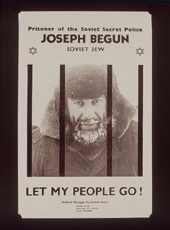

TEL AVIV (JTA) – Back when he was toiling in the snow of the Ural Mountains and elsewhere during 16 years in the Soviet Gulag, Yosef Begun did not imagine his future home as a place with rockets falling and leaders in crisis.

Punished by the Soviet authorities for his underground activities as a Jewish activist, Begun knew Israel was an embattled country, but he had high hopes for its future.

“I think like every citizen in Israel, I see the situation getting worse,” he says, during a recent interview in Jerusalem. “The Kassams falling? We did not have those in mind when we immigrated from Moscow.”

The focus of Jewish activists like Begun was how Israel emerged victorious in battles like the 1967 Six-Day War and even the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

“But what do we have now? We have no leaders today,” Begun says, adding later that “leaders reflect the people who select them, so there is something off with the people of Israel choosing such leaders.”

Begun, 75 and living in Jerusalem, is a grandfather. H his eldest granddaughter is serving in the Israeli army. He works as a publisher, mostly putting out books with Jewish, Israeli or Zionist content in Russian. He takes those books to the former Soviet Union.

Citing the vanishing number of educated Jews there, he says, “There is a great need for books.”

Begun, who recently led a Moscow tour of “refusenik” sites for American Jewish activists, says he still sees himself as the impassioned Zionist, but he is disheartened by the mood when he returns home from his trips to the former Soviet Union.

“There are people who want a Jewish life and Zionism, but most of the nation seems uninterested in such things,” he says. “The country seems tired.”

Begun often thinks back to the long, hard years of imprisonment and struggle. Even now he is struck by the Soviet regime’s success in stopping Jewish life. He feels a personal mission to make up for this lost time.

The memoir Begun is writing now opens with him as a small child asking his mother what the word “Jewish” means. His playmates had teased him for being a Jew.

“I cried and asked, ‘why am I a Jew?’ ” Begun recalls. “I did not want to be.”

Despite his early identity conflict, he eventually became a Hebrew teacher and activist in the refusenik movement. Like others, Begun believes the incredible showing of Jewish unity paved the way to a successful outcome in the Soviet Jewry struggle.

“Everyone – Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, religious, not religious – they were all together,” Begun says. “It shows how when everyone unites, there can be success.”

Looking at the situation of the immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel now, he sees a picture of overall success – their contribution to the economy, their finding a place in Israeli society.

One of his main complaints, however, is the Orthodox religious establishment and its conversion policies. They have been seen as especially stringent – demanding in some cases, for example, that converts send their children to Orthodox schools and families prove their synagogue attendance.

“It’s not OK that the rabbis make such difficulties,” Begun says. “These are people who are insensitive and don’t realize that these immigrants want to be part of this nation. Instead they say they are not good Jews. It’s nonsense.

“We need as many people to be part of our community as possible. If you ask who is a Jew, it’s a Jew who is already a Jew in his or her heart.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.