BARCELONA, Dec. 14 (JTA) — Barcelona is restoring its old Jewish quarter, but the local Jewish community says it’s being shut out of the process.

In the Middle Ages, Barcelona’s Jewish community of 4,000 people played an integral role in the city. Acting as a bridge to immigrants from throughout the Mediterranean, the local Jews spoke Greek, Hebrew, Spanish, Catalan, Latin and Arabic.

But in 1391, anti-Jewish riots moved up the Iberian Peninsula. A large number of Barcelona’s Jews were forced out, killed or converted.

Six hundred years later, the city is in the process of restoring its old Jewish quarter, known as the Call, renovating 21 buildings and creating an interpretive center. Similar projects have been carried out in other Spanish cities such as nearby Gerona, where Jewish life also flourished.

These programs are part of a government initiative to restore ancient Jewish neighborhoods throughout the country and present them as tourist attractions.

What distinguishes the Barcelona initiative is the presence there of a modern Jewish community numbering about 5,000.

Representatives of the city’s Orthodox, Reform and Chabad communities say they are being ignored in the initiative.

“We very much appreciate that City Hall is finally getting involved in restoring its Jewish past,” Tobi Burdman, president of the Israelite Community of Barcelona, told JTA. “What we don’t want to see is a Jewish quarter without Jews, in the style of Gerona. Here there’s a living Jewry, one that should be listened to and consulted with, and not just called up to appear in the photo.”

Adding to the community’s resentment has been the issue of Montjuic, or “Mountain of the Jews,” in Catalan. Known for its massive sports stadium, which hosted the 1992 Olympic Games, Montjuic also is the location of one of the oldest and largest Jewish cemeteries in Europe, which was used from the ninth to the 14th centuries.

In 2001, more than 500 tombs were discovered during construction on the mountain, but still there are no monuments commemorating its historic importance.

A meeting in late November between urban planners and community members addressed Jewish concerns about construction plans that would affect the area where the cemetery lies. Community members at the meeting said some progress had been made in terms of protecting the site and eventually placing a monument there.

This follows a drawn-out struggle by community representatives to denote the cemetery area as a landmark and prevent future city plans to build bars, bathrooms and other facilities directly over the ancient cemetery.

One community spokesman said there seemed to be a slight difference in attitude among city planners dealing with Montjuic and those in charge of the restoration of Call, who he said had been “completely unreceptive.”

Regarding the old Jewish quarter, Teresa Serra, a City Hall official dealing with the project, told JTA that the city is restoring the quarter as it would any other historic area in Barcelona.

“The only difference is that there will be a center of cultural reference for the neighborhood involving everything from the Jewish epoch,” Serra said. “So there, yes, they could participate. Not in the architectural part, because they’re not involved in the construction phase,” but perhaps in providing cultural information about Sephardic kitchen use or Jewish holidays.

Told that it’s a sensitive issue for the community given its tragic history, Serra responded, “You have to understand, this is not a very major issue for the city.”

Community members say they would like to play at least some role, even something as minor as reviewing texts, brochures or museum signs. But Serra said the city has yet to receive a clear proposal for participation from the community.

Some community members insist they’ve asked repeatedly to meet with city officials to discuss drafting a proposal. But community sources have acknowledged past divisiveness and said the community is just beginning to make its voice heard in a unified fashion.

Many Barcelona Jews have initiated efforts to restore the quarter, notably Miguel Iaffa.

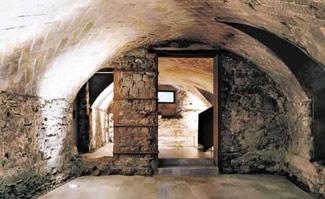

Inspired by the findings of a medieval historian that pointed to the location of the quarter’s main synagogue before the 1391 pogrom, Iaffa purchased a portion of the site in 1996 and restored it, preventing the space from being turned into a pub.

“That the city is now trying to reap the benefits of our efforts to recover the neighborhood seems perfectly fine with me,” Iaffa said. “But they’re doing it with a sectarian spirit and without greatness. What they’re interested in is having American Jews come and do tourism and spend money like they do in Gerona. They’re not interested in us at all.”

David Stoleru, an architect and active community member, managed in 1997 to prevent the city from tearing down the “house of the rabbi,” a building that is believed to have been a school of Jewish studies.

When the Jewish community presses City Hall on the subject, “they totally move away from us and they have never, in spite of our will, accepted our inclusion in the program of carrying out these projects,” Stoleru told JTA.

Dominique Tomasov, also an architect and a founding member of the Reform congregation, independently began giving a Jewish voice to guided tours of the neighborhood in the late 1990s.She tells visitors the history of Barcelona Jews while tying it in to the re-emergence of a living community.

Tomasov spoke of fruitless efforts to build some sort of partnership with the city around the renovation project.

“What upsets me most about this is that Judaism is a living culture,” she said. “It has a presence in Barcelona, and we could bring Jewish authenticity to the project.”

Various sources, including those in City Hall, said anti-Israel feeling has affected the city’s attitude on some level.

Serra admitted that biases regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had to some degree “contaminated the atmosphere” around the renovation project.

“There is an anti-Semitic attitude here because of this problem of anti-Israelism that influences everything,” Pilar Rahola, a former legislator from the Catalan Left Party who initially brought city funding to Iaffa’s synagogue project, told JTA. “With respect to City Hall, the government of Barcelona, like the government of Spain, prefers ‘Jewish stones’ to living Jewish people.”

Rahola, who is not Jewish, added that while the rest of Spain is at least interested in uncovering its Jewish past, this is not the case in Barcelona.

“There’s no desire to even recuperate the medieval past,” she said. “We’re faced with an administration that has a strong allergy to the Jewish topic, even though it might not clearly practice anti-Semitism.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.