Following the fatal shooting last week of two employees of the Israeli embassy outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington D.C. on May 21, Rabbi Noam Marans of the American Jewish Committee offered a prayer.

“Our modern American Jewish chronicle of pain has a new locus: Pittsburgh, Poway, Monsey, Jersey City, and now Washington,” it read in part. “And innumerable antisemitic attacks, too many to list, in Brooklyn, on campuses, and beyond.”

The next day, The Guardian, the left-leaning British paper, linked the murders of Sarah Milgrim and Yaron Lischinsky to a different set of violent attacks.

“This is the latest act of violence in a string of incidents that have affected Jewish, Arab and Muslim communities in the US,” read its report. “A man in Illinois attacked a six-year-old and his mother, both Palestinian American, and killed the boy in 2023 soon after Hamas’s 7 October attack on Israel, and three Palestinian students were shot in Vermont in November 2023. Reports of antisemitism, Islamophobia and anti-Palestinian racism have soared since the war began.”

The difference between the two litanies is wide and telling. For Marans, whose organization hosted the “young diplomats” reception that the murdered couple attended on the night of the shooting, the attack was the latest in a series of incidents, unrelated to the conflict in Israel, that left American Jews dead or wounded in synagogues, a rabbi’s home and a kosher supermarket. For the Guardian, it was a political shooting, a sort of globalization of the conflict in Israel and Gaza.

Attempts to characterize the murder of Milgrim and Lichinsky may be premature: We haven’t learned how the shooter, who chanted “Free Palestine” while being arrested, identified his victims, or whether he knew they were embassy employees.

But in the absence of clarity there is anger and certainty. Some Jews have bristled at news outlets that lean hard into the couple’s Israeli affiliation, as if suggesting that the shooting, however heinous, was strictly political. A recent Associated Press headline becomes Exhibit A: “Court papers say suspect in embassy killings declared, ‘I did it for Palestine, I did it for Gaza.” The shorthand “embassy killings” falsely implies that the shooting took place at the Israeli Embassy and not at an American Jewish institution.

“I was really upset when I saw the news and all the mainstream news channels said, ‘Two Israeli Embassy staffers shot and killed,’ instead of, ‘Two young people murdered in an antisemitic attack, coming out of a Jewish event in a Jewish museum in Washington, D.C.,” Sharon Brous, the rabbi of the independent IKAR community Los Angeles,” told The New Yorker. “This person was looking for Jews to kill.”

In the week since the shooting, two distinct framings of the murders have emerged, sometimes overlapping, often not.

In a Truth Social message, President Donald Trump wrote that the killings were “based obviously on antisemitism” — an assertion echoed in a news release from the Justice Department announcing the shooter’s arrest.

While Elias Rodriguez was charged with “the murder of foreign officials” and not a hate crime, Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division Harmeet Dhillon said in the statement: “Let me be clear: hateful violence against Jewish Americans will be met with the full force of the Justice Department.”

“Make no mistake: This attack was targeted, antisemitic violence,” Assistant Director in Charge Steven J. Jensen said in the same statement.

On both ends of the Jewish political spectrum, leaders are saying it is important not to deny the fears of Jews or somehow “excuse” an act that could have happened anywhere where Jews gathered.

“I know there are some people who say maybe it wasn’t anti-Semitic, it was political. No. It was 100% an anti-Semitic crime,” wrote Rabbi Jill Jacobs, of the progressive rabbis group T’ruah, shortly after the attack. “There’s no equivocating about that. It was an attack outside of a Jewish museum, outside of a Jewish event.”

The suspect, meanwhile, told detectives that he admired Aaron Bushnell, the former U.S. airman who set himself on fire last year outside the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., where he shouted “Free Palestine!” in protest of the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza.

This has bolstered those who believe that Rodriguez was acting out of political, not antisemitic, motivations. Even as they denounced the murders and sometimes concluded the killings were antisemitic in effect, they seemed eager to maintain the distinctions between antisemitism, or hatred of the Jews, and anti-Zionism, a disavowal of Israel and the idea of a Jewish state.

“Their murders were undoubtedly political,” Zack Beauchamp, who is Jewish, wrote in Vox. “In video of the perpetrator’s arrest, he yells ‘free Palestine’ — a slogan that eyewitnesses also heard him repeat after the killing. A manifesto, published on X under the shooter’s name, lays out a clear motivation: punishing those he saw as complicit in Israel’s mass killing of the Palestinians.”

Eliding that debate over antisemitism, The Guardian put the D.C. killings in the context of rising “antisemitism, Islamophobia and anti-Palestinian racism” since the start of the war, as well as what one scholar tells the reporter is an “era of violent populism,” which has included assassination attempts on Donald Trump and threats of violence against judges and government officials.

For many Jews, however, such arguments deny the specific insecurity Jews have faced in the face of hatred for millennia — and that can be redoubled when sometimes violent rhetoric is directed at Israel and its supporters, or holds them “complicit” for the war in Gaza.

In an oped he wrote for Time, Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, omits the detail that Lischinsky and Milgrim, whom he refers to as a “young couple,” were embassy employees, as if to deny oxygen to those who might classify the murders as “political.”

Sarah Milgrim and Yaron Lischinsky seen at an Israeli Embassy event to mark Israel’s 77th Independence Day on May 10. (X)

“This wasn’t random violence. This was targeted antisemitism,” wrote Greenblatt. “This was an attack, not just against the D.C. Jewish community, but against all Jewish Americans — and indeed all Americans. What is so infuriating and sad is that, in many ways, it was only a matter of time that a murderous incident such as this would happen.”

