The Israeli political landscape was rocked again this week with the surprise announcement from Ariel Sharon that he had reached a tentative agreement to bring the Likud Party of defeated Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu into the new coalition government.

Just last week, the leader of the ultra-Orthodox Shas party, Aryeh Deri, stunned the nation by giving up his post at the insistence of Prime Minister-elect Ehud Barak. Barak had demanded that Deri, who was convicted in April of corruption, step aside before Shas could discuss joining his coalition.

But those talks apparently reached an impasse over several Shas demands, including one that it remain in charge of the Interior Ministry. Barak’s chief negotiator, David Libai, said Barak viewed them as “ultimatums, meaning accept it or we quit. [Barak] did not accept any ultimatum.”

On the other hand, Sharon told Globes, an Israeli business publication: “In my opinion, a government can be formed in which the Likud will be a genuine partner and will be able to take part in the real decisions. All the problems between us can and should be quickly solved.”

Globes said Barak had offered Sharon the Ministry of Finance portfolio. Sharon previously had said he wanted only to continue serving as foreign minister, but that post apparently has been promised to Gesher Party leader David Levy, who held the position during the tenure of Prime Minister Shimon Peres. The other key portfolio, the Defense Ministry, Barak has said he will keep for himself.

Israel radio said Barak and Sharon had reached agreement on several key issues. Among them:

n A ministerial commission, to include Likud, would be formed to oversee peace talks with Syria, Lebanon and the Palestinians.

n Likud would drop its demand that none of the occupied Golan Heights be returned to Syria. Meanwhile, Barak would not agree to Syria’s demand that negotiations about the Golan resume where they were broken off by the Labor government of Shimon Peres in 1996. The agreement reportedly called for Israel to withdraw from the Golan in return for peace and security guarantees.

n Likud would receive five ministerial portfolios. It won 19 Knesset seats.

n A separate cabinet committee, with equal representation from the political left and right, would deal with the future of Jewish settlements and remaining differences between Likud and Labor.

Many observers welcomed the shift from Shas to Likud, viewing it as an easier fit with Barak and his One Israel bloc of the Labor, Gesher and Meimad parties that won 26 Knesset seats. Talks between Barak and Sharon, the interim leader of Likud, had occurred shortly after Barak’s landslide victory over Netanyahu May 17, but they quickly stalled.

“The shidduch [arranged marriage] between Likud and Labor is more natural [than Shas],” said Benny Elon, a Knesset member from the right-wing Unity Party founded by Benny Begin. “Likud represents the type of people Israelis want. Israelis want to have me and the real left wing on the sides.”

Elon said it is “well known that there is not a big gap between Barak and Netanyahu. … In permanent-status talks with the Palestinians about the future of Jerusalem, settlements and Palestinian refugees, the gap is not big between Likud and Labor.”

On the other hand, Elon said, there is a huge gap between him and the Arab parties, and it would be impossible to stretch the coalition so wide that it accommodated both.

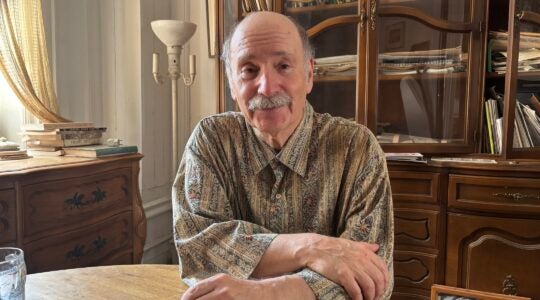

“But this is not the government Barak wants to establish,” Elon said during an interview at The Jewish Week. “He wants a government wide enough that it does not repeat the narrow coalition of [the late Labor Prime Minister Yitzchak] Rabin, who had a minority government of 58 ministers. He was able to have a majority in the Knesset only because of the Arabs; you can’t run a state like this. So if Barak wants to run a state, he has to bring in Likud.”

Elon did not rule out Shas eventually entering the coalition, and a spokesman for One Israel said the door to talks with Shas remained opened. Barak has until July 8 to present his coalition government to the Knesset for approval, otherwise new elections would have to be held.

But the latest turn of events has angered the left-wing Meretz Party, which had been viewed as a natural ally of One Israel. Its leader, Yossi Sarid, complained that “a government with Likud, Shas, United Torah Judaism and the National Religious Party will not bring the change that One Israel and Meretz have promised the voters.”

And Laborite Yossi Beilin, who helped negotiate the Oslo Accords with the Palestinians, groused that Likud’s presence could slow the pace of the peace process.

In an interview in Manhattan before this week’s Likud talks began, Colette Avital, the former Israeli consul general in New York, said a wide coalition was necessary in order to advance the peace process.

“We have to have a wide consensus in the population,” she said. “We have 75 percent of the public’s support for the Oslo Accords, but they have to be brought in and vote on a referendum [on the final status agreement].”

But, Avital pointed out, although the peace process has been put on hold while a new Israeli government is formed, there is still “an inflexible calendar in terms of the peace process” and it must be resumed immediately.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.