This article is part of a series examining how Oct. 7 and its aftermath have changed the Jewish world. You can see the complete project here.

While she was studying last year at Columbia University’s journalism school, Eleanor Reich would walk by protests calling for her country to be destroyed. When she would pass by classmates in the hallways, she said, some would avoid her gaze.

Only when she returned home to Tel Aviv did she feel like she could exhale. She said when she arrived for her first trip back in December, she immediately started crying.

“At least here, even if I disagree with someone, at least it’s out of a shared narrative of this country should exist,” Reich, 27, said of her time in Israel. “In New York, when you argue with someone, you don’t know if they even think that my country should exist.”

She added, “I think that what really Oct. 7 did to me and a lot of people I spoke to was that it clarified for us that no matter where we are in the world, we’re first and foremost Israelis.”

Officially, about 200,000 Israelis live in the United States. But Israeli advocacy groups, taking a wider view than the U.S. Census, puts the number as high as 1 million. Some of the expats are here for temporary stints, others to build a permanent life far from their place of birth. But those who spoke with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency said that, since Oct. 7, despite being an ocean away, they feel much more Israeli.

“I’ve been living here for 23 years, and I discovered I’m much more Israeli than I thought,” said Vered Guttman, a chef and food writer who lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland and has done work on behalf of families of Israeli hostages this year. Since Oct. 7, she said, she has been watching Israeli TV news “every single hour of the day that I was awake,” something she had never done before.

“I cannot think of anything but the hostages and Israel, the feeling that my country is falling apart,” said Guttman, 56. “The United States is my country too, but Israel is still my country, and it feels like it’s really falling apart. I don’t know if it will survive this.”

Vered Guttman, left, and Eleanor Reich participating in political activism surrounding the Israel-Hamas war. (Courtesy)

Assiduously following Israeli news has been a common coping mechanism. Rabbi Amitai Fraiman, a Jerusalem native who moved to the United States 11 years ago, pointed to the news in explaining that the past year can be summed up as “a perpetual state of emotional jet lag.”

“Even just the simple fact of the news cycle, of when we get our news from Israel directly, that creates a delay in terms of our consciousness,” said Fraiman, 37, who lives in Palo Alto, California and runs a Zionist think tank. “There’s a certain time of day where there’s no news from there, so what are we supposed to be doing?”

For Boaz Atzili, a political scientist and a professor at American University in Washington, D.C., the daily hostage updates began from the moment he woke up on Oct. 7. Several members of Atzili’s family live in communities on the Gaza border.

“When you see hundreds of WhatsApp messages, when you wake up and you see, I have the alert system from Israel that also shows hundreds of thousands of alerts at the same time, you know that something is wrong,” Atzili said.

Atzili, 57, spent that day — and every day since — in constant communication with his family members in Israel. His 79-year-old aunt hid for 10 hours as Hamas fighters searched her home but did not find her, Atzili said. He would soon learn that two relatives — his cousin Aviv and Aviv’s wife, Liat, who lived on Kibbutz Nir Oz, were missing. Liat, who is an American citizen, was released in November as part of Israel’s weeklong cease-fire with Hamas.

One day after Liat was freed, the Atzilis learned that Aviv, who had been a member of Nir Oz’s emergency response team, had been killed on Oct. 7. Hamas still has his body.

For Boaz Atzili, the deeply personal nature of the war has helped put things in perspective. While he acknowledges the rise of antisemitism in the United States, especially on college campuses like his, he said those issues don’t compare to the hardship in Israel.

“I find it’s always a little bit hard to kind of relate to the fear of antisemitism and all that,” Atzili said. “I understand it and it’s real. But I also, all the time, [have] a feeling that, guys, that’s not the main story here. That’s a side story that is not nearly as threatening, as horrible, as what’s going on in the Middle East.”

A December 2023 dinner at Vered Guttman’s home. Guttman is seated on the far right. Yaniv Yaakov, whose brother Yair was killed by Hamas, is seated in the middle of the right side, across from Maryland Rep. Jamie Raskin, who is Jewish. (Courtesy of Guttman)

Elan Carr, the CEO of the Israeli American Council, which provides programming for Israelis living in the United States and advocates for the country politically, said rising antisemitism has affected Israelis here. By the end of the past school year, he said, IAC had directly responded to more than 600 reported cases of antisemitism in both public K-12 schools and on college campuses — more than the group had ever addressed before.

“When I say handled, I don’t mean made a statement,” Carr said. “I mean handled, caseworked, met with families, trained teachers and students, accompanied parents and families to school board meetings.”

