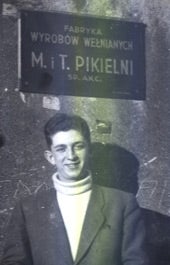

PARIS, Feb. 15 (JTA) — A case before the European Court of Human Rights is being seen as a landmark that could force Poland to compensate Holocaust survivors and their descendants for their material losses. Ongoing attempts to receive compensation from a succession of Polish governments have never succeeded fully, as the country is the only one of the former Soviet satellites with no laws to compensate people for the loss of private property during World War II and the communist era. At a Feb. 9 news conference in Paris, Henryk Pikielny, 76, announced that he had filed the lawsuit at the human-rights court in Strasbourg for “moral, not financial” reasons. The case, the first on Polish restitution to be filed at the European court, was filed shortly before a delegation of American and Israeli Jews arrives in Poland this week to discuss the issue of restitution legislation with officials. The Polish government is expected to present a proposal for compensating Holocaust survivors and their heirs to the country’s Parliament next month. But survivors consider the proposal “unacceptable” because it would provide restitution worth only a fraction of a property’s value, according to Kalman Sultanik, a JTA board member who is leading the delegation. Polish officials would not comment directly on the Pikielny case. “Each case is treated in Poland individually by the proper authorities and courts,” a representative of the Polish Embassy in Washington said. “Where it’s legally possible, property is returned or compensation given.” Those supporting the Pikielny case are not optimistic about the prospects of advances being achieved internally. MIT Pikielny, a textile manufacturer, was founded in Lodz in 1889 by Pikielny’s grandfather, Mojzesz. By 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, the company had 15 buildings, 200 employees and 200 looms. Pikielny’s mother, grandfather and many other relatives died at the hands of the Nazis. Along with his father and brother, Pikielny left for Brazil in 1946. He now lives in Paris. After World War II ended, confiscated property was nationalized and appropriated by Poland’s Communist government, and MIT Pikielny passed through the hands of a series of state-owned entities. Since the country’s democratization in 1990, the company has remained a government holding. After the fall of communism, Pikielny initiated a number of attempts to regain possession of the company. In 2004, he finally was told that he had no chance of ever receiving compensation. Since 1939, Pikielny and his family have seen none of the profits from the company that bears their name. After they exhausted every possible legal channel in Poland, Pikielny said, he and his family began to look to the European Union for alternative courses of action. The case is being brought by a charitable law firm known as the New York Legal Assistance Group, or NYLAG, in conjunction with the Holocaust Compensation Assistance Project, which is funded by the Claims Conference and UJA-Federation of New York. NYLAG has helped more than 50,000 Holocaust survivors navigate the complex and bureaucratic restitution application process. Yisroel Schulman, NYLAG’s director, described Poland’s previous response to restitution demands as “wholly inadequate.” “While many other European countries have acknowledged their role in the Holocaust by enacting legislation or other measures, Poland has yet to address this issue,” Schulman said in the group’s press statement. “For elderly Holocaust survivors who have waited decades for their cases to be fairly heard by the Polish legal system, justice delayed is truly justice denied.” Now that Poland has entered the European Union, it must abide by the E.U.’s human rights laws. Poland is a signatory of the European Convention on Human Rights, which states that it’s a violation of human rights to deny a person “the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions.” Poland thus is legally bound to obey the decisions of the human rights court. Other former Communist bloc countries, including the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania, have made significant restitution to Holocaust survivors and their families, Pikielny said. The Polish government has compensated the majority of those expelled from their homes at the end of the war, but not those who lost property as a result of anti-Jewish measures taken by the Nazis. Given the devastation of the country’s Jews — the 3 million Polish Jews killed in the Holocaust represented about 10 percent of the country’s total population — full compensation could be a heavy financial burden on the country. Poland did strike a deal in 1997 with local and international Jewish organizations to return communal property, such as synagogues. But Jewish communal officials say government bureaucrats have been stonewalling the process through restrictive interpretations of the country’s land-use laws, the Forward reported. Out of a total of 5,544 properties, only 352 have been returned or compensated since 1997, Monika Krawczyk, CEO of the Warsaw-based Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland, told the paper. In March 2001, the Polish Parliament approved a law about restitution of private property for people who were Polish citizens as of Dec. 31, 1999 — a provision that would have excluded most Jews and their heirs — but it was vetoed by the country’s president. Peter Koppenheim, a Polish-born survivor whose family’s former property now is owned by the Thyssen Krupp corporation, said at the Pikielny news conference that “We will not give up until our homes and property are returned.” “We call on new Poland to recognize the survivors’ basic human rights and return their homes and property,” Koppenheim said. According to Jehuda Evron, a survivor who is president of the Holocaust Restitution Committee, a New York-based organization of Polish-American Holocaust survivors, “Poland claims that the survivors and their heirs should go into the Polish court system to secure a return of their homes. Out of thousands of active members of our organization, not a single one has been able to secure the return of the property under the Polish legal system.” Miroslaw Szypowski, president of the Organization of Property Owners in Poland, stressed in a statement that the Pikielny case is important not only in the fight for Holocaust restitution but in terms of a broader fight for the “return of property plundered on the basis of confiscation laws and decrees of the Communist government.” Pikielny’s claim emphasizes this broader context, arguing that “Poland’s continuing failure to clarify the status or property ownership rights within its own borders will have potentially serious moral and economic implications not only for the stability of its own society, but also for the expanded E.U.” There is a precedent for the case. In June 2004, the ECHR ruled that Poland must pay more than $15,000 to a man as reparation for the home his family lost after World War II, when Poland’s borders changed.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.