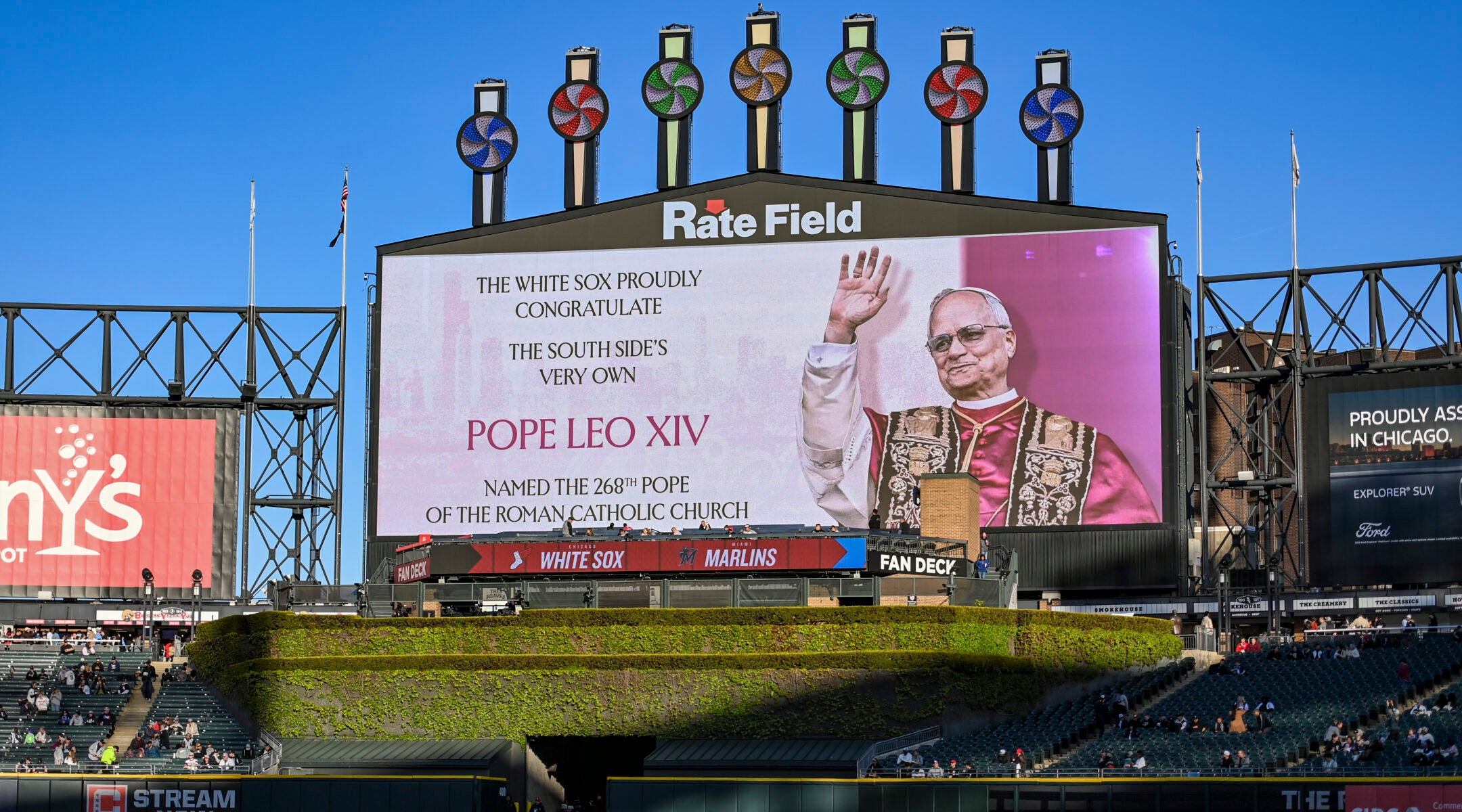

As a Chicagoan who teaches at Villanova University, it was surreal for me to watch the election of Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost as Pope Leo XIV last Thursday. The new pontiff grew up in Chicago and graduated from Villanova, a Catholic school, in 1977. Amid general excitement over the first U.S.-born pope, my networks also erupted with Chicago and Villanova pride.

Yet as much as I loved the memes about deep dish pizza and basketball, I noticed that the most important part of my identity was absent from the pope’s profile: He didn’t seem to have a record on Jewish issues or any meaningful relationships with Jews. Jewish journalists searched for signs of what his election might mean for Jewish-Catholic relations. Little turned up.

The contrast with Leo’s predecessor is striking. Pope Francis collaborated closely with Argentine Jews during his years as a cardinal. When he was elected in 2013, some commentators charted possible directions for Jewish-Catholic dialogue. Leo’s record offers no such clarity.

However, Francis also shows that a pope’s personal connections with Jews are no perfect predictor. By the time he died last month, Jewish-Catholic dialogue was at its most tense since World War II due to what many Jews (and some Catholics) perceived as his lack of sympathy for Israel in its war against Hamas. One leading Catholic journalist even identified the “crisis” in Jewish-Catholic relations as the most underreported Vatican story of 2024.

