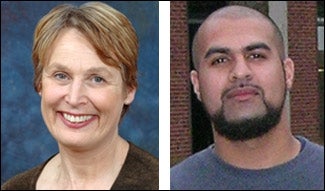

PHILADELPHIA, Aug. 18 (JTA) — While the news from London, Iraq and the Middle East would seem to increase the distance between Muslims and adherents of other religious traditions, there are glimmers of hope. Nearly drowned out by the noise of explosives on subways and car bombs in busy marketplaces, quieter initiatives are under way in which Muslims, Jews and Christians are seeking ways to understand one another and to move their communities toward a better future. We — a rabbi and Muslim doctoral student — have observed firsthand some of these initiatives, and we can report with confidence that the violence of extremists is only one point on a spectrum of views within the Muslim world, a world that is engaging in introspection and internal debate. On college campuses across the country, a petition is circulating among the 600 university chapters of the Muslim Students Association stating Islam’s condemnation of terrorism in all circumstances. Furthermore, Muslim groups realize “condemnation” is not enough. Plans are being made to launch a campaign in which Muslim leaders and scholars address Muslim audiences across the country on what jihad really means and Islam’s emphasis on the sanctity of life. These efforts echo the courageous work of scholars like Judge Hamoud Al-Hitar in Yemen and Allama Javed Ahmed Ghamidi in Pakistan, who, despite threats from extremists, regularly issue fatwas, or legal edicts, against killing civilians and urge Muslims not to respond to oppressive circumstances with oppression of their own. Scholars like these are at the front lines of the struggle to honor tradition while adjusting to contemporary times. As academics we sometimes travel abroad to participate in events that do not necessarily make the evening news but are significant nonetheless in promoting the cause of understanding. Nancy, for example, recently returned from Qatar, where, at the invitation of the Emir, she attended an international conference of Muslims, Christians and Jews. She was one of four American rabbis along with one French Jewish layperson who addressed the conference. It was the first time Jews had been asked to participate in the conference. She was able to hear firsthand the true “clash of civilizations,” which is not just between Islam and the West but also between different factions within Islam struggling for hegemony. The culture of hate and absence of self-criticism were topics that were hotly debated among the Muslims attendees. When a Muslim speaker excoriated both Christians and Jews and spoke about the “Zionized West,” the Muslim conference moderator took the authority of the chair to comment, “We must be frank. I would have hoped your talk could have included some criticism of Islam as well.” Another Muslim speaker, professor Al-Ansari of Qatar University, said, “If the Palestinian problem is solved, will all our problems be over? No. Muslims show hatred and opposition also among themselves.” In these exchanges we also could hear echoes of the internal conflict that continues within the Jewish world between some religious extremists bent on keeping the “whole land of Israel” and other Jews working for a humane, pragmatic and, in the best sense of the word, “holy” solution to conflict. Adnan recently traveled to the Maldives with a group from the University of Pennsylvania Law School that is helping the government there craft one of the first modern penal codes in the Muslim world. This project seeks to blend shariah, or Islamic law, Maldivian culture, and contemporary theories on criminal codes to foster the development of a comprehensive modern criminal justice system. Closer to home, the two of us are creating a course to be taught this spring in Philadelphia at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, with support from the Middle East Center at the University of Pennsylvania. The course will give Jewish and Christian seminary students the opportunity to become knowledgeable about Islam, particularly the history of the last 100 years, so that they can be agents of understanding and cooperation as religious leaders in the communities they will serve. The course, which is unique and desperately needed, will be taught in a service-learning model. We intend to educate the students about the issues, while supervising them as they work alongside Muslim graduate students from the University of Pennsylvania who will go into the Muslim, Jewish and Christian communities to educate young people and their teachers. In addition to increasing understanding among the different parties, we hope our course will help people resist the temptation to oversimplify complex issues. Understanding among Muslims, Jews and Christians is needed so that serious conversation can follow. We expect that all these developments will have a cumulative, positive bearing on the world situation. They are admittedly small steps. But we pray that they will help spawn similar initiatives and create a world in which the headlines we see will bring us better news. Rabbi Nancy Fuchs-Kreimer is an associate professor of religious studies at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in Wyncote, Pa. Adnan Ahmad Zulfiqar is a student at the University of Pennsylvania. He is completing a doctorate in Islamic jurisprudence and a law degree at the law school. He is an adjunct professor at Arcadia University and the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.