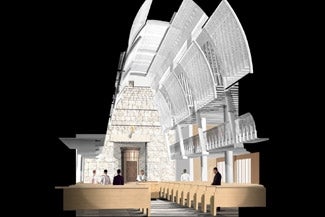

ANNAPOLIS, Md., Aug. 29 (JTA) — Harvey Stein had a dream: Provide Jews at the United States Naval Academy with their own worship space. Nine years and almost $9 million later, his dream will become a reality, with the opening of the Uriah P. Levy Center and Jewish Chapel. The academy estimates that some 1.5 million visitors will tour the facility during its first year, and is scheduled to open the weekend of Sept. 16-18. This high visibility is a prospect that pleases Stein no end. “This will become one of the most important Jewish buildings in the country,” said Stein, 69, the owner of a successful home-decor and personal accessories business. “Lives will be touched in ways that we will probably never fully know.” Said Rabbi Irving Elson, the academy’s Jewish chaplain: “This is not just a building for Jews. It’s the next step for the academy in demonstrating how important faith is, any faith,” adding, “It’s a symbol of tolerance and inclusion and for understanding how important faith is in the toolbox of our future Navy and Marines officers. I want our officers to recognize that even if they don’t have a faith themselves, that faith is important to the men and women they command.” A full weekend of events is planned for the building’s opening, beginning with the affixing of mezuzot and the dedication of a Torah scroll donated by the Israeli navy, and ending with a formal dedication attended by at least 2,500 guests. The Naval Academy, which educates officers for the Marine Corps as well as the Navy, is the last of America’s three main military academies to construct a worship space designed specifically for Jews. Until now, Jewish midshipmen shared a chapel with other minority religious groups. The academy has a separate chapel for Christians. All U.S. military worship facilities are called chapels, regardless of faith. The lack of a Jewish facility bothered Stein, one of a number of Annapolis Jews with no Navy or academy ties who come to the academy to attend regular Friday night services run by Jewish chaplains; Saturday services are only held on holidays and special occasions. One morning in 1996, while speaking in his kitchen with Rabbi Jonathan Panitz, then the academy’s Jewish chaplain, Stein announced that he wanted to help underwrite a Jewish chapel. Stein said the sound of the words popping out of his mouth took even him by surprise. “When I said that to Jonathan, I thought: ‘Whatever possessed me to say such a thing?'” Stein recalled. Panitz seized upon the idea immediately. “I said, ‘OK, Harvey, when do you want to start?’ And Harvey says, ‘Right away.’ And that was how it began,” said Panitz, now retired from the Navy and leading Congregation Beth Israel, a Conservative synagogue in Lebanon, Pa. The pair turned to Friends of the Jewish Chapel, a group that helped fund activities for Jewish midshipmen, including trips to Israel. But with less than 150 self-identified Jewish midshipmen in any given year, out of a student body of more than 4,000, getting permission proved tricky, despite lobbying that extended to the highest reaches of the Pentagon. The key to jump-starting the project was a pledge by the group to expand Stein’s idea to include raising additional funds to meet other unfulfilled academy construction needs. That led to creation of the Uriah P. Levy Center, which occupies the 35,000-square-foot structure’s south wing. It’s named after the first Jew to be elevated, in 1858, to the rank of commodore, then the Navy’s highest rank. Levy, who restored Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia home, Monticello, after it fell into disrepair following the third president’s death, was descended from some of the first Sephardic Jews to settle in the American colonies. Howard Pinsky, a 1962 academy graduate and the president of the Jewish chapel group, said about $8.75 million has been raised for construction. Another $3 million was raised for maintenance and program endowment funds. Most of the money has come from private Jewish sources. The center will house the academy’s expanding courses in ethics and leadership and its Honor Court, where midshipmen charged with violating the academy’s strict honor code are judged by peers. It will also contain a library dedicated to religious and ethical themes; study, lounge and canteen areas, and displays relating to Jews in the American military and other subjects. The chapel takes up the three-story facility’s entire north wing. The interior of the 410-seat sanctuary is extensively faced with Jerusalem stone. The floor-to-ceiling section behind a free-standing Sephardic-style ark has been hand-crafted to evoke the Western Wall’s jumble of stones. Both the center and chapel have Stars of David incorporated into their exterior design. Architect Joseph Boggs said he believes this is the first instance of the Jewish symbol being a permanent part of a U.S. Navy building. (An academy spokeswoman could not confirm the claim because of the sheer number of Navy buildings worldwide.) The complex occupies a prominent spot on the 330-acre academy. Enclosed passages link the building to Bancroft Hall, the massive dormitory housing all midshipmen, and to Mitscher Hall, the academy’s primary building for social and cultural activities. Boggs said he sought to design the structure so as not to overwhelm non-Jews. “How do you incorporate inclusion without any negative implications? I want any midshipman of any denomination to be able to walk through this place and not just be comfortable, but get a chill down their spine,” said Boggs, who is not Jewish.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.