It wasn’t just about Israel, though. Long before the war, Francis repeatedly echoed “old-fashioned” Christian anti-Judaism. This included disparaging comments about Jesus’s Jewish contemporaries and the Torah. By the time he cited the single most anti-Jewish New Testament verse on the first anniversary of the October 7 attack, the pattern was clear.

Tracking a new pope’s personal relationships with Jews only gets you so far. Their local context is just as important. Like all people, popes are products of their local context. Yet unlike all people, popes elevate that context to a global stage, bringing it to bear on the whole church — including its stance toward Jews.

To fully understand why Leo’s context matters, we need to compare it to his predecessor’s. The Argentine Francis was the first pope from what is often called the Global South: countries in South/Central America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia that have been marginalized and exploited by Eurocentrism. This is where Catholicism is growing most rapidly. Francis’s work confronting poverty, violence, and colonialism in Latin America directly shaped his global purview and focus on social justice. These characteristics endeared him to U.S. Jews, who have little interest in church doctrine but skew politically liberal.

At the same time, Francis’s local context had complicated consequences for his approach to Jewish-Catholic relations. For one, there simply aren’t many Jews in the Global South. The Jewish population of Argentina is actually the region’s largest, but it’s small both percentage-wise and compared to other Jewish centers. In Francis’s world, the Jews that Catholics encounter most frequently are the villains in the New Testament. This surely impacted his religious education, perhaps explaining his habit of unreflectively invoking Christian anti-Judaism.

Moreover, Francis was the first postwar pope without direct connections to the Holocaust. This matters because the Holocaust has been the main motivator for Jewish-Catholic reconciliation, especially as reflected in the reforms of Vatican II. While Francis obviously deplored the Holocaust, he saw it as enjoining the church with a universal commitment to humanity rather than a special commitment to Jews. This is different from how European Catholics often see things. Tellingly, some of the harshest Catholic critics of Francis’s Israel statements were German.

Drawing on his local context, Pope Francis called for a church committed to justice for marginalized groups. U.S. Jews rightly admired this vision. Yet due to the very same context, Francis also didn’t intuitively count Jews among those marginalized groups—even though there has arguably been no single group more historically marginalized (to put it mildly) by the Catholic Church itself. In this way, Francis embodied an inconvenient truth: because progress in Jewish-Catholic relations has been so intertwined with the European experience, future progress is uncertain as the Catholic Church becomes less Eurocentric.

This is where Pope Leo XIV comes in.

Leo spent most of his pre-Vatican career in Peru, where he confronted the same issues that Francis did. As a naturalized Peruvian citizen, he’s been called the second Latin American pope in addition to the first U.S. one. There’s every reason to believe that he’ll continue his predecessor’s progressive focus on poverty, immigration justice, and climate change.

But this doesn’t mean that we should brace for similar Jewish-Catholic tensions. Although Leo left the United States, he did still grow up here. In contrast to Francis’s context, the United States is perhaps the most flourishing Jewish diaspora in history. There are, in fact, almost twice as many Jews in Chicago alone as in all of Argentina. While they constitute a small percentage of the overall U.S. population, they play an outsized cultural role. Moreover, although the Holocaust doesn’t implicate U.S. Catholics in the same way as European ones, it casts a long shadow because World War II is so central to U.S. national identity.

These realities matter. Although U.S. Catholics are politically and culturally divided, they consistently report high opinions of Jews. This includes affirming Jews’ covenant with God, denying that the Jews killed Jesus, rejecting proselytization, and sympathizing with the state of Israel.

Institutionally, the U.S. church prioritizes Jewish-Catholic relations. Most Catholic universities support Jewish studies and/or Jewish student groups. Many — including the Chicago seminary where Leo studied — have centers for Jewish-Catholic dialogue. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops even declares that the church’s “unique relationship with the Jewish people is grounded in a shared heritage, making it unlike any other dialogue with another religious tradition.”

This doesn’t mean anything definitive about Pope Leo’s own views. But my point is that his views aren’t the whole picture. Whether he wants to or not, he’s bringing U.S. Catholicism with him to Rome in an unprecedented way. A local Catholic culture with rich Jewish-Catholic engagement is gaining a global profile. Catholics with deep commitments to Jews have a new platform.

To be clear, U.S. Jews hoping for a sudden pro-Israel shift in the Vatican will almost certainly be disappointed. The new pontiff resumed his predecessor’s calls for a ceasefire in his first Sunday address. Official church policy on Israel or the war is unlikely to change.

What I do think U.S. Jews may reasonably hope for, however, is improvement in the general climate of Jewish-Catholic relations. Many U.S. Jews strongly identified with Francis’s progressive agenda but felt burned by his insensitivity to Jewish concerns and experiences. If any pope could give Jews the best of both worlds, it would be one who grew up in the United States but developed his pastoral commitments in the most underprivileged countries on earth.

That is exactly who the conclave elected in Pope Leo XIV.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.