at least from my perspective, which is, admittedly, stuck back in the 1920s and 1930s. The most profound challenge facing Kafka’s work at the beginning of the second century after his death is the general and steep decline in the quality of reading.

People still read, of course, and judged by word count might read more today than ever before. But this isn’t serious reading. This reading is not only shallow by design, but it is also hostile to depth. The great enemies of the contemporary reader are ambiguity, inconclusiveness and confusion. Bewilderment, once the starting point for analysis (especially of Kafka), is now the endpoint of engagement in our entertainment-dominated culture. What follows the termination of our fragmented attention? A short online review and/or an adjudication of stars. One star, two stars, three stars — the codification of judgment. Reading has become rating.

At the time of writing this, Kafka’s “The Castle” has been rated 64,158 times on Goodreads. The novel’s score: 3.93 stars. “The Castle” holds a slight edge in average rating over “Spare,” Prince Harry’s memoir (3.86), though Harry’s book dominates Kafka’s masterpiece in total engagement with 369,882 individual ratings. Reading Kafka has become just another ancillary activity to support the vast online consumer economy.

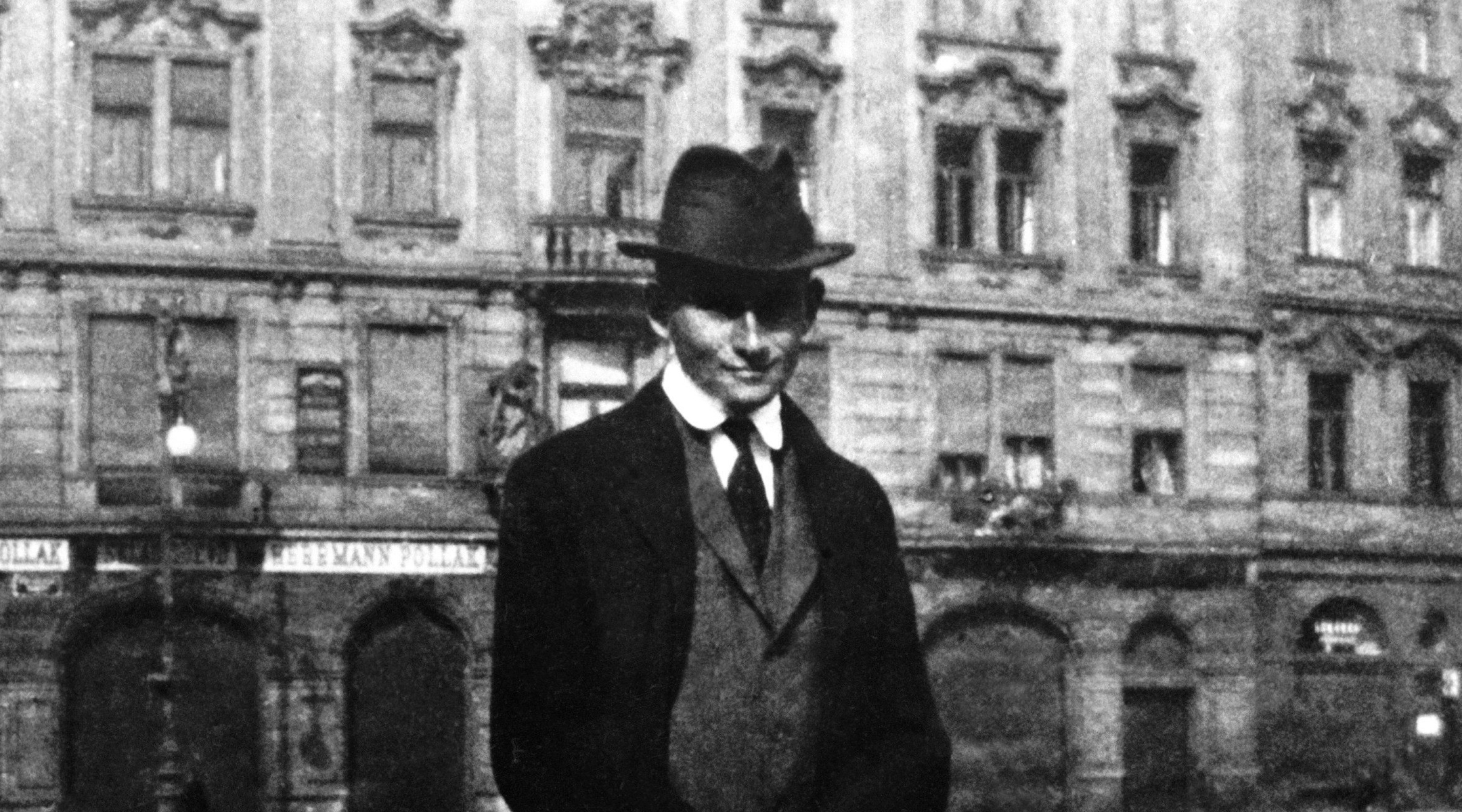

Franz Kafka stands in front of the Oppelt House on the Altstadter Ring in Prague, circa 1921, when he wrote “The Castle.” (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Reading today, however, is not only rating; reading is also posting and sharing. “Reading” in the social media sense is a component of (public and/or private) identity cultivation. In the social media realm, Kafka’s deeply ambiguous writings cannot exist, because if they were to exist, they would shatter the basic rule of social media communication: instantaneous meaning production and the elicitation of algorithmically predictable emotional responses — anger, fear, happiness, lust, etc. Kafka’s writings can do no such thing — and thus for “Kafka” to be absorbed by social media, he and his work must be reduced to the level of a meme.

Those who read Kafka’s letters and diaries know that he was a fully articulated social being, but across social media he becomes the quintessential loner and solitary genius. In our increasingly alienated culture, Kafka becomes an avatar of alienation. In our world of estrangement, Kafka is estrangement’s personification. Other Kafka-memes proliferate across social media: Kafka as brooding lover, Kafka as crisis of masculinity, and so on.

Kafka’s influence grew and his work endured precisely because of the work’s evasiveness and complexity. With Kafka, there is always another layer, another perspective, or a counter-perspective; there is always another possible meaning that collapses the previous interpretive certainty and forces the reader to start again, to start over, to rebuild.

