I used to enjoy your articles,î says Lavi Greenspan, ìbut now that Iím blind I canít read them.î That and flying a rocket is all he canít do, and heís getting along just fine. Greenspan, 28, who lost his sight nearly 18 months ago after the ìsuccessfulî removal of a benign pituitary tumor destroyed his optic nerve, has since graduated Fordham Law, passed the bar, traveled to Israel by himself, and is about to graduate Yeshiva Universityís rabbinical school. On Shavuot, he stayed up for the traditional all-nighter at the Young Israel of Hillcrest, studying the Oral Torah with a friend, until the Queens sky turned from black to blue and morning prayer commenced.ìBlessed are You,î said Greenspan by heart, ìKing of the Universe, Who gives sight to the blind.îIn the past, he says, God gave him sight, allowed him to know the beauty of creation, the details and shading of a loved oneís face.

In the present, he says, God has given him the gift of a Jewish community that embraces him, honors him, helps him, utilizing the gift of their own sight to ìgive sightî to the blind.In the future, he believes God might inspire scientists to heal the mystery of a broken optic nerve, giving full blossom to that morning blessing and sight to the blind. He knows that it is not given to man to know the magnitude of Godís future grace, but somewhere there is the beauty of faith.Does the deprivation of sight mean a man must be deprived of a womanís love, or that his heart is incapable of loving? ìIíve had dates, though honestly, theyíre hard to come by,î he says. ìI canít fault anyone.

Though a blind man ìseesî a womanís face by tracing his fingers slowly over the contours of her cheekbones and lips, Greenspan says he is shomrei negiyah, observant of the Jewish laws of modesty that preclude premarital touching. ìMy rebbe gives me permission to hold on to a womanís elbow,î when they walk together, as he holds on to the elbows of men who lead him to the synagogue aisle to kiss the passing Torah. However, on a date, when his hand touches a sleeved elbow, ìI feel very uncomfortable and can only imagine what the girl is feeling … I believe that one day I will get married.îThere is an informal network of several blind religious Jewish men, who talk occasionally on the phone. At least three of them are married, with healthy children, and this possibility once seemed just as distant to them as it now does to the otherwise-healthy Greenspan.

Of course, Iím not happy being blind but I feel much closer to Hashem now. I really feel heís Avinu Sheh BaShamayim, our Father in Heaven. ìI say Tehillim every day, and at the end I address Him as Tati, Abba, FatherÖ please help me. I also feel closer to Him because of the greatness of the Jewish community. Everyone has been there for me.î When he was in the hospital, Satmar women, doctors with knitted yarmulkes, Jews he never knew, came by because he is, well, a Jew ó instant family. Nearly a dozen of Americaís greatest rabbinic sages gave Greenspan their phone numbers, even cell phone numbers, so he can call them every week or so, to talk Torah and work through spiritual issues.His religious neighbors came through with help for his secular studies, as well. When word got out that the newly blind man could use some assistance studying for the bar, ìwithin two days,î says Greenspan, ìmore than 30 lawyersî from the Young Israel of Hillcrest and other local shuls, ìvolunteered to come over and study with me.îHis brother, Nadav, a chef at Yeshiva University, drives him to the rabbinical program in Washington Heights. A friend escorts him home.Citizens, otherwise strangers to him, have helped, too. ìThis is a medinah shel chesed,î a country of kindness, says Greenspan. The Lighthouse group has assisted him, and the government passes laws that enable the disabled. There is tuition assistance and transportation assistance by the cityís Access-A-Ride program, and the city orders grooves in subway platforms to advise the blind of proximity to the edge. The telephone company doesnít charge for directory assistance. He pushes a button and the time is announced on a pager-like appliance. Heís learned from others how to arrange the $1, $10, $20 bills in his wallet, how to navigate a crosswalk, how to do all the little things that arenít little at all.

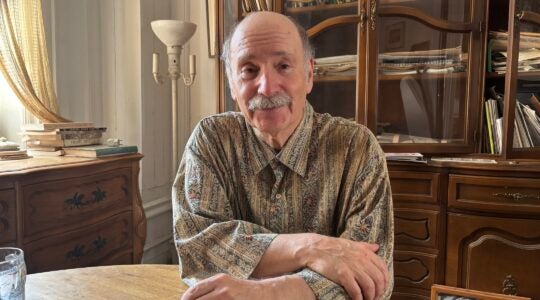

Stripped of his sight but not his dignity, he dresses in a suit and tie to greet a visitor. Courteous, and as evidence of his resourcefulness, he sets the table with coffee cake, a dish of pistachio nuts, a bowl of ice cubes, Coca-Cola, mandel bread. He lives with his parents but they arenít home to help. ìWould you like some juice?î he asks. ìA doughnut?î He moves around the living room and kitchen without a cane. He moves knowing that once on these walls he saw photographs of nieces and parents. Once, from these shelves, he took down holy books and histories, Judaica and newspapers.He wants to talk about The Jewish Week, the articles he remembers from before, the faces in columnistsí pictures: ìDo you still have a beard?î he asks. Even the most insignificant things that are seen in the land of sight suddenly resonate to a refugee in his near yet distant place.Light slipped away so fast; ìfrom August of 1997 through that Chanukah I was losing it. Iíll be honest, I was running from doctor to doctor,î anticipating a medical solution rather than thinking those were the last days of vision. ìEverything went so fast.îHe demonstrates that he is anything but needy, insisting his visitor take a brown-bag meal he prepares. In the brown bag is an apple, redder than lipstick, something to see.Light slips away and he whispers by heart the Maariv, a blind manís evening prayer: ìBlessed are You… who brings on the darkness.î

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.