About three dozen young Jews will meet at a French restaurant in downtown Toronto the first Monday evening in June. Over dinner, for several hours, they will discuss some issues of current Jewish life.

Very few, if any, of the participants in the Jewish salon belong to a synagogue or any other Jewish organization.

According to a survey released this week, these diners are typical of Generation Y Jews –– born between 1980 and 2000 –– in the United States and Canada. And the salon, according to a leader of the group that sponsored the survey, is typical of a small number of independent Jewish initiatives that are attracting these unaffiliated Jews.

“Members of Generation Y have individualized world views, an apparent lack of interest in traditional Jewish institutions, and emphasize diversity,” states the introduction to “OMG! How Generation Y Is Redefining Faith in the iPod Era,” a study commissioned by the New York-based Reboot network. The survey of 1,385 young Jews, Christians and Muslims found that “this age group tends to separate institutional religious attachment from spirituality” –– in other words, many are looking for spiritual meaning, but they’re not eyeing synagogues, churches or mosques.

Reboot included non-Jews in the survey because most Jews in the studied age group have large numbers of non-Jewish friends, and because their feelings about religion and spirituality reflect the wider society, said Roger Bennett, a founder of Reboot who announced the findings at a Washington press conference.

Of all the groups surveyed, Jews ranked near last in the percentage (38) that consider their religion “very important,” trailing Hispanics at 39 percent, blacks at 56 percent and Muslims at 63 percent.

That’s old news. “The basic idea that choice is in the air, and people are doing mix and match in their religious behavior is emerging in every single piece of research,” said Jack Ukeles, president of Ukeles Associates, a policy research and consulting firm with a specialty in the Jewish community.

The Jewish establishment — most synagogues, local federations and other organizations — tends to look at such findings as depressing news, that young Jews are lost to the Jewish community, Bennett said.

He said the findings should create “a sense of opportunity for the Jewish community.” There are a lot of young Jews out there to be reached, he said. “There’s actually a lot that’s right with them. They come across as a generation of seekers. They’re looking for meaning, they’re looking for spirituality.” Often they turn to the arts, or hip young publications, or informal contacts with friends. “In their own way, within their own home, in their own time,” Bennett added.

Members of Generation Y “are in fact extremely interested in religious issues and issues of meaning,” but “have little to or no interest in religious institutions,” Bennett said.

“We have to recognize their hunger for informal interaction,” Bennett said. “That’s a tremendous challenge to synagogues and other organizations. There’s a huge audience.”

The survey was conducted by veteran pollster Anna Greenberg, vice president of Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research.According to the survey, “Generation Y is significantly more likely to say that they have no religious denominational preference or call themselves secular than their elders,” and “among Jewish youth, 60 percent say they would rather express their faith by talking to their friends than by attending synagogue,” also 87 percent of the Jews surveyed are in the “godless” or “undecided” categories. However, researchers pointed out that new Jewish-oriented initiatives such as the New York-based JDub record label or the “socially active” Ikar community in Los Angeles or the Jewish salon in Toronto show that it is possible to bring members of Generation Y into a wider Jewish fold.

“There’s a tremendous power in culture,” separate from the traditional network of religiously oriented Jewish organizations, Bennett said. “We’ve always underestimated the informal, episodic religious experience. We have a tendency to throw up our hands [and say], ‘What’s wrong with these kids?’”

Generation Y has a stronger “anti-institutionalism” bent than Generation X parents or Baby Boomer grandparents, he said.

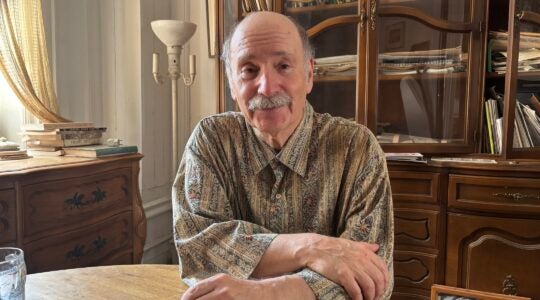

Mireille Silcoff, a journalist and Reboot supporter, started her monthly salon meetings in Toronto a year and a half ago.

“I’ve never belonged to a synagogue. I didn’t intend to join one,” said Silcoff, 32. But she wanted an opportunity to do something Jewish with other Jews.

She hosted the first salon meetings in her apartment. They were by-invitation-only, advertised by word of mouth. Within three months, Silcoff had a waiting list “a mile long,” mostly of 20ish and 30ish artists and media types, and the salon outgrew her home. It moved first to a hotel, then to the French restaurant. “You’re looking at people who would never go to a Jewish thing.”

Participants talk about “Jewish topics” –– the use of counter-culture, the construct of the “cool Jew” –– within “a Jewish context,” Silcoff said. It’s not for meeting dates or making business contacts. The purpose is “to incorporate Jewishness into the everyday life of people.”

“It’s creating community,” she said. “An entire community has been created. All these people are hanging out with each other.” One member started a Torah study class; another, a Jewish art project. “The key,” Silcoff said, “is don’t institutionalize.”

The success of the Toronto salon, versions of which are to start in Los Angles and other U.S. cities, counteracts one of the findings of the survey, that only seven percent of Generation Y members have friends exclusively from their own religious background.

“There are no silver bullets,” the survey cautions. “There are no quick fixes that can solve all of our challenges in one try. Building an approach that offers a range of offerings incorporating a mix of content and formats will be most effective.”

“Do not underestimate the power of culture –– music, DVDs, the written word –– as a mechanism to distribute and convey meaning through personal networks as opposed to institutional membership,” the survey states.

Silcoff said she is not done creating cultural outlets for Jewish members of her generation. She is the editor of the Guilt & Pleasure Quarterly, a journal that will debut in the fall. The quarterly is a natural fit with the salon, she said. “The journal came out of this exchange of ideas.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.