Like a few other commentators, Greenblatt linked the murders to the recent Passover firebombing at the official residence of Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro by a suspect who said he held the Jewish politician responsible for the deaths of Palestinians. That attack also led to a debate over labels. While many Jewish leaders insisted such attacks are inevitable following months of heated anti-Israel rhetoric that often conflates Jews and Israelis, Shapiro himself appeared reluctant to call it an act of unambiguous antisemitism.

Debates over semantics are complicated by the often impassioned relationship between American Jews and Israel. Support for the country has been a cornerstone of most American synagogues and its most important Jewish institutions for 50 years and more. Some campus protesters say it is fair game to protest outside a Hillel building, which in addition to religious services hosts celebrations of Israel.

As the Forward noted in a story after the shooting, the AJC itself is “a staunchly Zionist organization that has placed support for Israel at the center of its lobbying agenda in the U.S. and abroad for decades.”

Indeed, in his statement about the murders, AJC’s CEO, Ted Deutch, said that “it strongly appears that this was an attack motivated by hate against the Jewish people and the Jewish state” — acknowledging that the two hatreds are not mutually exclusive.

And yet Jewish students on campuses and Jewish leaders at Zionist organizations note how heated rhetoric about “Zionists” too often conflates the actions of the Israeli government with a familial connection that most American Jews hold for a country where more than half of their fellow Jews live. While often that connection is political, Israel’s harshest critics often demonize Jews who don’t disavow Zionism — essentially the American Jewish majority.

In an interview with Time, Jacobs emphasized the blurring of anti-Zionism and antisemitism. “In the broader context, anti-Semitism has risen over the last couple of years and some of it has emerged from anger about the war,” she said. “And certainly anger about the war and the way Israel has carried out the war is justified, but that should not translate into anger or violence against Jews.”

John Podhoretz, writing in the conservative Jewish magazine Commentary, acknowledged that the museum shooting was a “different kind of event” than the attacks on synagogues in Pittsburgh and Poway, California, in 2018 and 2019, but only because the latter were carried out by white supremacists. But he too warned about turning their murder into a mere “political” killing. “It happened at a secular Jewish site, and targeted an event sponsored by the American Jewish Committee for young diplomats. And it was self-evidently an act of anti-Semitic terror in the nation’s capital,” he wrote.

A better comparison, Podhoretz wrote, was to the 2015 attack on the Hypercacher supermarket in Paris, when radical Islamists shot and killed four Jews at a kosher supermarket.

The stakes in such comparisons and distinctions are more than semantic. Many Jewish leaders and observers say that the often violent rhetoric of the pro-Palestinian movement imperils Jews no matter where they live, or where they stand on Israel.

“For a year and a half, some within the pro-Palestine movement have signaled that the way to put political pressure on Israel is not merely to protest in front of Israeli Consulates and Embassies,” Naftali Shavelson, former media director at the Consulate General of Israel in New York, wrote in the New York Times. “Rather, it is to intimidate Jewish families going to Sabbath prayers and Jewish students going to get-togethers on campus. It has, in many instances, turned debate over the Israel-Hamas war into a pretext to denigrate Jews.”

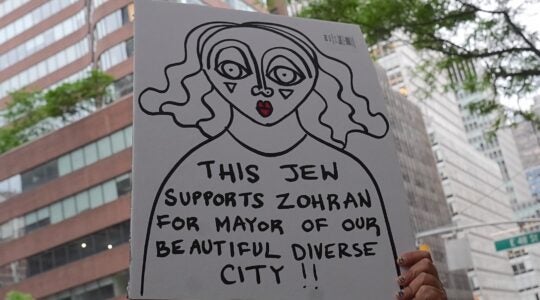

Some accuse Israel’s supporters of invoking antisemitism to quash support for Palestinians and criticism of Israel.

“It’s despicable, and nothing short of journalistic malpractice, that the media class is scrambling to reframe the shooting that targeted two Israeli state officials as a random antisemitic attack, even though it was undeniably, and by the alleged shooter’s own admission, a response to the ongoing Israeli assault on Gaza,” the Palestinian activist Mohammed El-Kurd, who writes for The Nation and Mondoweiss, wrote on X.

Writing in The New Yorker, staff writer Emma Green offered a framing for the murders that acknowledged the facts arrayed by both sides, but validated those who see the crime as the latest in a string of horrors extending from Pittsburgh to Poway to the streets of the nation’s capital.

“Rodriguez spoke in the language of anti-Zionism, but he acted with the logic of antisemitism, which has as its foundational myth that all Jews are collectively to blame for the policies of the Israeli government and, often enough, for the ills of the world,” wrote Green. “Rodriguez allegedly found two people, whose lives he knew nothing about, and made them die for Israel’s sins.”

On Thursday, a week after the shooting, Jacobs returned to its aftermath in an extended essay she posted on Facebook. She likened pro-Palestinian voices that have declined to condemn the D.C. murders as antisemitic or painted them as a justified political act to pro-Israel voices that have dismissed evidence of suffering in Gaza, including the deaths reported this week of nine children in a single family.

“Too much of the discourse around this horrific war, perhaps especially in this past week, has been like that of sports fans who are fiercely loyal to their own team and refuse to concede any merit to the other,” Jacobs said. “Some are more concerned with scoring points for their own side than with the actual human tragedy. But this isn’t sports — it’s human beings.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.