Kafka was acutely aware of the unreliability of language as a medium of communication. Language resisted the writer; it refused to succumb to order and logic; it evaded meaning, slipped away from the writer’s intent. In a letter to his close friend Max Brod from 1910, years before he’d create the works that would make him famous to posterity, he wrote, “My whole body warns me against every word; every word, before it lets me write it down, looks first around in all directions. The sentences literally crumble before me.”

For Kafka, writing remained a struggle, even after he’d completed stories that are now known throughout the world — “The Judgment,” “The Metamorphosis,” “In the Penal Colony,” “A Hunger Artist” — after he started and abandoned novels that would help define the intellectual culture of the first half of the 20th century. For Kafka, it was a battle to move beyond the merely provisional or approximate. Such a battle was doomed — and yet still he waged it day after day until his last labored, dying breath.

There is still no escape for Kafka. He will become, as all else in today’s increasingly vacuous culture, merely a figure for memes — and this despite having produced the most meme-resistant body of work imaginable. The struggle against reductive analysis of his texts (and texts in general) cannot possibly withstand the flattening and emptying forces of social media. Sure, there will be the occasional throwback, those misanthropic defenders of a lost age (I count myself among them), whose sensibilities for whatever reason remain anchored to an antiquated modernism. They (we) wage a hopeless fight against the great surge of culture.

However insecure we might be, however conflicted we feel, we believe we are defending something important. Others, and especially those of the younger generations, think we’re foolish. We are, after all, detached from the economy of likes, shares, reposts, and ratings — that is to say, we are detached from the economy as such. We are attached to the non-quantifiable in what is becoming a totally quantified society.

In his biography of Kafka, Max Brod records a conversation he had with Kafka on Feb. 28, 1920. According to Brod, Kafka quipped that humans were but one of God’s bad moods, God having a bad day. When Brod inquired about the metaphysical hopelessness of this position, Kafka responded, “Plenty of hope, for God — no end of hope — only not for us.” The same might be said for literature today — infinite hope for Literature, no hope for our literary culture.

But maybe there is some hope after all. I propose what might seem like a radical experiment. Put away your phone. Forget about social media. Ignore reviews. Blot out those hundreds of thousands of stars that permanently illuminate even the darkest corners of our culture. Pick up a book by Kafka. Whatever you do, avoid the allure of posting an image of what you’re reading. Don’t post a photo of yourself reading the book — in other words, no selfies. Absolutely don’t share a picture of the artisanal pastry and fancy coffee drink that accompany your reading. It is not a performance. There is no audience.

Now read. Read deeply. Read freely. Think freely. Be absorbed in the text. Discover Kafka on your own. Only through you can Kafka live again.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.