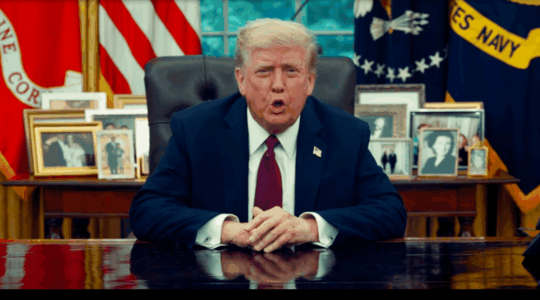

The IAC has also held trainings for 2,000 public school teachers across the country on “the IHRA definition [of antisemitism], on anti-Zionism, on Jewish peoplehood, on how to recognize antisemitism,” Carr said. The group also held a national conference in Washington, D.C., earlier this month headlined by former President Donald Trump, in whose administration Carr served.

Israelis have also been the driving force behind protests on behalf of the hostages in cities across the United States, where they have found community with each other. In addition to attending demonstrations, Atzili has written letters and met with politicians and Jewish community leaders to push for a hostage deal and a cease-fire. Guttman has been at some of the same protests.

Boaz Atzili meeting with Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff in September 2024 and with Rep. Nancy Pelosi in July 2024. (Courtesy of Atzili)

“I think that many of us Israelis here felt the need to do something when we were just going crazy from day one,” Guttman said.

Some Israelis said they have paid a social price for their national identity. One 38-year-old tech worker from Brooklyn said she has lost several friends over fallout from the Israel-Hamas war. She defined the past year as “a combination of grief, anger and a sense of betrayal,” particularly from the “Brooklyn liberal left” with which she identifies.

“I feel like in the circles I run in, or used to run in, what has been a leading value was always acceptance, hearing everybody, respecting everybody, understanding complexity, intersectionality, holding different narratives in the same way,” she said. “And post-Oct. 7, all of that seemed to crumble down. Now there’s a sense that those circles found the true evil, and that true evil is Israel, and what Israel is doing, and all of the values that I felt they held before were kind of abandoned.”

The Brooklynite tech worker, who moved to the United States 12 years ago, declined to share her name, explaining that she “felt a deep rift in what I believed was my identity, who I can be comfortable and authentic around, and which parts of myself I can safely share.”

Like Reich, she said she felt most comfortable when visiting Israel.

“Because of who I am, my circles in Israel are also the liberal left,” she said. “So I felt like I could finally have the complex conversation of, ‘We disagree wholeheartedly with the government, we believe the war needs to end, what’s happening in Gaza is terrible. Having that said, Oct. 7 happened, that was also terrible, Israel has the right to exist. Israel has the right to defend itself,’ which I feel like is a narrative that doesn’t exist in the U.S.”

For some, that feeling of belonging in Israel has prompted a question: When do we move back?

Fraiman, the Palo Alto rabbi, visited Israel in July for his brother’s wedding. He said the “urge” to move back to Israel has only intensified since the war began.

“Like most Israelis, the joke is that we’re on our 11th year of our three-year plan,” Fraiman said. “When we first came it was never the intention to move or relocate in this way. It’s just, life happens, and so the conversation of coming back is always alive and well with me and my wife.”

The Brooklyn tech worker said moving back to Israel was always part of her plan, but larger forces got in the way, from COVID to economic downturns to the upheaval over judicial reform in Israel to the war.

“Suddenly it became like, what am I doing here?” she said. “But also, I have two small children that I need to think about their future, and right now, the reality in Israel is very gloomy. So getting on a plane sounds irresponsible.”

While the past 11 months have brought considerable pain and anguish for many Israeli-Americans, there have been silver linings. Guttman, for example, said she and her husband felt an outpouring of support from neighbors they didn’t previously know.

“We suddenly had neighbors who were never in our house — we didn’t even know they knew we were Israelis — come and knock on our door just to say how sorry they were for everything that was going on and thinking of us,” Guttman said. “We personally only got the most supportive, thoughtful reaction from people and neighbors.”

Miriam Buium, an Ashdod native who moved to San Diego in 1999, said she and her husband have felt a similar embrace. In fact, Buium, 49, said it is her interactions with others — especially non-Israelis — that give her hope for her native country.

“We have friends over here that are Muslims, and we work with them, and we go to their restaurants, and with the majority of them, the 90% of them, we have no issues,” Buium said. “So in the future, I do believe, if we can live here together, we can live together in Israel.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.