As a Jewish woman, public health professional and advocate, New Yorker and mother, I feel the fear coursing through our community. Antisemitic violence is rising, and Jews across the country increasingly report feeling unsafe. A survey by the American Jewish Committee found that nearly half of American Jews feel less secure today than just a year ago.

At the same time, political violence is escalating. On Wednesday, conservative activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated while hosting a campus event — the latest killing in a troubling rise in shootings targeting people across the political spectrum. In May, two Jewish professionals were gunned down leaving an event at the Jewish Capitol Museum in Washington, D.C. And in August, the shooter in the Minneapolis school mass shooting had scrawled antisemitic writings across the assault weapon — a chilling reminder of how deeply intertwined gun violence and hate have become in America.

Regardless of motive, these tragedies reveal the same truth: when dangerous rhetoric collides with easy access to guns, violence follows. More guns will not make us safer — they will only perpetuate this cycle.

My own path into this work began in the Jewish community after the Sandy Hook elementary school mass shooting in 2012. I joined my synagogue’s social justice committee, which mobilized to advocate for safe storage laws in New York. That preventable tragedy also struck close to home: a colleague at my law firm had a young son who survived the Sandy Hook shooting. The horror of that day rocked their family, our community, and the entire nation — and propelled me to deepen my advocacy. I went on to lead my synagogue committee, serve on a gun violence prevention committee at the JCRC, and ultimately shift my career from law to advocacy. Today, I serve as executive director of New Yorkers Against Gun Violence. For me, Jewish identity and the fight to end gun violence have always been deeply connected.

Understandably, Jews (and many others) may feel afraid and powerless during these tumultuous and divisive times. History teaches us that in periods of crisis and conflict, fear drives people to seek control and protection. But firearms add volatility to already stressful situations — domestic, civil, and personal. Jewish Americans have long recognized this: In 2018, 70% said it was more important to control gun ownership than to broaden gun rights, according to the American Jewish Committee’s Survey of American Jewish Opinion. In 2022, the Jewish Electorate Institute found that 77% of Jewish voters believe gun laws are not restrictive enough — a clear recognition that fewer guns, not more, will make our communities safer.

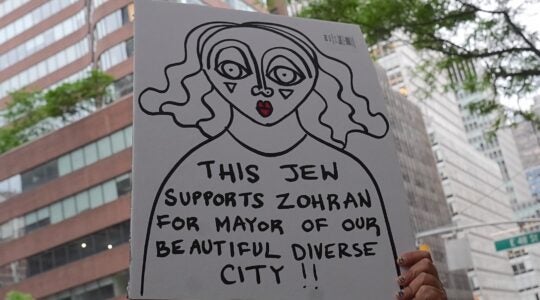

So I am deeply concerned by recent calls for Jews to arm themselves, and signs including this week’s new report from a Jewish security group urging limits on gun-carrying in synagogues that some Jews may be heeding the calls. Safety should be an assumption, not something we buy with weapons that put our families at even greater risk.

This spring, I spoke at a summit on domestic violence in the Jewish community convened by UJA-Federation of New York. Guns came up again and again — not as protection, but as instruments of control and intimidation. Women shared how ads for firearms were appearing more frequently in their social media feeds and even in print publications, as if the gun industry were deliberately targeting Jews at a moment of heightened vulnerability. In conversations over the course of the summit, many confided that neighbors and relatives were purchasing firearms “for safety,” though in reality those families were now at greater risk. As Alex Roth-Kahn, UJA’s managing director of caring, noted at the summit, a trend toward gun ownership in homes where safety is the concern is alarming — and dangerous.

The evidence is clear: Guns don’t make us safer. They make us more vulnerable. A firearm in the home doubles the risk of homicide and triples the risk of suicide. For women in abusive relationships, access to a gun makes them five times more likely to be killed. Guns purchased for self-defense are far more likely to be used in suicide, domestic violence, or accidents than in protection.

That’s where we must invest today. Strong gun laws save lives — from keeping firearms away from people with records of violence, to requiring safe storage at home, to prohibiting guns in sensitive places like college campuses and protests. New York’s laws are strong, but we have so much more work to do at the state and national levels.

And beyond laws, we must strengthen the supports that truly keep families safe. As Roth-Kahn emphasized, that means expanding access to mental health support, domestic violence services, and crisis prevention programs, while also investing in education, bridge-building, and conflict resolution with the broader community.

Whether the violence stems from hate speech, political extremism or personal crisis, the common denominator is almost always the same: easy access to guns. Until we break that link, the cycle of violence will continue. Let’s choose a different path. Let’s protect our children, our neighbors, and ourselves by investing in life — not in more tools of violence.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.